In 2017, Jake Halpern and Michael Sloan produced a biweekly comic series for The New York Times which followed the Aldabaans, a Syrian refugee family who had arrived in the US on the day of the 2016 presidential election. Halpern and Sloan later received the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for their editorial cartooning in Welcome to the New World. Preserving its ambiguously eerie title, those twenty-two single panel graphics have burgeoned into a full graphic story that now feels much less anecdotal. The finished product is the result of not only years of interviewing and reporting, but also a flowering friendship with the Aldabaan family. As a work of comics journalism, it was also an unusually collaborative endeavor, even as the authors habitually “resisted the temptation to take anyone’s account at face value.” Relying upon charmingly simple linework and the single color palette of Halpern’s iconic “Blue Style”, the narrative delivers a moving story about losing one’s home, again and again, while still hoping to find a new one.

The book begins with the family in Jordan, as Ibrahim Aldabaan ponders whether he should move his family to the States. Two of his brothers have not yet received their immigration permits, and his mother (whom the children call Yumma) refuses to leave Jordan if it means leaving anyone behind. Naji, Ibrahim’s son, pushes the most for departure: “If we stay in Jordan, what are we going to do? I can’t go to school. You can’t work. So either we’re gonna be homeless or you’ll have to work illegally and then you’ll get caught… What if you get sent back to Syria? Huh?” The Aldabaans are all too cognizant of their depleting savings, and, as the possibility looms larger that Trump may become president, Ibrahim and his brother Issa decide that, given the chance, their families must go. Halpern and Sloan discerningly relay the numerous anxieties of migration: neighbors who threaten to impede their travel as a means of extortion, the possibility that they will have sold everything only to be turned away by airport security for unknown reasons, not knowing where to go upon landing in a foreign airport, worrying over the immense bulk of luggage, having to utterly depend upon strangers to be sponsors. The next day, Ibrahim receives a mournful text message from his mother: “Now that Trump is president, I am not sure that I will make it to America or see you again soon. I hope that I will live a long life.”

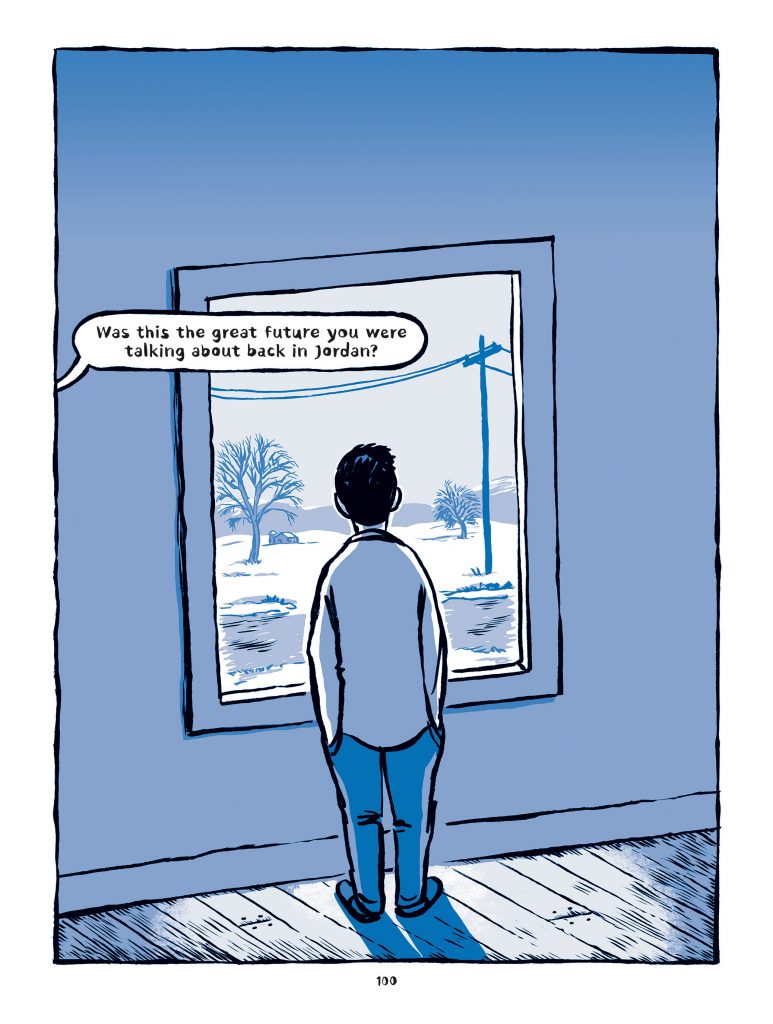

As the Aldabaans familiarize themselves with Hartford, Connecticut, they find themselves feeling isolated, belittled, helpless, and somewhat disappointed with the promise of America. Even more, they are informed by IRIS, the refugee resettlement agency, that they will have to become financially independent within four months. Their co-sponsors are aware of the infeasibility of these terms for the recent refugee: “They’re unemployed. Don’t have a driver’s license. No social security number. No medical history. Don’t speak much English… Don’t even really know where they are. And what, in ninety days, we’re supposed to walk away and say good luck?” As Ibrahim and Issa struggle to find employment, their children must learn to adapt to an American school setting. Naji is surprised by his own misconceptions: “No one’s bumping my shoulder or knocking my book bag, like in Diary of a Wimpy Kid. It’s more like… they don’t even see me.”

So too does Naji’s father feel shocked when his co-workers are unaware of the ongoing civil war in Syria: “Never heard of it… Like it never even happened. Just focus on the dishes. Keep scrubbing, Ibrahim. Keep scrubbing.” The authors linger upon these small gestures of exclusion to highlight how the Aldabaans are continually made to feel out of place. To notice only hyperbolic instances of bullying and racism would be to overlook its more nuanced and systemic manifestations, such as the brutally short resettlement period which their co-sponsors would justify with a xenophobic distinction: “But they’re survivors. Right?” Heinous acts of hatred do occur, such as when Ibrahim receives a threatening phone call and feels compelled to move his family into a motel for the time being, even as they cannot afford to do so. But the narrative links even these acts back to daily gestures from their neighbors—Ibrahim’s wife Adeebah wonders whether the phone call had come from that truck driver who had glared at her so vilely. She tells Ibrahim: “Ever since we left Syria we’ve been running. I’ve never felt safe.”

At this midpoint, the narrative shifts back to Syria in 2011 where anti-government protests are mounting against President Assad and his cronies. These panels are inked in a haunting grayscale which makes the previous Blue Style come to seem less gloomy than it was. The Aldabaans remain cautiously detached from the ongoing political movement, as they fearfully remembered the 1982 Hama Massacre. But in the backlash against these protests (now called the “Siege of Homs”), Ibrahim and his brothers are arrested and tortured without explanation. When Adeebah visits him in prison, Ibrahim tells her not to waste her time alongside the crowds of women in the courthouse who are petitioning for their husbands’ release: “If I do get out, I could just get arrested again. I may be safer in here.” The character design in the story is so minimalist that the few characters whose faces do not conform to the boilerplate model immediately stand out from the rest. Only three such faces recur in the book: the aged and wrinkled face of their Yumma, the blubbery face of Donald Trump, and the pitifully decrepit face of Ibrahim while he languishes in prison. Meanwhile, Naji and other boys daily put themselves in danger while trying to scavenge for food and salvage raw materials which can be sold to merchants.

Through the course of Welcome to the New World, Naji and his father regularly take heat from everyone else when the American Dream falls short. Ibrahim tells his brother over the phone: “Everyone is cooped up. Frustrated. And they blame me. I get it. I’m the baba. I brought us here. Meanwhile, Ma blames us for leaving Jordan… I’m getting it from both sides.” They are forced to recalibrate their expectations of what is possible in America. Issa’s wife urges him against doing manual labor: “I thought we talked about this! What about your back? Issa, you can’t manage… We came here so you could get treated, get better.” Issa responds with a more sobering attitude of self-sacrifice: “We came here for the kids.” As anti-Muslim attacks escalate under the Trump administration, the Aldabaans begin to wonder whether they might need to move to Canada for their own safety. The American Dream feels unfulfilled, but the story of the Aldabaans does not deflate this dream in its typical fashion. They do not regret coming to America because they cannot regret a decision they had no choice over. The black and white panels which depict their memories of Syria and Jordan are decisive in revealing their movements as forced migration. They had to abandon their home in Syria before Ibrahim would be arbitrarily recaptured, and they had to leave Jordan because they were denied refugee work permits. In the States, they know that Yumma is dependent upon their remittances for her medicine, even while she may blame them for being away.

When a landlord watches the Aldabaans struggling, he thinks to himself, “They’ve just arrived—left their homeland. Sounds familiar.” The panels abruptly shift back to grayscale as the landlord recalls Vietnamese refugee tenants who were still arriving in 1990, many years after the official end of the war. This work shares moments in which ordinary Americans are doing their best to lend a helping hand to refugee families such as the Aldabaans. But the story also depicts a much more sinister version of the American Dream, in which refugees fleeing from American-manufactured militaristic crises must bitterly concede to their reliance upon American charity. The way in which the Aldabaans comfort each other with the thought that they will soon be able to return to Syria together functions as a refrain throughout the narrative. In the final pages, Adeebah stares at their Syrian house key which she had kept with her all this time. Ibrahim shows his wife a video of strangers moving into their former home but says, “Before I even saw the video, I knew in my heart that the house was gone.”

In Welcome to the New World, this sense of loss and being in limbo encompasses the emotional turmoil of the Aldabaans. As much as they care for one another, the family also fragments under the pressure of their past trauma and present loneliness in American society. They learn to get by: Ibrahim focuses on his work and silently endures the anger which his family directs toward him; Adeebah turns toward artwork and tries to be patient with her husband; Naji and his sister Hala grapple with their own adolescent identities, especially as it pertains to race and gender. The black and white panels remind us of the other refugee families who are still living precariously and untenably in Syria or neighboring countries such as Jordan. Yet, this is neither a story of refugee gratitude. While Halpern occasionally uses entertaining visual layouts such as a board game, calendar, or playing cards in order to highlight the game-like and procedural nature of assimilating into America, his abiding Blue Style ultimately accords with an overarching tone of melancholy realism. On the day before leaving Jordan, Naji gets his hair cut. Ibrahim, noticing his son’s excitement, comments, “It’s like your wedding day, isn’t it? And America is your bride.” America is not the bride the Aldabaans had collectively hoped for—but they find ways of living with this new member of their family.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply