“Why is everyone so sad?” my sister asked me as I was giving her a tour around the art school I was studying at. I was confused. I didn’t notice anyone sad. Studying on that campus had always been a dream come true. Everyone there had been selected from a large range of applications – there was no room to be “sad”, it was an amazing opportunity. Yet, I immediately got her point.

As we walked through the College of Fine Arts, we encountered some colleagues of mine who took the opportunity of our passing by to let some steam off. Of the dozens of people we talked to, few had anything to say other than to complain about the stress, the pressure, and the letdown they felt from that environment – but I thought it was normal, studying at any university is supposed to feel overwhelming, right? But my sister went on. She mumbled, disappointed: “I thought this would be like Fame or something”.

In 2011, I got into the most prestigious art school in my country right after finishing high school, a choice that left me a limited window of time to mature in my transition from one phase to the other. As we graduate from high school, however, we are still full of promises and dreams that have yet to be fulfilled. There’s this pleasurable thirst that just can’t be filled – and that’s good. Many of those dreams were shaped by the media we consume during our formative years: I grew up with the idea that college – the art school, the fine arts program – would be my own Hogwarts. I believed that, for the first time, I would go to this one place where all the people would be seeking the same things I was, but that somehow I would be able to maintain the protagonism that I had established during school up until that moment: I am the girl who can draw well.

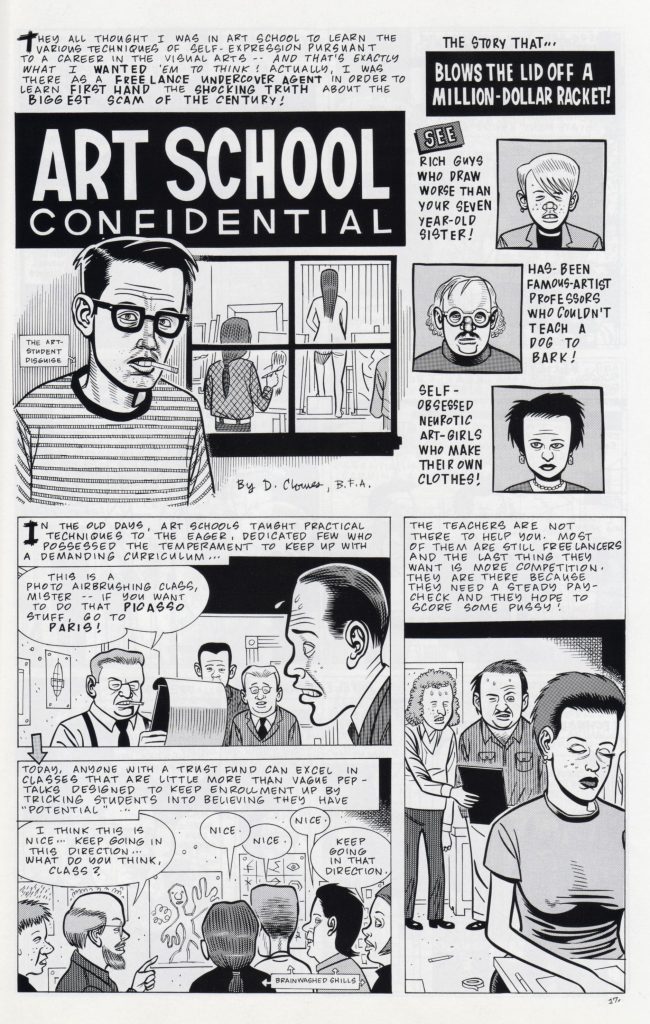

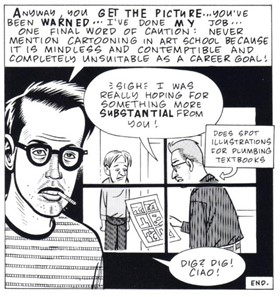

That’s pretty much how most of my classmates saw themselves, too. Art school would be a confirmation of my gifted talents, just like Jerome thought, in Daniel Clowes’ Art School Confidential (2006), a film inspired by a four-page short comic strip of the same name. Art School Confidential is a critical and satirical view of the atmosphere of a university of arts. As Clowes told in an interview for WIRED regarding the premiere of the film, the four-page comic was created as a filler to finish off the 7th issue of Eightball magazine: “I said, «Well, I’ll do something about art school that will amuse my 10 friends who went.» I really thought nobody else would comment on it or even notice.”

Clowes was taken by surprise when those four pages exceeded any expectation of popularity. Apparently, a great majority of his readers saw themselves in that satire about the environment of art education institutions. It wasn’t Fame at all. There were neither people dancing in the aisles, nor young people with indestructible aspirations and an enviable self-esteem. Instead, the readers recognized the ridiculous and incomprehensible, yet praised art displays, the pretentious language, their nagging teachers, ego squabbles, neurotic classmates, or the relentless grumbling.

And by including myself in the group of people who easily grew a grudge against their BFA, I can also admit that it felt easier to relate to its downsides than to anything else. When meeting up with old classmates, we easily fall into the temptation to spite our old teachers, reminisce over unfinished projects, joke about our naïve first-year selves.

Now, as a former art student and current art teacher, as I try to deviate from the cliché of negativity, I find myself more and more caught up in it. But why?

What happened to the childhood and teenage dreams during those 4, 5 years? What happened to the passion and will that made us choose this vocational path? Are expectation and excitement the precursors to a certain misfortune?

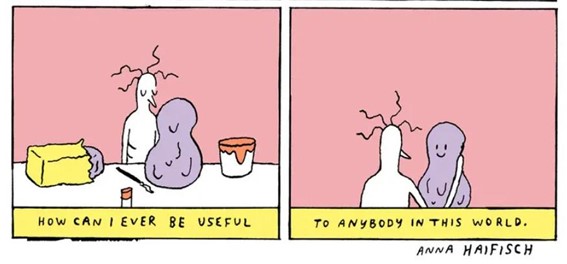

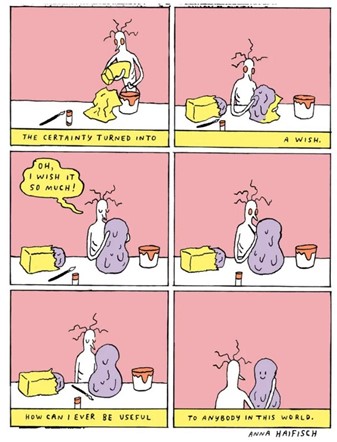

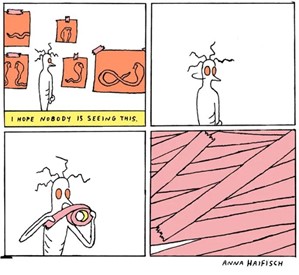

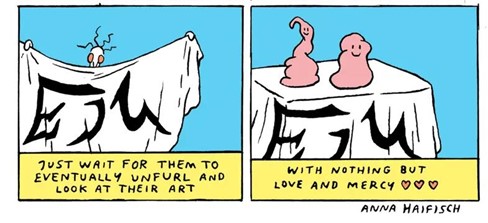

There is no doubt that there is an enforced fatality – Art Education must not be an enjoyable learning experience. But why? We’re drawn to accept that the Arts are doomed to exist as an elitist, toxic, and self-contained private club, that we dream to be welcomed in, someday (even if we don’t admit that). This idea is so commonplace that there is already a vast bibliography of graphic fiction around the subject: from Anna Haifisch’s The Artist to Walter Scott’s Wendy, through Joseph Remnant’s Cartoon Clouds and, recently, Kelsey Rotten’s Cannon Ball (and so much more). As I revisit the narratives that nourish my wounded ego, I fear that this negativism that looms over art practice is becoming way too romanticized, to the point that it has been made a requirement, the seal of authenticity that grants you’ve made it through art education, art world, and beyond.

Forget Everything You Have Learned

The satire of the art circuit begins in art education institutions. It is a constant struggle for many to prove that it is a necessary qualification – unlike a dentist, a lawyer, a veterinarian, or an engineer, an artist does not need a “license” to do their job. This bureaucratic matter ultimately triggers, in a mundane sense. the existential doubt that haunts any art creator – what is the purpose of what I do?

As I read Walter Scott’s Wendy, Master of Art, I recalled the countless times I was on the verge of dropping out of both my Fine Arts degree and my master’s in Film. Not because I was technically struggling with it, but because the lack of guidelines made it is very easy to forget my goals. Once again, what am I doing here, exactly?

In the beginning, as art students, we expect that an educational system, a venue that requires (supposedly) organization, deadlines, limits, and inspiring peers, will somehow regulate our artistic practice or, more concretely, assign a justification to what we already (think we) know how to do, whether it is drawing, dancing, or filming. We want tools, tips, and how-to’s to keep developing what we came here for. We are looking ultimately, even if unconsciously, for validation and, mostly, for permission. Someone who says, you draw well and you may continue. We need you to continue.

But once we are confronted with reality – and it doesn’t need to be one as cruel as Clowes describes in Art School Confidential – the validation and the goals we pursue are put at stake. No one is rooting for you. No one needs your art. You’re not special. These harsh phrases, that are, above all, generated by us to ourselves, penetrate our self-esteem as if they were exclusive to us. Such phrases hurt us as if they were insults, when in fact they are just obvious realizations. In fact, what does it mean to be special? And since when do we need validation to do something we were already doing anyway?

Great passion can turn into deep bitterness. It is through an attempt to accommodate to this new state of affairs that characters like Jerome, Wendy, or Anna Haifisch’s The Artist emerge. To me, more than satiric comics, they’re different processes of deconstruction, perhaps different attempts to understand an environment where the rules we’re expected to follow are perfectly subjective and shift as superficially as fashion seasons do.

Up On Melancholy Hill

According to classical Greek philosophy, the human being was composed of four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Every person would have these four humors inside in different amounts, and the variation in amounts would determine one’s personality. People who had an excessive amount of black bile in comparison with the other three humors were known as Melancholics. Aristotle was the first philosopher who directly associated melancholy with creativity. Later, during the Renaissance, Black Bile began to be associated with Saturn – with astrology being a core science at the time. Those who succumbed to a melancholic nature were under the spell of Saturn and, just as Aristotle had described, were generally introverted, withdrawn people with depressive tendencies. However, unlike Aristotle, in the Renaissance melancholic sadness was seen as a positive aspect – because it was associated with creative genius.

So, the relationship between certain personalities and creativity is a tale as old as time – and the idea that an artist is a shy, moody creature is as well. And from sadness, we can evolve to pain, suffering, and exhaustion. In the film Whiplash (2014), we watch a prolific drum student at a jazz school being gradually more and more bullied by his overly demanding teacher, Terrence Fletcher. There’s a constant doubt that triggers the premise of the film: for an artist to evolve and achieve excellence, is it necessary to undergo tremendous suffering? On the other hand, Fran Lebowitz on Netflix’s Pretend It’s a City, tells Martin Scorcese that she has never met any writer who enjoys writing. Any writer who actually likes to write, according to her, cannot be a good writer.

Before reading Scott’s Wendy, Master of Art, I was already a fan of Anna Haifisch’s The Artist. I learned about these comics on VICE, before buying the first printed book, published by Breakdown Press. The Artist has already been discussed here, in SOLRAD, by multiple authors. Alex Hoffman summarized the main conflict towards the Artist as a character: is he a stand in for the author, or an avatar for the other artist to relate to? Either way, as Hoffman points out: “As a character with no name other than “Artist,” created by an artist, either of these interpretations seems reasonable.” The word Artist is more than a general name, but a fuller concept that gives us clues about what we should expect of the character and their role in the world way before the story begins.

We don’t know much about the Artist as an individual, but we know what an artist is supposed to be. The Artist is melancholic, fragile, deeply sensitive, and any beam of hopeful light he encounters gets easily crushed by false expectation. Just like Aristotle believed, the Artist is a genius dreamer who can be easily led astray by procrastination. At the end of the day, he is a grown, but not more mature, version of Calimero – they’re simply, constantly, misunderstood. And, deep down, the Artist still hopes that one day someone or something will grant them their due appreciation, their true validation, and that they will be able to restore the passion that brought them to this path when they were still young. Haifisch is able to skilfully build a character and a narrative, that would easily fall into a self-deprecating cliché, into a poetic and romantic vision of what it is like to navigate and survive in the arts. Insecurities and weaknesses are often represented as inevitable fatalities from which our Artist can hardly avoid, but that with time and patience he will learn to cope. As Hoffman pointed out: “The joy in The Artist is knowing that he will continue along off the beaten path, even if it will sometimes bring him pain.”

On the other hand, Scott’s Wendy has a different tone. Also reviewed here at SOLRAD, Ryan Cary points out: “the Wendy books are both fun and eminently — sometimes painfully — relatable, as well as carrying an inherent whiff of the nostalgic about them for those of us (…) who find themselves involuntarily sliding into a post-middle-age demographic.”

In Anna Haifisch’s world, artists are usually shy and reserved individuals that must be approached with care. But in Wendy’s universe, including Wendy herself, artists are not magical creatures, they’re just people. Much like a sitcom, they come with all kinds of temperaments, as well as all sorts of flaws and attributes. Wendy becomes more than an “avatar” character – her personality evolves, her stories, although in an episodic format, establish continuity, being part of a larger narrative. Yet, Wendy is nevertheless the protagonist who guides us through the world she inhabits – in this case, the environment of the University of Hell, but being an artist or not, is not her main personality trait.

Wendy’s narrative tone draws closer to the satirical tone we have come to appreciate from Clowes’ Art School Confidential. Her colleagues and friends correspond to stereotypes that we can easily identify and that might remind us of someone we might have heard of: the obsessive guy constantly worried about being politically correct, the almost-famous colleague that seems to have everything going on, the one obsessed with very specific things (strings), the naive girl who makes nice things, but nobody really knows how she was accepted into the program in the first place.

Above all, Wendy’s adventures are still amusing enough to readers who have not been in the artistic scene. Just like in The Artist, there is a strong emphasis on substance addiction (particularly alcohol), on the compulsion to procrastinate, on the constant anxiety and self-doubt – things that all of us can undergo without being enrolled in an art master’s program. We are also aware of the stuff that goes on in her life beyond the master’s program – her wobbly friendships, her romantic entanglements, the quest for an apartment that isn’t hideous. The style of the drawing echoes its satirical view: Scott’s art shows an unpretentious, spontaneous, and honest attitude which contrasts with the idea we get from the snobbish artistic scene.

Just like The Artist, Wendy’s stories are broadly inspired by the author’s personal experience, and maybe that’s why it feels sincere and relatable. Francisco Sousa Lobo has written several comics regarding the same themes and feelings – usually autobiographic. In his two-page comic A Private View (2014), Sousa Lobo recalls the opening of his own exhibition. The classic constraints are all present: impostor syndrome, the dread of small talk, the desperation to make a good impression, to manage to maintain a minimally eloquent speech. But in Sousa Lobo’s comics – not just in this one – there’s another issue that’s not examined in Wendy’s or in The Artist’s: the problem about making comics within the art academic environment.

Don’t Draw Comics

Back to Clowes’ Art School Confidential comic, the spy/narrator concludes the comic by adding: “(…) One final word of caution: never mention cartooning in art school because it is mindless and contemptible and completely unsuitable as a career goal!”. He says this while looking at the reader, his face is numb, hanging a cigarette from his lips. Behind him, a teacher criticizes a comic board turned in by the student in front of him, cringing with embarrassment, as the tutor says that “I was hoping for something more substantial from you!” Right next to this,, there’s a text box with an arrow pointing at the same teacher, letting us know that he also “does spot illustrations for plumbing textbooks.”

In A Private View, the main cause of Sousa Lobo’s anxiety is the fact that he included a comic book publication in an exhibition at a contemporary art gallery, “and a very personal one at that”. The issue in here is not only the feeling of guilt and shame towards the choice of medium – comics – but also its content. Sousa Lobo may feel that a comic can be more easily perceived than a conceptual installation. Comics, for him, turns out to be a much more direct, and therefore more exposed medium, leaving him feeling even more vulnerable. “People go through it, unaware that it’s me, that it’s all real, and at the same time it is a fake.” As someone asks him if he’s the character in the story, he quickly denies it.

Like the Artist, Sousa Lobo’s tone is more melancholic than satirical. Yet, all the examples I named so far seem to agree that there is a common panic associated with exposure. In London Falling (2014), Sousa Lobo reminds us of the relevance of ASC as he shares his experience during his PhD in arts, admitting that the need to keep a pedantic discourse remains time after time. The academic discourse, overflowing with random references and quotations, is nothing more than another way of hiding our true ideas and opinions – and your true self. Art making can be tricky because it is a permanent conflict between showing and hiding. A piece of art can be both a form of communication and exposure, as well as a mask that prevents us from being completely exposed, placing an idea, a persona, in our place.

Although he may depict himself as an outsider, Sousa Lobo presumes that his peers experience the same insecurities and constraints as he does. Just like in Wendy’s University of Hell, they’re all under the same rules of social engagement.

At some point, these characters easily feel that the hoax world they live in is only supported by convincing verbiage. However, for many artists, verbal communication is not an easily acquired skill.

A Continuing Learning Experience

Just like Wendy, I started teaching while still a student. Like Wendy, I often found myself questioning whether I had the artistic and personal maturity to guide a group of young people along the path that I had only recently begun to walk.

But, as they say, you can learn a lot by teaching others. I am aware that I spent years feeling resentful towards my graduate degree, mostly because I felt that I hadn’t learned anything during those five years. Ironically, it was during my first years teaching that I realized everything that I actually had learned during my graduate degree. It is true that no teacher taught me how to hold a brush, few were even present in most of the classes. The theoretical classes, many of them, consisted of copying old books and cheating on exams. But, on the other hand, there are things I might not have learned in another way. Dealing with colleagues, establishing a work method, listening to and accepting criticism, and questioning that criticism, realizing what I like and, most of all, learning about what I don’t want and what I don’t like.

The back cover of Wendy Master of Art has a two-panel excerpt in which the teacher is asking “So, Wendy – Tell us about your work.” That excerpt is taken from a chapter in which Wendy shows one of her works for critique. This classic situation – asking an artist to talk about their work – is enough to make anyone laugh. I once had a workmate who used to say to me: if I could explain it, there wouldn’t be any need to draw it. For most, it seems to be an unnatural situation, to push someone to justify the unexplainable. On the other hand, some people feel it is an abuse of trust, a forced disclosure of vulnerability.

As artists, we are taught that, above all, we have to establish our identity. For those who stay outside, it seems to be a problem exclusive to those who have chosen this vocational path. But, to me, these are problems that concern each and every one of us. Who are you? What are you doing here? What do you have to say? Why are you doing this?

How badly do you want this?

Am I strong enough?

That’s when I remember what Rainer Maria Rilke advised the young poet, back 1929: “Nobody can counsel and help you, nobody. There is only one single way. Go into yourself. Search for the reason that bids you to write; (…) Perhaps it will turn out that you are called to be an artist. Then take that destiny upon yourself and bear it, its burden and its greatness, without ever asking what recompense might come from outside.”

I wouldn’t say that the end of the artistic education, nor the ultimate goal of any artist, is to find an answer to those questions. Perhaps because the answers may change depending on the different life stages we go through. The diploma is not a license. The school did not give me answers. Rather, it gave me tools to ask the right questions.

Despite all the setbacks and misadventures, Wendy manages to finish her master’s degree. However, when she reaches the goal that seemed further and further away – the thesis defence – she feels empty and numb when she gets clapped after her successful presentation – where’s all the enthusiasm? We, the readers, never get to see Wendy’s final project. Scott comically hides one piece behind the protagonist’s head, the other conveniently placed behind Maya’s hat. As Wendy reconnects with her best friend Winona, finds an apartment, and finally gets to talk to her love interest, Xav, with whom she abruptly ended things in the first half of the book, it is then that she realizes that it is not apathy she feels, but, rather, stability, peace. What else could be more frightful? Just before finishing the tour for my little sister at the art school I was attending, I remember passing by the sculpture workshops. Someone had left a radio blasting music, and two or three freshmen were dancing in the middle of the junk. I was thinking about the huge amount of dust and how it would trigger my allergies, but my sister said, “I highly doubt their parents forced them to apply to this school. It’s not like med school, or business school. People who come to this place are here because they chose to, because they really wanted to. They must love this.” There could be no other answer but to dance.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply