Reading Lane Yates’ review of Juliette Collet got me to thinking about this newer generation of cartoonists. It’s far too diffuse a group to make sweeping, blanket generalizations about them, but I think there are trends. That’s especially true in places where there are still distinctive, regional scenes, often surrounding schools in big cities like New York. When underground and alternative scenes were smaller and a discerning critic or reader could reliably have a handle on every relevant comic published in the US and Canada, those scenes were often reactive. By this, I mean they were reactive to broader movements in the culture as well as trends in comics, and it was often fairly easy to see the influences of even highly advanced cartoonists. Underground cartoonists were reactive to mainstream culture and many were highly influenced by EC Comics and Harvey Kurtzman, in particular. The alternative cartoonists of the 80s were looking at the underground comics and reacting against mainstream comics as the only game in town. Many were also influenced by punk rock, both in terms of attitude and the DIY work ethic that pushed the zine revolution to another level.

What’s curious about so many of the recent young cartoonists is that for many, it feels like rather than having absorbed the vast explosion of comics in the last 20 years, many have seemed to barely notice it. That includes the Riso revolution of the last decade or so, where craft and color became crucial aspects of comics-making for so many cartoonists. Many have seemed to show little interest in the kind of mainstream manga that influenced artists like Dash Shaw. If anything, as Yates pointed out, these comics feel a lot more like zines that might have been self-published in the late 80s into the mid-90s, back before the internet connected artists. In this three-part series, I’ll explore the work of several young cartoonists and key anthologies in an effort to get at the kinds of stories that are being told. The first entry will focus on R.Fay, Juliette Collet, and Caroline Cash.

R. Fay: Memory Book 1-4. Fay is a Durham resident and part of a remarkable scene local to the “Triangle” of Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill, and its environs. Jenny Zervakis, Andy Neal, Mark McMurray, Julia Gootzeit, Eric Knisley, Max Huffman (a young cartoonist whose output is worthy of its own article), and others are all here. However, Fay stands out with his devastating, hand-made Memory Books, each of which tends to focus on stylized depictions of extreme trauma.

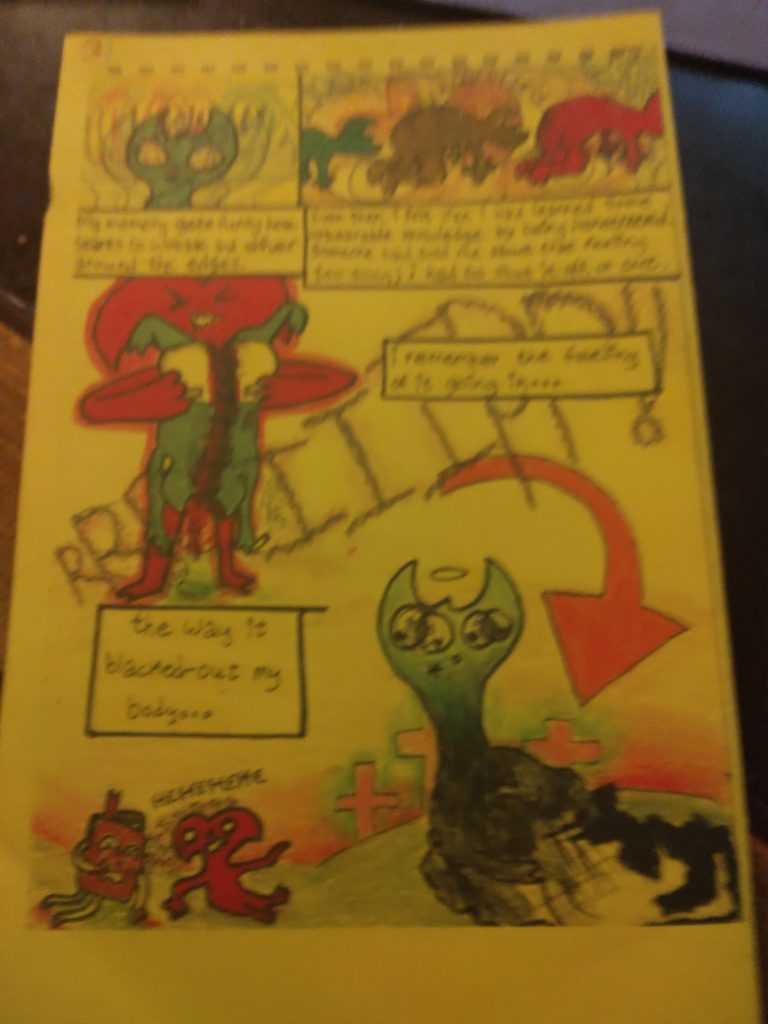

At this point, each of the four issues to date has been made entirely by hand on cardboard or construction paper and hand-colored with either marker or colored pencil. As such, they have a raw and immediate quality, that when combined with the content, feels like being punched in the face by a rainbow. Fay’s figure drawing is deliberately crude and colorfully monstrous, like figures from some children’s story gone horribly wrong. In the first issue, at just 4 pages, Fay recalls his first memory: deliberately holding his bowel movement, being found by his mother, and having a suppository shoved up his ass. Fay says that his memory wobbles a bit here, but that he also “learned some unbearable knowledge by being penetrated.” Fay isn’t interested in a narrative per se, but instead, there’s just a particular memory as a unit, presented in unflinching (but cartoony) detail.

Memory Book #2 is more reserved, as he jumps forward in time to a psychedelic mushroom trip he took with his boyfriend while they were in Australia. Even the colors are toned down in this smaller-sized mini (about 3 x 5″), making some of the details harder to fully understand, but the gist of the comic is fairly clear. Once again, Fay depicts himself as a sort of imp-like creature, up until he sees his reflection in a mirror coming down from his trip, causing him to pause and consider the troubled relationship he had with his family, and how it might be changing. Fay’s switch to a naturalistic style is jarring in a good way; it’s as though he reveals to the reader the different ways his synapses fire.

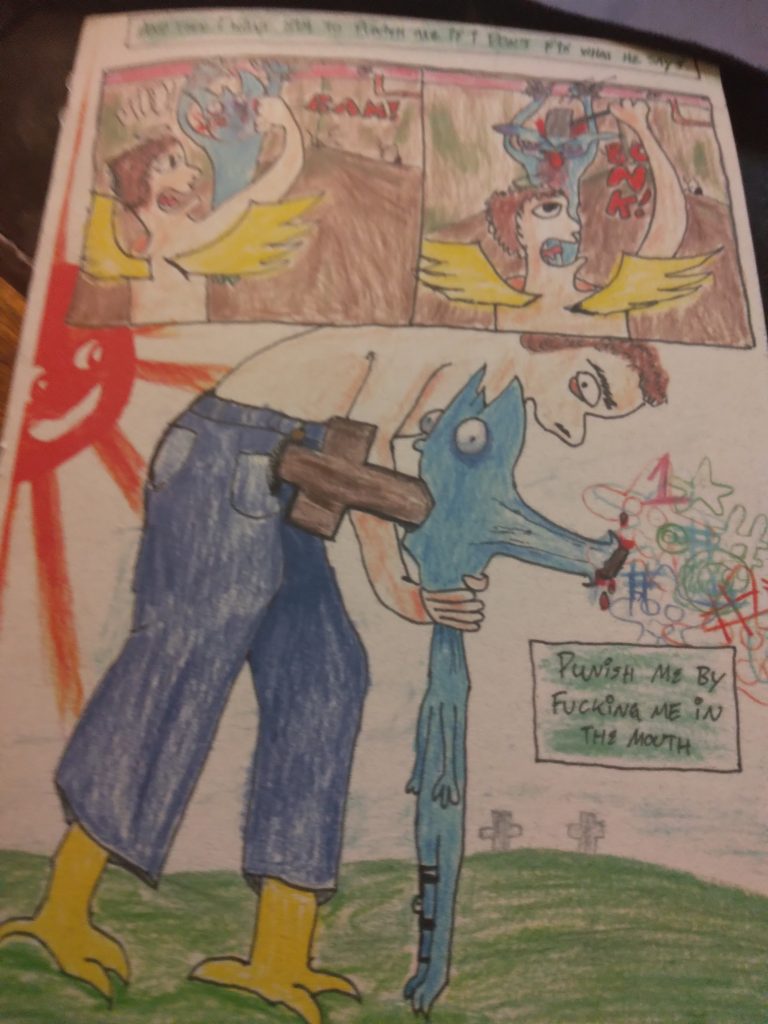

Memory Book #3: “Shrink” is Fay’s funniest comic. It’s a no-holds-barred fantasy about therapy, starting with feeling coddled by trauma therapists trying to validate his experiences. (There’s an eye pop where the babied Ryan has a book called “My Body Keeps A Whore,” a hilarious take on the well-known book about trauma “The Body Keeps The Score.”) Fay essentially admits that he fantasizes about things he doesn’t truly want: he doesn’t want a strict, sterile therapist, even if he thinks about it. He doesn’t really want God to be his therapist, tell him what to do, then fuck him in the mouth if Fay doesn’t do it, although he fantasizes about it. (The image of God fucking Fay in the mouth with a cross in his pants must be seen to be believed.) This switches to wanting a more loving BDSM relationship with God, then it simply drifts back to wishing there was a therapist who could fix him. This is a story reminiscent of the sort of thing Ivan Brunetti used to do in Schizo: over-the-top, raw, but utterly rooted in personal despair while looking for a gag.

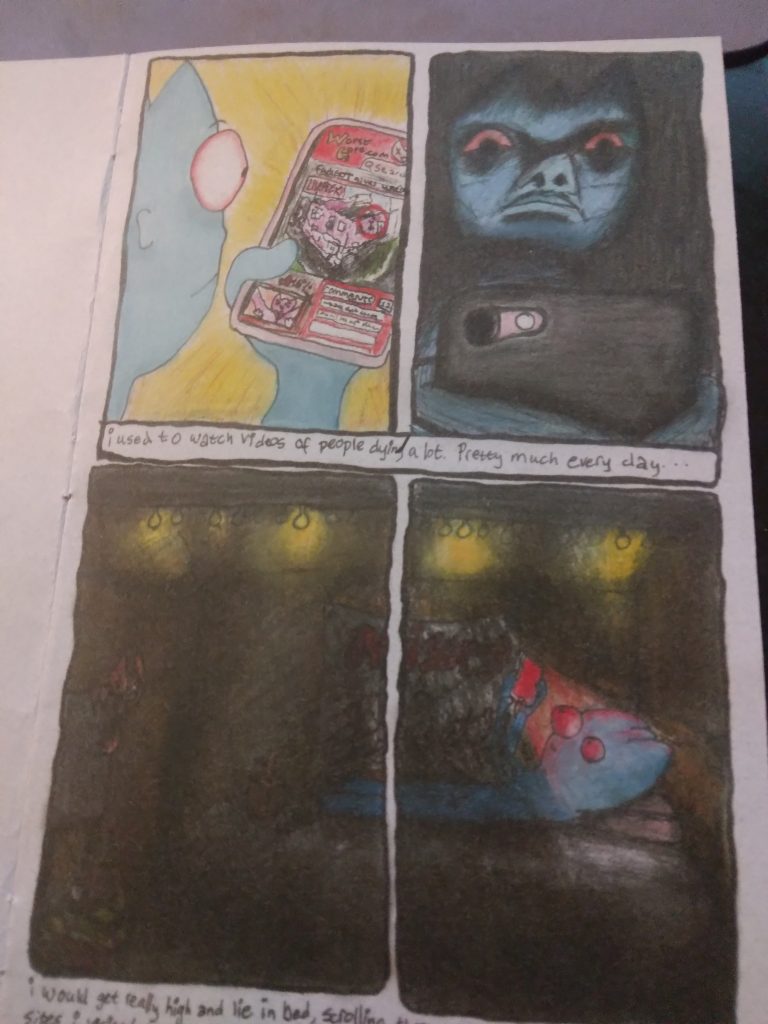

Fay goes much, much darker in Memory Book #4. It’s also an issue where one can see his command over his line and the use of color take a huge leap. This becomes important because Fay talks about a period of his life where, in order to combat his own depression and detachment, he would watch videos of people dying. He was especially interested in suicides, and he found their suffering to be comforting. Sharing this with his boyfriend at the time (depicted as a predatory vampire), the boyfriend (with a Grinch-like smile) said “This is the first time I’ve ever really seen you…” Fay describes a feeling of being not just feeling dead, but feeling rotten, like a putrid corpse, and he draws himself as he imagines what the Corpse Bride character looked like. He then leaves off once again, content to share a single, devastating anecdote. Across the board, everything about this comic is more sophisticated than in previous issues: page composition, lettering, the confidence of his line, and the more controlled use of color. He does all of this without sacrificing the raw and intimate style he established in earlier issues. As a storyteller, Fay is just writing fragments at the moment, but one can see in just these few pages that there’s something longer starting to coalesce. Fay’s utter fearlessness as a storyteller is his greatest quality, and he’s totally unflinching when picking at his old wounds. After reading so many sanitized, watered-down memoirs from big publishing houses, Fay is part of a young group that’s just an incredible breath of fresh air.

Juliette Collet should definitely be counted in that group as well, and this is another young artist who is not only totally unflinching in depicting the most intimate aspects of her life, she’s an astonishingly accomplished cartoonist and draftswoman who uses a wide variety of multimedia approaches in telling stories. One can also see a rapid progression in skill and confidence in her line in looking at the differences between the second and third issues of her self-published minicomic, Blah Blah Blah. While both comics pulsate with her creative energy, the third issue sees a more refined and even polished version of her art. Collet’s work really looks like nothing published anytime recently, even in an age where there are dozens of memoirs and memoir zines from young cartoonists. She totally eschews modern cultural references, and her work looks informed by 80s and 90s cartoonists like Phoebe Gloeckner, Julie Doucet, and most especially Dori Seda. (Collet told me that Gabrielle Bell showed her Seda’s work, which has largely been out of print for over 30 years, and she had to special order it from a library to see it.) However, while one can see the influences of these and other cartoonists, Collet certainly has her own visual language.

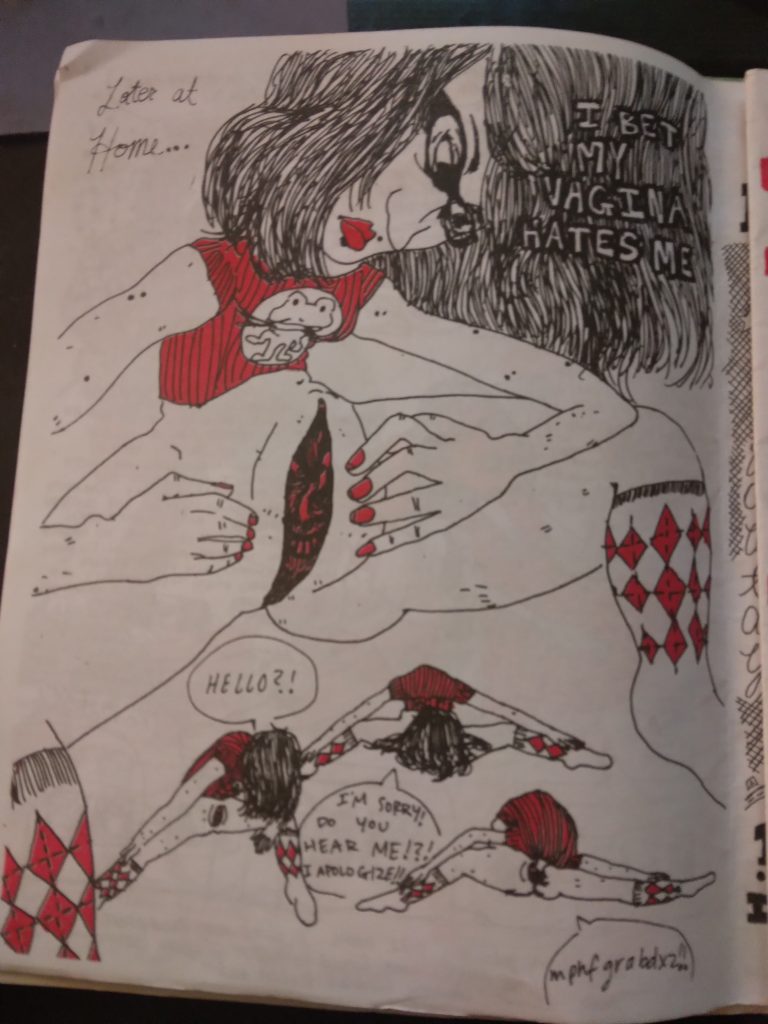

Her art veers between the whimsical and the grotesque, and her own self-caricature is a prime example of this. The oversized nose, the prominent mole, and the sunken eyes all make for iconic material, whether her head is distorted (like a Gloeckner drawing) or her pages are dense with cross-hatching and blacks (like Doucet). Seda’s sense of whimsy and melancholy inform it the most, as Collet draws a funny song-comic about the “Oopsie Girl,” which has a cartoony set of images that mixes raw sexuality and desperate emotional yearning. That’s a good summary of Collet’s work in general. Her comics about sex are not erotic and certainly not meant to titillate; instead, she’s trying to express the lived experience of physical intimacy, especially when it’s sometimes not all that pleasant. Sometimes, it’s just absurd. Her work repeatedly refers to her conflicting characteristics of the desire to withdraw and the need to connect. She can pivot from philosophical conversations about sex, love, and meaning with a friend to a strip where she apologizes to her own vagina in the most ridiculous way imaginable.

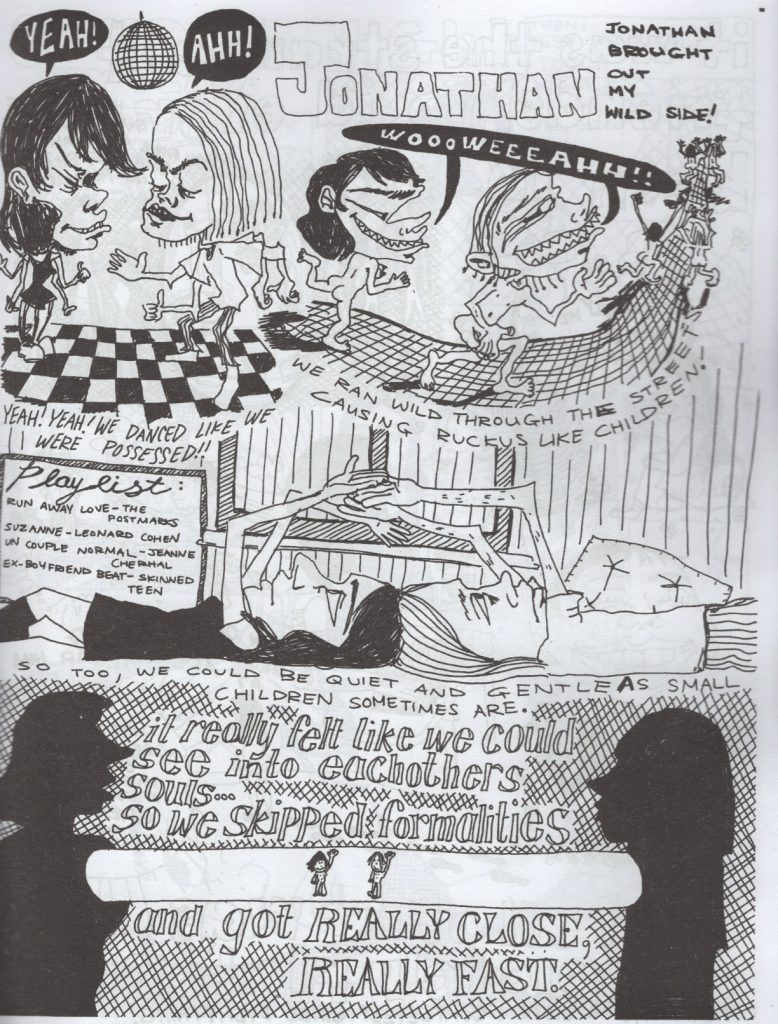

The thing about Collet’s work is that despite her protestations of isolation, she spends much of her time writing about her friendships with other people. Blah Blah Blah #2 features a beautifully-cartooned story about a young man named Nathaniel, whose eccentricities fascinate her and whose drawings of Collet make her realize he sees her the way she sees herself. Another strip about a female friend explores their conflict and how Collet eventually reinitiates it because she misses listening to her. This one is done all in red, with the panel borders all decorated in a different manner, almost as though it’s being staged. A story about a platonic friend named Jonathan is the best piece in the issue, in part because her cartooning is so beautifully intuitive, grotesque, and distorted while still retaining an essential sense of humor. The way Collet integrates her lettering as an essential piece of the art itself speaks to her understanding of composition, even when in her earlier work where her lettering is sometimes cramped or awkwardly placed. The story is about a platonic relationship that she ruins after she proposes sex one night. The sheer density of the cross-hatching puts the distorted figures in sharp relief, as she switches from sharp angles in profiles to almost naturalistic giant heads on smaller bodies. It leads her to withdraw from the risk of engagement and sink back into her own head.

Blah Blah Blah #3 is a stylistic whirlwind, as Collet experiments with photocollage, whimsical fantasy drawings, using colored pencils against negative space figures, a hilarious pin-up poster shot straight from pencils and collage elements, and a bunch of other different attempts at storytelling. Collet claims that it’s all because her life isn’t interesting enough for memoir, but then she did two incredibly engaging autobiographical stories, both of which are completely different from each other. One thing Collet likes to do is find a way to play with the fact that she has to draw herself endlessly. In the endpapers of this issue, she draws herself naked, but her body has a variety of patterns: polka dots, argyle, rainbow stripes, etc, as though she was making cutout dolls. On the indicia page, she cuts and pastes photos of herself with an oversized head (a recurring motif) and makes her “dance.”

The first autobio story once again reveals that Collet’s best skill is in creating nuanced, beautiful visual profiles of her friends. Visiting her college friend Madeline as a surprise for her birthday, Collet creates a portrait of an intellectually curious, emotionally giving, and daring person who helped Collet blossom as a person. The dynamics Collet depicts at Madeline’s birthday party are hilarious, as she seethes with jealousy over every one of Madeline’s many male friends. When one tells her he read her comic, he tells her with a haunted look on his face that he hoped she was OK. A horrified Collet realizes that what she saw as humorous stories, others saw as expressing deep loneliness and isolation. Both things are true.

There’s a story about a punk band made up of animals and insects with photos of faces for the character that are otherwise drawn in a thin, delicate line and decorated with pastel colored pencils. This story was constructed as much as it was drawn, as Collet completely eschews the use of a typical grid but still has total command of the page. This is even as she alternates between typical left-right reading for the reader to then reading the left column from top to bottom and then the right column in the same way. It’s jammed with drug humor, band dynamics, angry punk attitudes, and the whimsy of delicate insects playing loud music while high. Speaking of whimsy, that’s followed by a wordless strip of three different versions of Collet dancing with each other: one wearing a child’s bat outfit, the nude polka-dot version, and one dressed in a wolf mask. It’s a pure distillation of movement and form on the page, as she once again plays with her self-caricature.

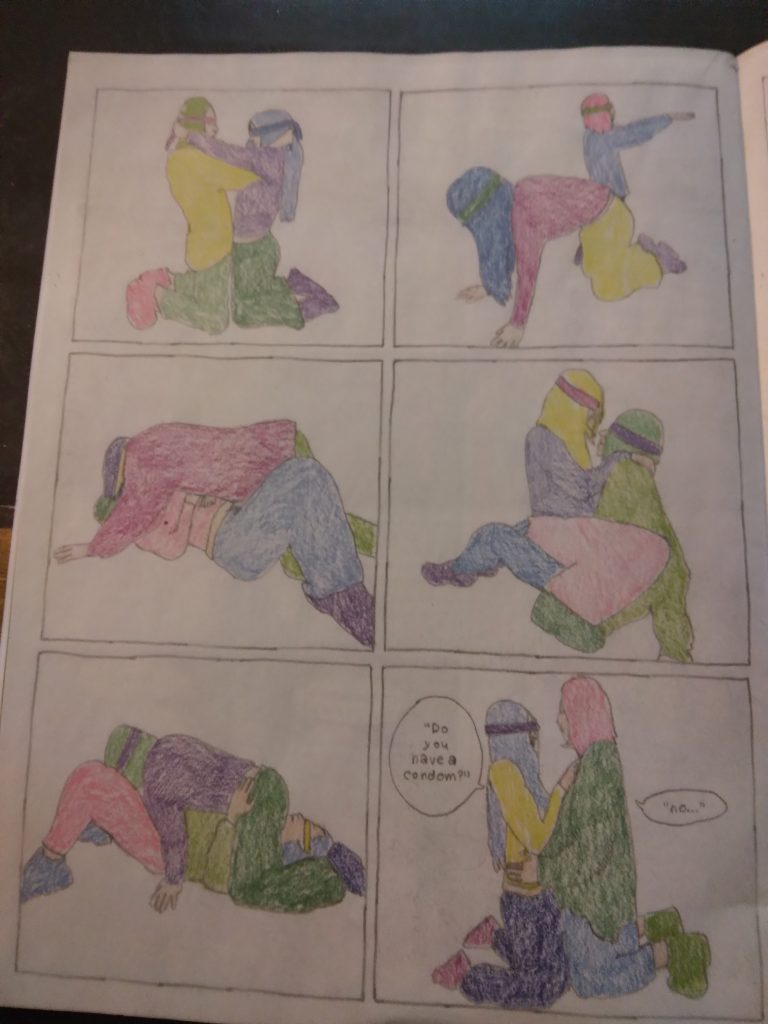

The second significant memoir entry in Blah Blah Blah #3 is “Double Blindfold,” which uses photo references from two models who recreate a particular set of encounters between Collet and a casual hookup named Mitchell. The photo reference is used just for character outlines, as the line is fairly rudimentary; it’s her use of colored pencils in creating a constant, nervous energy that makes this fascinating to read. The story itself is both frank in its depiction of sex (and Collet’s simultaneous sense of need and ambivalence in relation to it) and the weirdness surrounding these kinds of casual relationships. It’s ultimately a series of ridiculous gag sequences involving stepping in shit, the need for “medical grade” wipes to clean sneakers, a metacommentary on the ethics of depicting others in memoir, and an intense scene dipping into kink. It’s fascinating to read because the drawings come from staged scenes that are then abstracted into hot and cool colors designed to manipulate the emotional response of each panel. Collet’s work is equal parts first line/best line expression and deeply calculated and planned effects. The essential vulnerability and uncomfortable intimacy of her comics were only heightened by her increasing confidence and experience as an artist, and I can only imagine that this will continue to be the case.

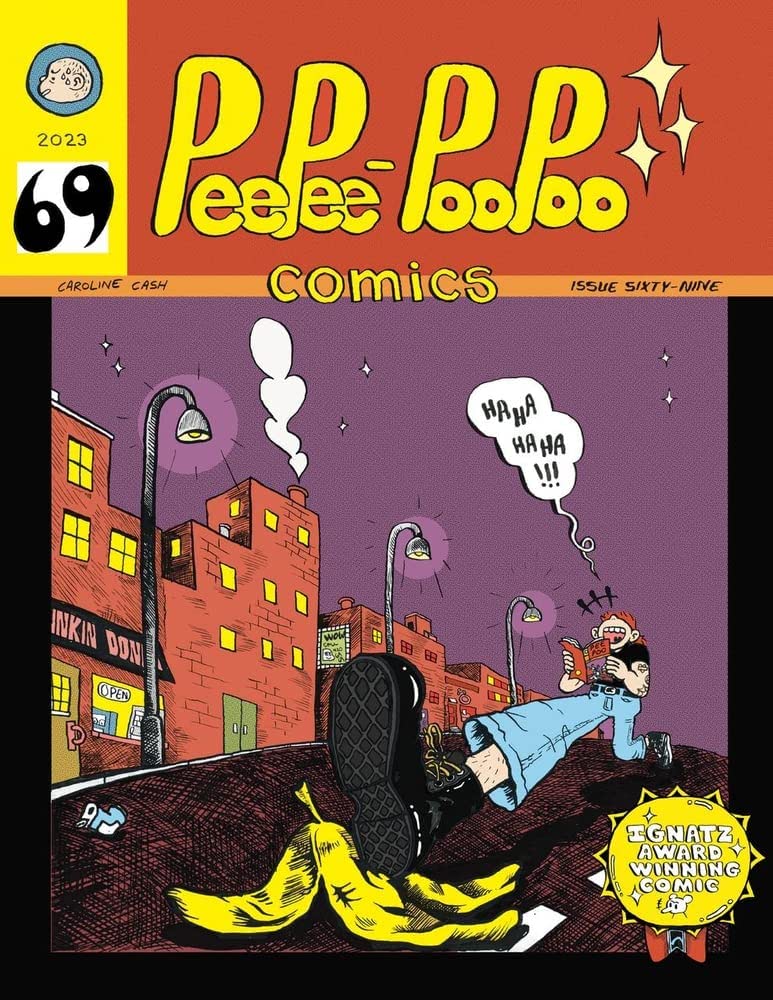

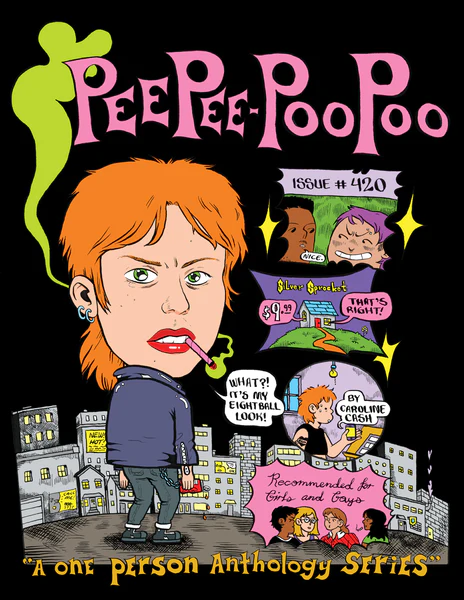

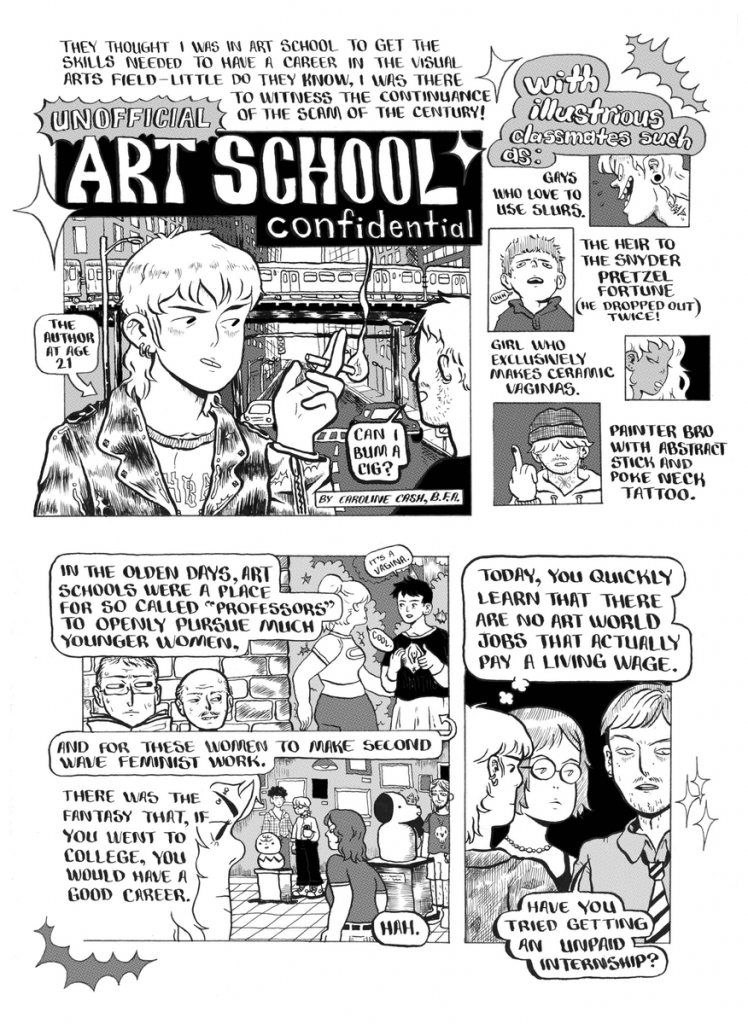

If Fay and Collet represent a fiercely raw expression of intellect and uncompromised vulnerability, then Caroline Cash‘s comics feel slick and distanced in comparison. If Fay and Collet seem almost disinterested in the comics community and comics tropes in general, then Cash’s work can be seen as one long critique of what was once a mostly straight-male-dominated world. Indeed, a lot of Cash’s jokes require the reader to be in on the joke of what she’s mocking. Even the title of her one-person anthology, PeePee PooPoo is taking the piss out of edgy underground comics. The first issue’s (labeled #69) cover is a parody of Robert Crumb. The very first page is a splash drawing of Cash as “peeing Calvin” flushing Crumb’s head down the toilet. This is a direct reference to strips where Crumb depicted himself pushing a woman’s head into a toilet. The second issue (#420) is a direct reference to Daniel Clowes’ Eightball #13, subbing in Cash herself for Enid Coleslaw of Ghost World. This is less parody than true homage, as she does her own version of Clowes’ short story “Art School Confidential.” Clowes was a Chicago guy before he left for California, and it’s clear that Cash sees herself stepping into this role in her comics.

Cash’s line doesn’t resemble Clowes; if anything, there’s more of Charles Burns to be found in her character designs than anyone else. She plays most of this for laughs, like in a post-apocalyptic hang-out comic that starts PeePee PooPoo #69. Cash plays off the banality of social interaction against the horrors of what’s happening in the background. Her “Art School Confidential” story, updated for modern times, is hilariously savage as it follows Clowes’ template but goes in some different directions. For example, in the list of people you meet in art school, Cash lists “the most complex polycule (that you will never have a chance of understanding),” with Cash being sweatily confused by the interactions of eight different people.

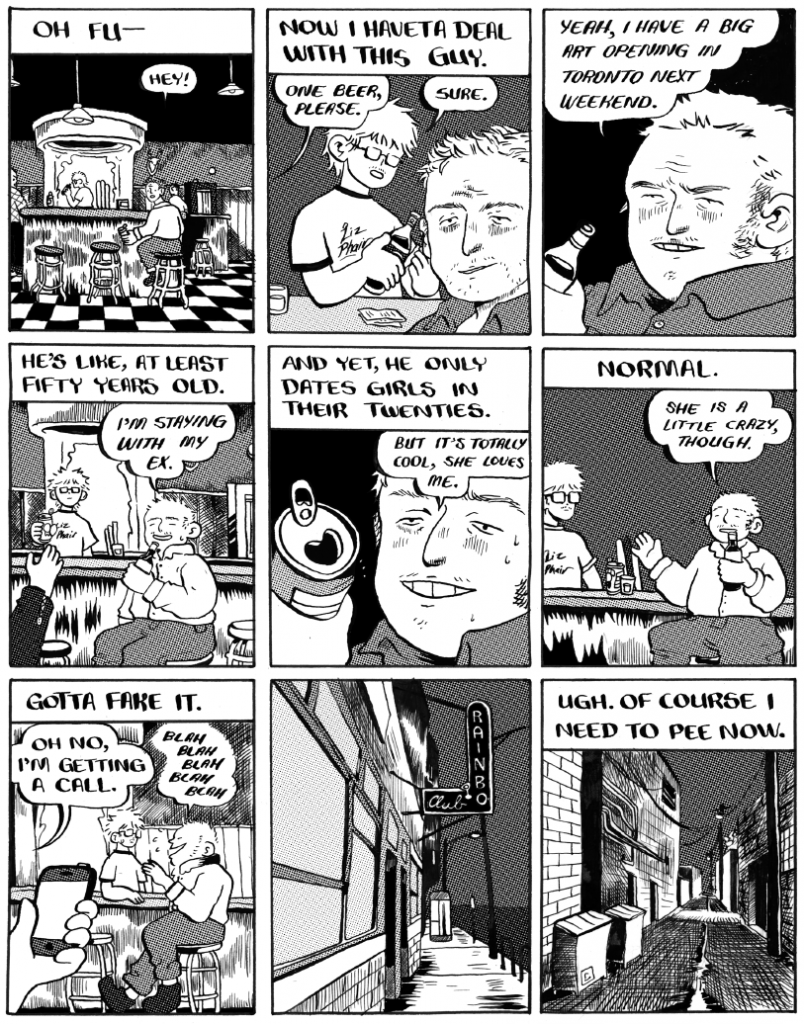

Cash is a smartass, but what sets this comic apart is her slice-of-life stories taking place in the bars of Chicago that are sweetly romantic or, conversely, depict painful heartbreak. In stories like “One Beer” and “Come Home To Me,” Cash uses late-night Chicago as a sturdy backdrop. “One Beer” is about a friend date between two women that goes in an unexpectedly romantic direction. It’s clever because it begins with one of the women complaining that women are hard to flirt with, until the other woman shows her a surefire flirting strategy that works to perfection! “Come Home To Me” depicts the kind of 3 am conversations friends have in all-night bars that’s interrupted by a voice from the past. This is the first part of a longer story, but Cash expertly establishes the stakes in building up this mysterious woman from the protagonist’s past. Cash’s background detail in both stories is impeccably trashy and sleazy. She’s clearly someone who’s spent a lot of time people-watching, and she makes the weird background characters in bars pop. Cash makes it clear that they all have their own stories, most of them unsavory, but she’s just not focusing on them.

There’s one specific way in which PeePee PooPoo reminds me of Clowes’ Eightball. It’s not the anthology format or the Chicago connection, which are both obvious. When Clowes started Eightball, it was a conscious and highly confident redirection from what he had been doing before. You could tell that this was a cartoonist who was hitting his stride. The same is true for Cash with PeePee PooPoo. As much as she’s laughing at outdated comics conventions and attitudes and uses that as an initial hook, the real value of these comics is seeing how confidently she goes from memoir to slice-of-life to absurdist humor to observational comics. If Cash is more clearly reacting to the comics establishment than Collet or Fay, one gets the sense that it’s part of a process of gleefully cycling through these influences on her way to memorable long-form comics.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply