I grew up in a household less atheist than largely antitheist. My mother grew up in a kibbutz, an environment that, if not rejecting religion outright, certainly did not acknowledge it as an option; my father—a city kid whose family, if it was ever devout in any way, had largely left these old ways behind in pre-WWII Poland some generations prior—rejoiced in a boyish in-your-face iconoclasm, and was not much for custom, ritual, or being told what to do. For the bulk of my formative years, then, the spirit was a construct altogether foreign to me, gladly external. It was only in recent years that I began to experience what I would describe as an inverse crisis of faith—a deep desire to believe in some manner of Great Eternal, some extra-temporal anchor, but a failure to articulate exactly what that means, in practice.

I do not know if Aidan Koch shares any of these background experiences, but her comics certainly have the end-point in common. They are inquisitive, vulnerable things, whose curiosity seems bilateral, almost—a desire to understand environment is balanced with a desire to understand self, and to be understood in that same breath. It’s likely that, asked to describe Koch’s work, many readers would use the same semantic vicinity of descriptors: “quiet,” “tender,” “tentative.” Sean T. Collins wrote all the way back in 2012 that “much of the power of her elliptical comics stems from things left unsaid,” and this was three years plus change before her first collection of zines and mini-comics, After Nothing Comes, was published by Koyama Press. Yet, twelve years later, with the appearance of her second collection, Spiral and Other Stories, from New York Review Comics, Koch certainly hasn’t gotten any louder—if anything, she has ventured further into the ambiguity of her form.

Consider, in this context, her sense of page layout. Where Koch’s art comes truly alive is in her negative spaces: her backgrounds, more often than not, are nonexistent; her depiction of environment rarely goes beyond vague texture. She activates an intimacy that goes beyond the sparse gesturalism of theatre, almost eschewing spatiality altogether. Where man-made structures appear in her work, it is as ruler-straight but almost-disparate lines: the house in the titular story, “Spiral,” only scans as a house through its positioning relative to the people inhabiting it; if not for the people standing next to them, its lines would approach the abstract. Her depictions of nature, meanwhile, enhance the tactility, “blocking out” space with thick washes of watercolor; precision, though, is still done away with as these shapes are rendered legible through relations of color. This practice of cartooning as reduction, as distillation, forces the reader not only to take a more active part in the interpretive process but also to consider the very essence of human three-dimensional space and perception thereof.

At ten chapters taking up roughly two-thirds of the collection, “Spiral” is the most substantial of the pieces, having been previously released in French as its own graphic novel before its English appearance in these pages. The odd-numbered chapters of the story focus on an unnamed artist who, before going off to stay on a farm in an attempt to recalibrate, stops over to stay with a couple of friends, Yann and Lise. Although the protagonist’s love for both friends cannot be denied, there is a certain distance between the two parties; she describes their home as the set of a performance, while the couple, for their part, seems to treat the rhythmics of home life — hosting guests, building a lake-house — almost as a distraction. I cannot help that “Spiral” picks up where “Reflections,” the final piece in After Nothing Comes, left off. In that piece, two young women unexpectedly reunite after a long time apart. Their conversation, rife with pauses and unspoken ambivalences, ends like this:

A: Do you ever feel like you’re building walls?

B: What do you mean?

A: Closing yourself in… protecting yourself.

B: From what?

A: Everything.

The protagonist appears to bear some unresolved romantic baggage toward Lise, only hinted at through the concurrent narrative depicted in the even-numbered chapters: here Koch does away with human characters entirely, offering instead descriptions of nature, embodied in two bodies of water, flowing together into one. There are overtures to the broader ecological concerns that appear in later stories in the collection — the narration in the fourth chapter invokes the “visitors” that affect the flow and depth of the water, which the moving water forgets but the fixed mountains remember — but these can be just as well interpreted as the unexpected knife-twists of human relationships.

Most noteworthy in these chapters is the pointed way in which Koch employs anthropomorphism to underscore the failings of human-centric thinking, and, even more personally, the trappings of human emotion. “The water never thought about what would happen,” she narrates in the sixth chapter. “How it would transform, how it would grow + dissolve, how it would lose the shape of its body. It was just moving.” Koch articulates this with no small amount of envy: the water, in its lack of sapience, operates in a mode of pure instinct. Water is a recurring motif in the collection, and it is perhaps the perfect vessel for Koch’s emotional landscape: a “body of water,” after all, is a body without discrete organs — it does not know how, nor does it seek, to divide itself; it exists in complete unity and harmony, a perfection of flux.

It should come as no surprise that the tenth and final chapter of “Spiral” sees that alternating structure of abstract and literal break down; a cardinal rule in Koch: in a long enough timeframe, the key function of boundaries is to erode. After what appears to be a flashback between Lise and the protagonist, in which they talk about their then-future (Lise with Yann, the protagonist with a partner who has since left the picture), or a more optimistic view of the future that did not come to pass (Lise visiting the protagonist at her new home, the protagonist having more time to focus on her art), Koch shows us a final wordless sequence of the two bodies of water reaching their ultimate marriage before transitioning into the protagonist settling into her room in the farmhouse.

The farm-owner’s grandfather was an artist himself, and the owner gifts the protagonist his old materials; what appears to be a painting by him, depicting a body of water rendered in the same manner as the portrayals of previous chapters, hangs on the wall. Man-made art has an ambivalent standing in “Spiral”: earlier in the story, Yann shows the protagonist a standing stone erected and carved some three thousand years prior, raising the possibility that it is the only one remaining of numerous others like it. Art, then, is simultaneously a marker of human survival that transcends the bodily—and an existence in perpetual risk, one that needs to be guarded.

Koch leaves us, and her protagonist, in a place not too far from where she started: looking off into this painting (whether she recognizes herself in it or not), and into this new start, with, presumably, quite a few mixed feelings. One recalls Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata (as quoted in My Dinner With Andre): “I could always live in my art, but never in my life“; or the tentative, simple connections of Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days. A life spent in fear of unmediated existence, in building walls to protect yourself: one wonders whether that is really any life at all.

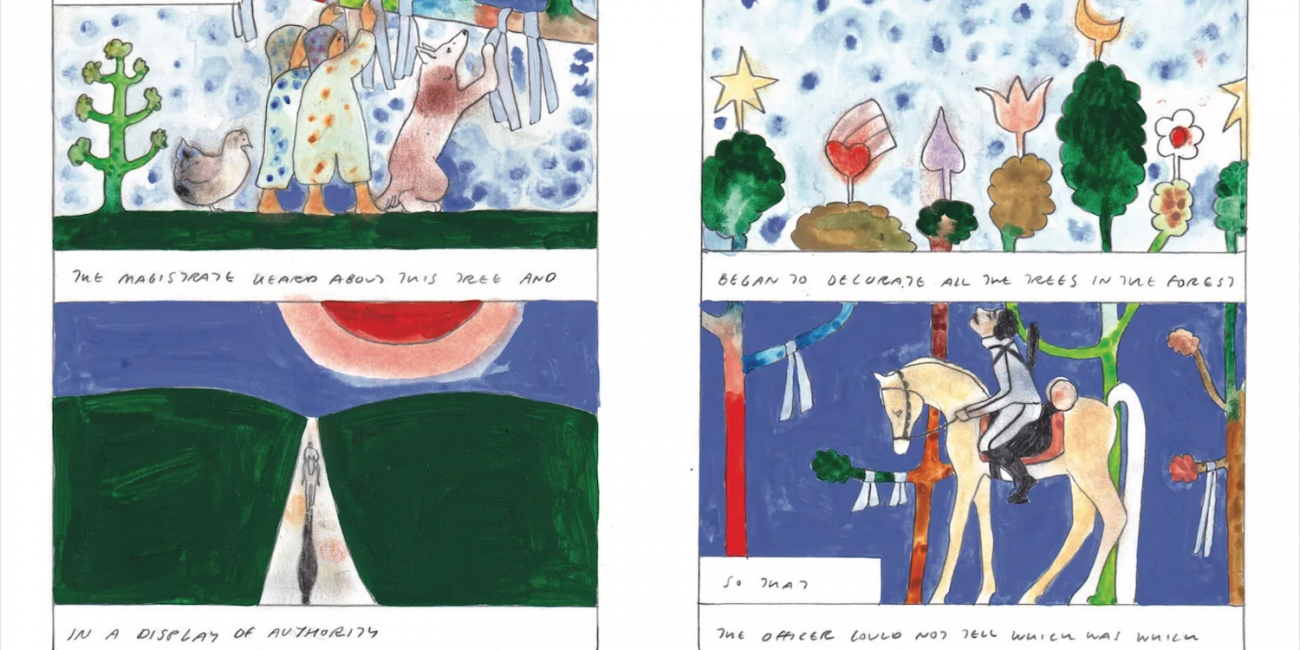

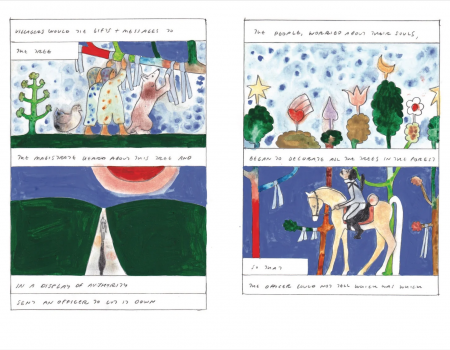

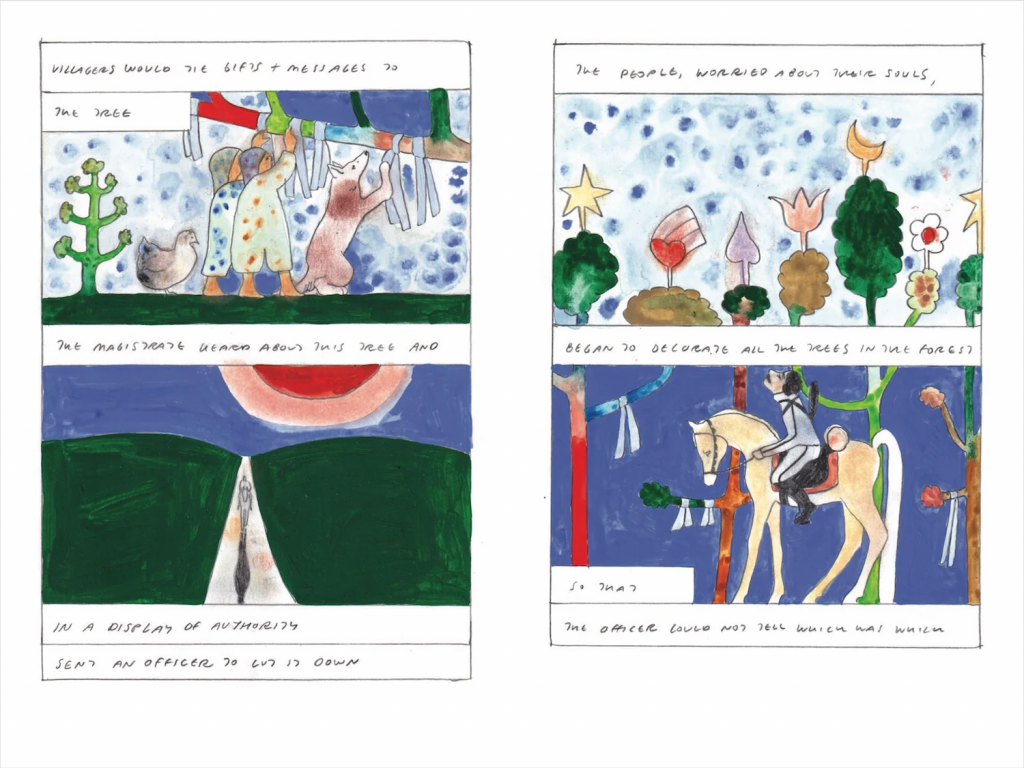

The next story, “A New Year,” literalizes the connection between humanity and nature through a lens of ritual and folklore. Set on New Year’s Eve, it portrays two girls on vacation in a rural town with a cultural background of animism. As one girl relates to the other, many generations prior, the town used to house — and venerate — a tree that would house the souls of the dying prior to reincarnation; when the authorities, as a pure demonstration of force, came to cut down the tree, the townspeople simply decorated all of the trees in similar manners so the powers-that-be wouldn’t know which one to cut down. Yet, as a result of that, the townspeople themselves lost sight of the “original” tree, at which point the tradition became genericized, nonspecific; even though most trees were nonetheless cut down for fuel over time, the tradition itself survived.

Here we have a push-and-pull affair, a crystallization of folklore that, as it ascends into the “cultural” plane, loses its roots within the concrete and material world. The tree begins as a singular, focused unit, both rooted in its cultural context — the belief in the contribution of all living things in the town, even, and perhaps especially, the non-human — and then, by necessity, its significance is “decentralized” in order for it to survive, even past the death of the literal roots. To a great degree, there is an element of defiance against authority there as well, the locus of power changing from the literal authorities to the powers of commerce.

There’s a natural ambivalence surrounding these changes; the loss of roots raises the risk of entropy, as the tradition is carried out by force of momentum without active dialectical engagement. The setting of the story itself is significant: New Year’s is a time of ritual, a celebration of cyclical and seasonal time, i.e. a projection of significance onto the largely arbitrary, yet its modern-day celebration has very little to do with natural seasons; the two girls that Koch focuses on are likewise external spectators—they take great pleasure in their change of scenery, yet when their vacation ends they’ll surely go back to their city homes, removed from this site of greater “connection.”

Koch, however, appears ultimately optimistic; in spite of these erosions, the folklore nonetheless ultimately results in community-building, in the reinforcement of the shared collective infrastructure, and this vacation allows even those two girls, who by default view this scene as “exotic,” to partake in it more actively. They decorate the trees or at least broach the idea; they see the stars which their usual urban light pollution prohibits.

Koch takes an approach of almost childlike wonder in drawing “A New Year,” transcending the literalism of proportions and specifics into a realm of almost Platonist generalities. The foliage is drawn in the elliptical swirling of children’s trees, no particular genus attached; the animals of past generations, their contributions greatly valued by their human cohabitants, take on unusual physical proportions and function: a grasshopper looming taller than a woman reaping barley, a dog standing on its two hind legs to decorate a tree. Perhaps, the cartoonist appears to say, this idealism of folklore is childish, naïve — but then, in the formation of a strong communality, perhaps naivete is not altogether without its value.

As the two girls step out to look at the stars, one large red five-pointed star shines overhead; the last page sees it, inverted top-down, nested atop the trees. A more genre-minded creator might intend this as a horror “twist” — they were Satanists all along! — but I don’t think this is at all the intent here (if anything it’d be more a remark on the demonization of nature-minded paganism by religious hegemony, but even that I think is a reach). More striking, however, is the pencil outline of a horse near the tree on the right-hand side. Blending into Koch’s watercolor washes, it’s easy to wonder whether this detail, drawn then promptly abandoned in its early stages, was intended for final visibility. Fitting, given Koch’s own animist-spiritual themes: past lives — artistic, biological — survive forevermore.

“The Forest” is both the shortest and the loosest of Spiral‘s four pieces, affording Koch an opportunity to explore a mode of comics less narrative than purely observational. Its twelve pages offer a succession of images for which the narrator, perhaps Koch herself, serves almost as a locus. It’s a simple enough piece to describe—the narrator tours a forest, finds a river, and enters it as the rain starts to fall — except nothing is ever simple with Koch; here, perhaps more than any of the other three stories in the collection, the author serves up an almost childlike celebration of pure sensation.

The noticeable divergence of “The Forest” is the lack of contours: Koch’s smeared watercolors have a generalized, freeform quality to them; their components, trees and earth and water, are sometimes clearly distinguishable from one another, completely melting into one another at other times. And that porousness is, of course, what Koch is after. Her lettering, too, is even more casual, a scrawled whisper of cursive that is offered on the margins of the art rather than right on top of it.

Koch employs an interesting technique in her depiction of the forest, alluding to other forms of life while not showing them overtly. Her narration transcribes bird calls where only still trees are shown; she invokes a passing boat where her art shows only the protagonist, melting into the water in a tender, almost kiss-like motion. One stops to wonder, for a moment, what — who — truly exists autonomously in this world. But individualist autonomy, if it exists, has no place in Aidan Koch’s world.

Koch’s pursuit of the eternal culminates in “Man Made Lake,” which, for the most part, snaps back into a more overtly narrative mode. Originally released as a kuš! mini-comic in 2020, its first third is a dancelike preamble, displaying almost Matisse-like contortions of the human form, as well as a handful of shark-like sea animals (Koch’s tentative linework lends itself to an openness of identification), all painted in with gradients and patterns that invoke nature: the ocean, the sky at sunset, the gills of a fish. From the very beginning, the living and the supposedly-”still” are contained within one another, complemented by one another. Koch then transitions into a therapy session, wherein a short-haired protagonist describes his recollections from a past life, one with a much deeper connection between bodily self and environment. “My cells were part of everything,” he narrates, “and everything was connected.” He describes this as perfectly palpable, not a detached semi-fiction: his “becoming human,” he recalls, was achieved when he was about four years old; “my sister,” he says, “was a frog until seven.”

But, though the patient views these as past sensations that will never be repeated, Koch is not so sure. The ending sequence of “Man Made Lake” is a fitting closer to Spiral: after listening to her patient’s experience of past lives, the therapist closes their session and leaves her clinic. Stepping out to the blank modern landscape, punctuated with color and texture delivered by the vestiges of nature that still remain in the city, she pauses in a moment of recognition as a bird flies overhead; Koch goes one step further as to employ collage imagery of trees and birds, at once incongruous and tactile. “Hello,” she calls out, on the final page; then, again, “Hello?“, a question this time. But something happens between the two entreaties — she loses her distinguishing features, while the formerly colorless air around her, as well as her uncolored skin, take on an ecstasy of blue and purple.

It’s a lovely transition, one of the most effective singular pages I’ve seen in my years reading comics: the impact is akin to a sharp inhalation, a jolt of spiritual and existential renewal — then ending, as if to send reader and character alike into an infinite potentiality, reassuring them that, despite it all, connection lives on, indelible. Again I think of that exchange from “Reflections”—if this guarded feeling lies at the heart of After Nothing Comes, then Spiral and Other Stories pursues the opposite feeling; over the four stories, Koch not only recognizes the connectedness of all things but seeks, actively, to enforce connection, to break down the barriers. Defense becomes not a matter of building walls but of feeling at peace with their nonexistence.

One may note that “A New Year,” “The Forest,” and “Man Made Lake” all share the trait of the protagonist- or narrator-as-witness; the function of the human individual, in these works, is a cultural-collective one, bearing witness first and foremost, changing as little and retaining as much as possible (the same can be said for “Spiral,” to an extent, though the scope of that story is more interpersonal). Yet this is not in the interest of a conservative stasis, not a fear that what is labeled “progress” is, in fact, regress, nor is it a romanticizing of an abstract ‘nature’ that exists merely as the privilege of escape; more than anything it is the search of a pure and uncontaminated knowledge, to the point of pure immersion and unity. It is only from this point, Koch seems to say, from this ongoing search, that a true life — of spontaneity, of bilateral authenticity and intimacy — may emerge. And Koch does, with the ending of “Man Made Lake,” make the effort to emphasize that this connection is within reach (even if one does have to work, actively and with intent, to achieve it).

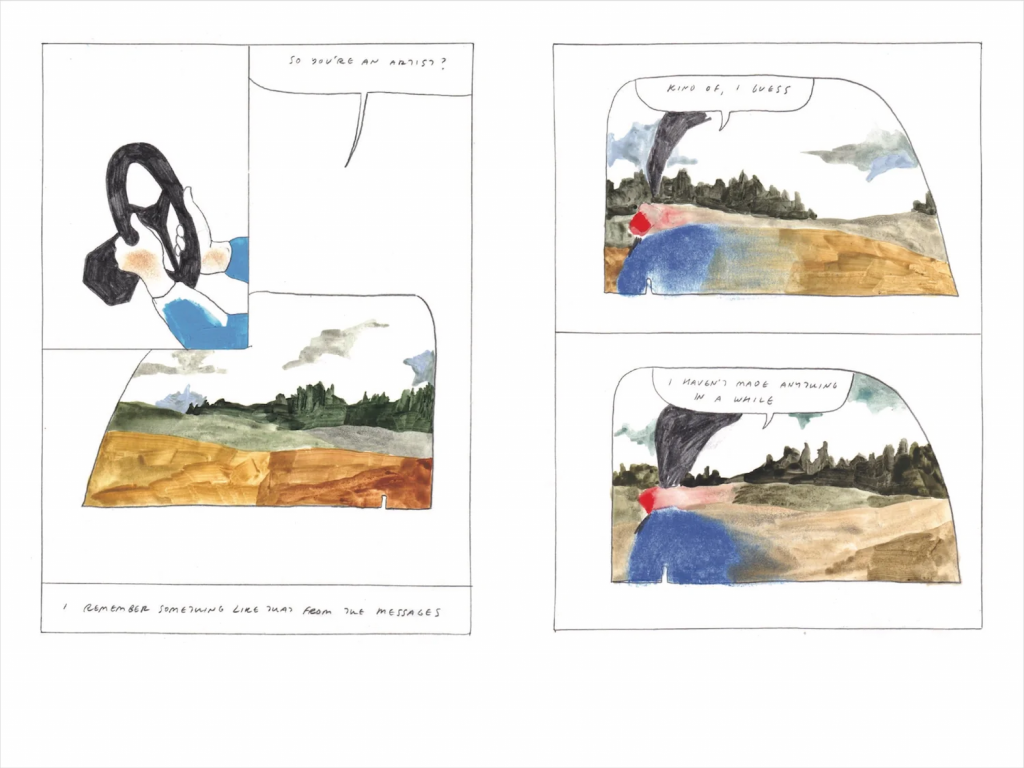

Toward the end of “Spiral,” the unnamed protagonist is in a car en route to her farm destination. We don’t see any detail of the car, of course; only the outline of the window, and the vistas on the other side of it. The protagonist’s reflection in the window fades to the point of near nonexistence, losing herself in the views before her; she is finally pulled back into the “moment” as the owner of the farm asks the artist if she might help initiate an artistic project: her self — both visual and figurative — restored through common purpose. Artistically, this is Koch at her best: her application of lighting, the tenderness of her pencil strokes against the vibrancy of her watercolors. Metaphorically, this may as well be the thesis statement to the entire stage of her work that Spiral and Other Stories embodies: there is, patently, a world outside of the self — but is there really any point to the self, outside of its existence within the world?

Some years into my crisis of faith, I still haven’t found out what God means; it’s increasingly likely that I never will. However, I have learned to recognize the artists that are on a similar journey of open-ended learning. Michael DeForge comes to mind here; so does Brian Wilson, and if you don’t believe me all you have to do is listen to the intro to “California Girls” and tell me that such a gorgeous piece of music could be written by a man who hasn’t seen the face of the Almighty.

Usually, these artists don’t limit themselves to any one cosmogony or faith system; their gestures go beyond the act of mere naming. With Spiral and Other Stories, Aidan Koch expertly inserts herself into this category of spirit. The power of things left unsaid is sustained here, with an enhancement: the acknowledgment that somethings cannot, in truth, be said, only gestured toward in almost free-form watercolor. But they can damn well be felt if you leave yourself open to it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.