An eyeball peers out at you from the crack in a door. Disembodied hands extend from the endless darkness of an abandoned alleyway. A reflection, not your own, stares at you from outside of a dirty train window. These are the kinds of images that populate the pages of Masaaki Nakayama’s works (Fuan No Tane, PTSD Radio).

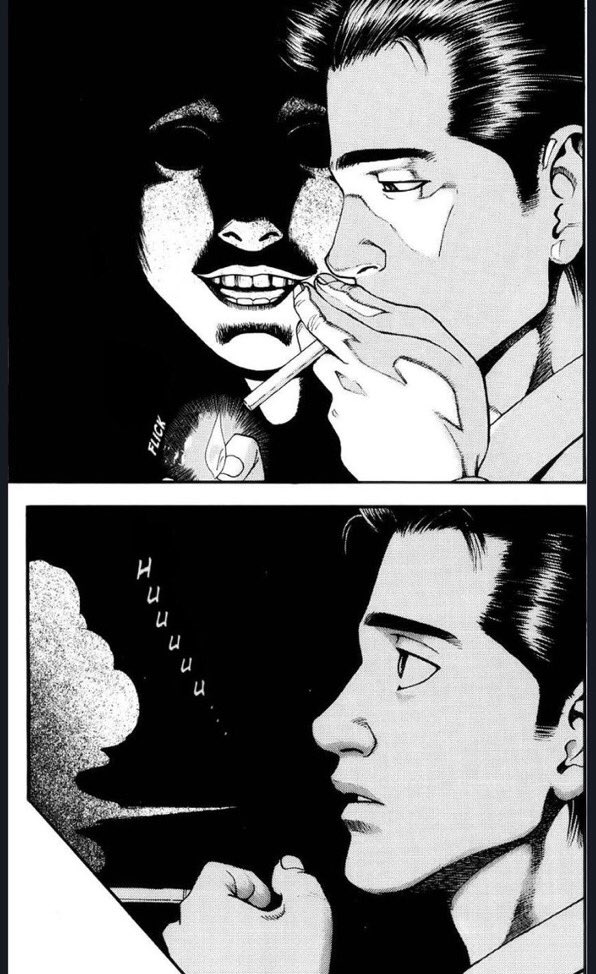

Known for his short, often disjointed and fractured storylines, Nakayama is a creator obsessed by the plane of existence between ours and the next. That is to say, horrors that we as humans can just barely grasp, horrors that are so subtle, so close to our world, that we might not even notice them (one notable example of this is a story in which a man smokes a cigarette in the woods, completely unaware that he is being watched by a shadowy figure who lurks just shy of his peripheral vision). Many of Nakayama’s stories are only a few pages long, giving the reader a glimpse into some kind of otherworldly terror, but never giving any details. Nakayama often utilizes the short, uncertain nature of his works to insert an air of creepiness into them.

While the word “creepy” is often used to describe unsettling or upsetting visuals/feelings, it is rarely studied from a scientific or factual perspective. How exactly do you define creepiness? Is it a haunted mansion? A hitchhiker? Or a bump in the night? What qualifies as creepy will inherently differ from person to person, but there is one definition that can be applied directly to Nakayama’s manga. In a 2016 study held by The Department of Psychology at Knox College in Galesburg Illinois, American psychologist Francis T. McAndrew described creepiness as the ambiguity of threat. His paper, titled On the Nature of Creepiness, presents the belief that creepiness is “-an evolved adaptive emotional response to ambiguity about the presence of a threat that enables us to remain vigilant during times of uncertainty” (McAndrew, 2016). McAndrew further details this belief by comparing so-called creepy occurrences to those that are terrifying or horrifying. “A mugger who points a gun in your face and demands money is certainly threatening and terrifying. Yet most people would probably not use the term ‘creepy’ to describe the situation. It is our belief that creepiness is anxiety aroused by the ambiguity of whether there is something to fear or not and/or by the ambiguity of the precise nature of the threat (e.g., sexual, physical violence, contamination, etc) that might be present” (McAndrew, 2016).

With this idea in mind, it becomes easier to classify something as creepy. A sound coming from a dark alleyway, the creaking of floorboards in the night, a figure in the distance. Is it the sound of a raccoon rummaging through trash, or the sound of a man waiting to take hold of you? The house settling, or an intruder? Someone waiting for the bus, or someone watching you? In situations like these, there is no way to know what a threat might be, or if there even is a threat in the first place. Human beings, however, typically err on the side of caution, making the assumption of danger instead of the assumption of benevolence. “If you are walking down a dark city street and hear the sound of something moving in the dark alley to your right, you will respond with a heightened level of arousal and sharply focused attention and behave as if there is a willful ‘agent’ present who is about to do you harm. If it turns out that it is just a gust of wind or a stray cat, you have lost little by over-reacting, but if you fail to activate the alarm response when there is in fact a threat present, the cost of your miscalculation may be quite high” (McAndrew, 2016) Therefore, creepiness is the ambiguity of threat combined with the human tendency to assume danger in such uncertain scenarios. This definition can be applied directly to the many works of Nakayama.

Both Fuan no Tane and PTSD Radio utilize the ambiguity of threat to create tension and unease. One story from PTSD Radio, titled 57.31NHz (each chapter is named after a frequency of the titular radio program), sees a young woman stopped in her tracks when a spectral figure appears on the train tracks in front of her. She initially fears that the figure may be attempting to commit suicide, but grows confused when the train passes right through it. The other subway goers are unable to see the figure, and thus enter the train without worry. Unbeknownst to them, they are riding with a creature from another world. There is no aggression, no violent action, no sign of malicious intent, only a dark specter standing idle amongst the crowd. The young woman makes the decision not to board the train and wonders what will happen to those who did.

This, more so than any other chapter in PTSD Radio Volume One, embodies the aura of creepiness as defined by McAndrews. Is this phantom dangerous? Does it want to hurt the people on the train, or is it just hitching a ride? The young woman, as well as the reader, will never know. The story ends before any of these details can be fleshed out, giving us just enough to comprehend the possibility of danger, but not enough to come to any definitive conclusion.

While there are many other works that use ambiguity to create fear, it is rare that the fear it creates can be called “creepy”. Compare Nakayama to the works of the masterful Ito Junji, for example. Most of Junji’s stories are not fully explained, (what is the origin of the curse in Uzumaki? Where did the Hanging Balloons come from? What will become of The Long Dream?) but the threats typically remain identifiable. The Fashion Model wants to eviscerate you, the Gyo will eat you alive, Tomie will drive you mad, Frankenstein will rip you limb from limb. The tangible nature of the threats (that is, knowing that it is a threat) is what removes Ito Junji’s work (for the most part) from the realm of creepiness as described by McAndrews. What makes Nakayama’s use of creepiness so effective, beyond the striking imagery, is the way that he relates it to real-life issues/phenomena.

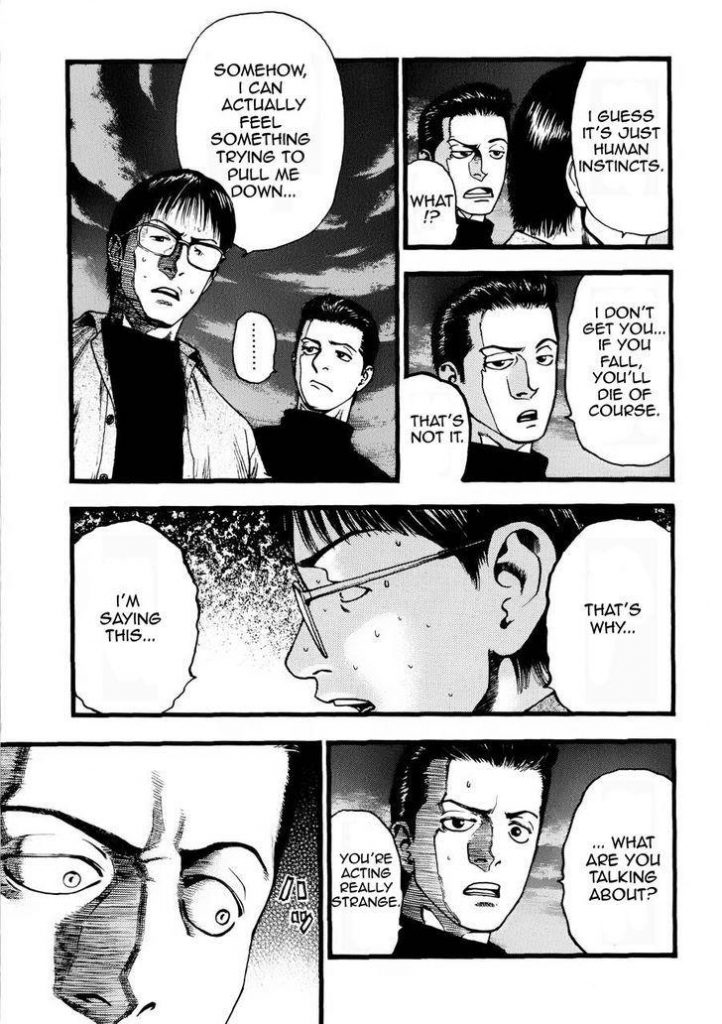

In 64.98NHz, two men on a rooftop contemplate L’Appel Du Vide, or, the call of the void, a phenomenon that causes people to have the strong, impulsive desire to commit violence upon themselves or others. Ultimately, the call of the void is mostly just a feeling that is never acted upon, but its presence is often unnerving and upsetting. One of the men on the roof believes that this feeling is brought on by invisible forces, beckoning human beings towards and over large drops. His hypothesis is proven correct when ghostly hands reach out towards both of them from the drop below.

While the call of the void may not truly be due to ghostly figures, it is still fascinating to present the possibility that strange reactions and feelings are a result of an otherworldly presence. This possibility is one that has been a part of culture and folklore for longer than most people know. Sleep paralysis has been explained in the past as being the weight of a hag who sits on top of sleeping humans as she curses them. Mental illness (particularly as seen within women) was demonized as witchcraft and targeted as a sign of evil. Sexual deviance was a symptom of the seduction of Succubi.

Nakayama uses the uncertainty of phenomena to insert a line between humans and the ethereal plane that lurks just beyond the surface of their perception. In 68.59NHz, a woman finds herself trapped on a staircase as dark hands reach out to her, perhaps to pull her into the beyond. A mother and father contemplate the possibility that these horrors are a result of past evils leaving behind their presence, which manifests in strange happenings and phenomena (an idea that has been explored frequently in works like Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves and Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House). Nearby, their children study an ancient statue, which has been connected in previous chapters to ancient rituals and long-lasting spiritual charms. The statue first found its usage decades ago, as people either prayed to it for the safe travel of their loved ones into the afterlife or spit vitriolic curses into it in the hopes that it would drag evil souls to hell. In the modern day, however, the statue is just an old thing, and neither the children nor the parents have any reason to suspect a connection between it and the odd occurrences near their home. Even the reader, who has a slight understanding of the statue, cannot fully comprehend the impact that it has on the modern world, as the full details of its history and power are never completely explained. We are given just enough to know that something about the statue is off, that it may be having adverse effects on the world, but are never told exactly what it does or how it does it. It exists in the realm between, not directly dangerous, but not devoid of malice either. It is perfectly in line with McAndrew’s definition of creepiness.

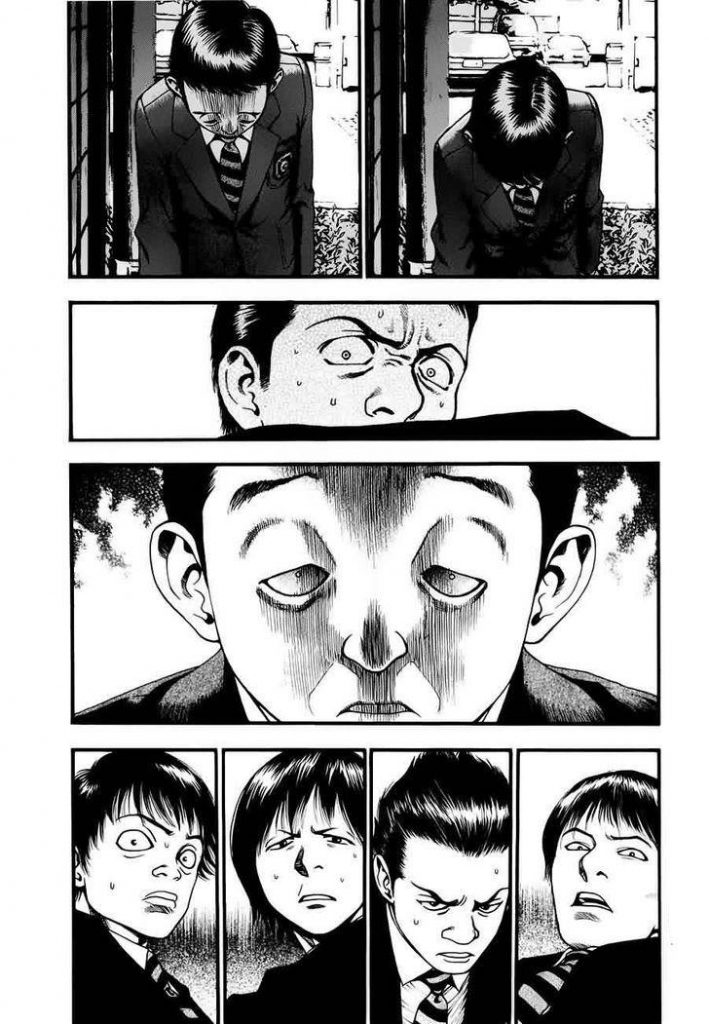

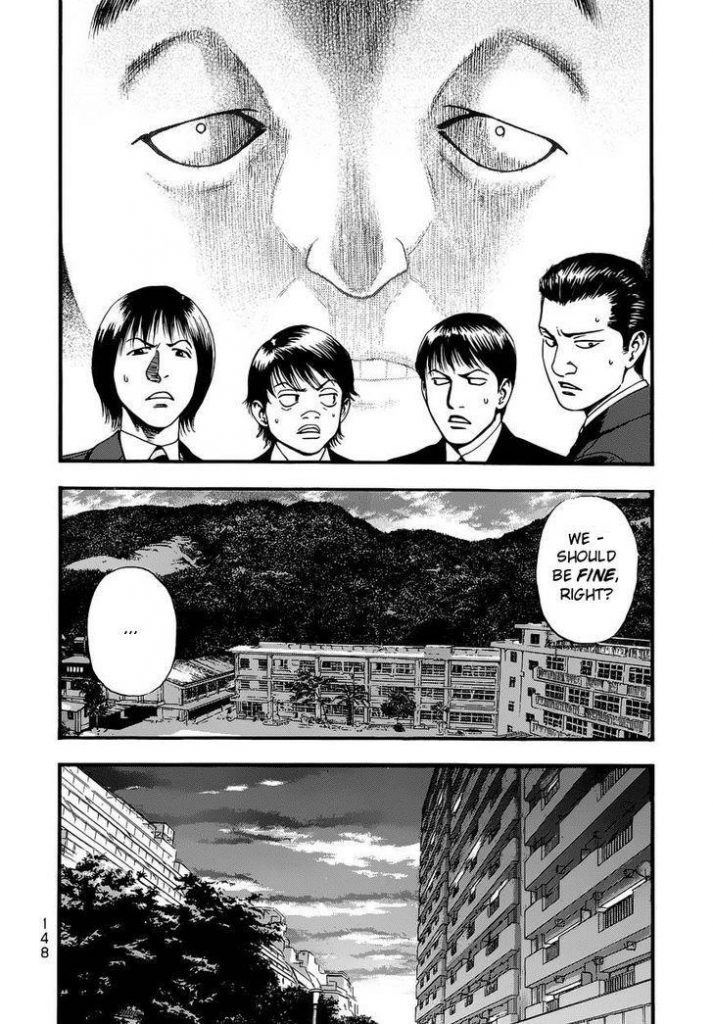

Nakayama does not draw the line at the psychological, however, as he also turns his aura of creepiness onto social happenings as well, casting a looming darkness over our lives and decisions. In 18.41NHz, a young boy is bullied by his fellow students, who plan to shave his head bald if he is not willing to pay them what he owes. In response, the younger student slams his hand into the ground, fracturing his fingers and leaving his assailants at a loss for words. The leader of the bully group is left shell-shocked, and, after being ridiculed by his peers for being afraid, finds himself unable to move from the very place where he watched the boy maim himself. Shadowy figures (a common mainstay in Nakayama’s works, if you couldn’t tell already) begin to approach him at sunset, and he begs for them to leave him alone as the story ends without a satisfactory conclusion.

It is unclear if Nakayama intended this, but the rageful outburst of the bullied student is reminiscent of real-life self-harm. The bully is kept locked in place, perhaps tied to the harmful acts that he has played a part in. Are these shadows representations of the pain he has put out into the world coming back to bite him? Showcases of the destruction that he has caused? The regret? The consequences? 18.50 NHz showcases this fear, as the other bullies talk to each other about their former leader, and how he was found crumpled up, unable to move in the very same place he was the day before. They question whether or not they will be okay, unsure if what they have done in the past will lead to unsavory results. Unbeknownst to them, the bullied student prays to the aforementioned ancient statue, preparing to take revenge on those who have wronged him. The cycle of wrongdoing and uncertainty continues to create nothing but confusion, regret, and revenge.

In these chapters, the uncertainty comes less from the actual specters themselves, and more so from the possibility that they exist due to the actions of their victims. How will our actions foretell the future? What will the consequences be? When we act, we do so without an accurate understanding of what will happen next. We take chances. Asking someone out on a date, auditioning for a school play, rejecting someone, choosing to yell instead of speaking calmly. Every action taken can create the uncertainty of threat, which gives a universality to the horror that Nakayama presents. While his works may be short, they leave nothing to be desired in regard to quality, contemplation, and of course, creepiness.

One more thing, and I hope you don’t mind me asking, but I just couldn’t help but notice, and it’s been distracting me this whole time.

What’s that behind you?

Works Referenced:

McAndrew, F. T., & Koehnke, S. S. (2016). On the nature of Creepiness. Elsevier, 1–6.

Kelly, M. B. (2018, June 29). The science behind the ‘call of the void’. Endless Thread. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.wbur.org/endlessthread/2018/06/29/the-call-of-the-void

Grover, S., Mehra, A., & Dua, D. (2018). Unusual cases of succubus: A cultural phenomenon manifesting as part of psychopathology. Industrial psychiatry journal. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6198602/

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply