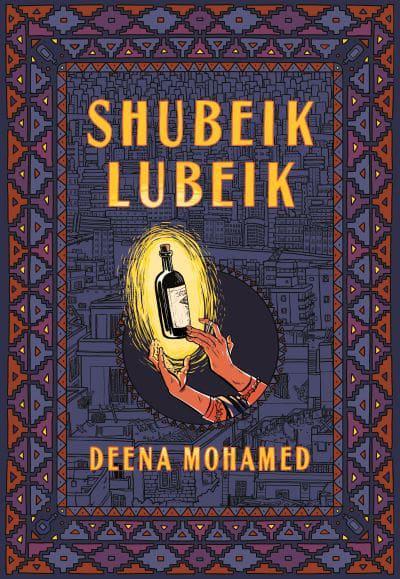

The idea of wishing is central to Shubeik Lubeik, as the title of Deena Mohamed’s latest work can be translated as “your wish is my command.” Though Mohamed has said in interviews that she began this work with the idea of the kiosk and the importance it plays in Cairo culture, wishes serve as the center of the work. Mohamed imagines a world where people can purchase wishes, though not all wishes are equal. Instead, there are three classes of wishes, ranging from the first-class wishes which are the most expensive, but also most reliable and powerful, to the third-class wishes which are the cheapest, but often misinterpret people’s wishes, sometimes leading to great harm.

The plot centers around Shokry, a kiosk owner, who has three first-class wishes, despite his lack of socioeconomic status. The reader ultimately finds out how he has them, but he lets people know early on that he doesn’t want the wishes. Instead, he puts up a sign to sell them for much cheaper than people could get them elsewhere solely to rid himself of them. Shokry essentially frames the overall work, as Mohamed originally wrote the three stories that make up this work as separate tales. In this collection, the reader sees Shokry sell one wish to Aziza, one to Nour, then try to decide how to use the final one himself.

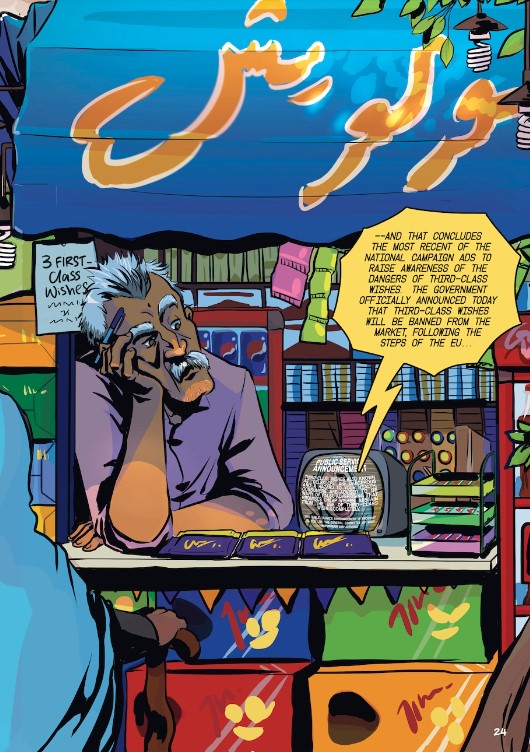

The art follows this structure, as the frame story of Shokry is in vivid colors that convey Shokry’s interactions with Shawqia, a woman who often visits the kiosk and who becomes important in the third section of the book. When the work shifts to the individual stories of Aziza, Nour, and Shokry (as a person who has a wish), Mohamad shifts to a detailed black and white palette, where she makes wonderful use of dark ink and strong contrasts. These contrasts work especially well in the Nour section, as he often feels separate from the people around him. Throughout the black and white sections, Mohamad also uses a recurring full-page spread to show what stands in the way of the character using the wish. On one side is an exaggerated picture of the bottled wish, while the character is on the other, with whatever obstacle laid out between the two. Mohamad also intersperses infographics from a company called The Wishes for All Foundation that provides readers with more information on the wishes, with Mohamad’s recreation of such informational handouts spot on.

Each story tracks the character who has the wish and how they hope to use it. However, Mohamad spends significant time developing each of these characters to show not only how they came to Shokry’s kiosk and in need (or at least desiring) of a wish, but also how they have come to be the people they are. Since Mohamad begins Aziza and Nour’s stories before they seek the wish, the reader isn’t clear what they might want or need, simply reading their stories to know them first.

Aziza’s story tells of how she fell in love with her husband and what has happened in their relationship as they have gotten older. Their relationship goes back to childhood, explaining her husband Abdo’s fascination with wishes when she had no interest. When she ultimately does purchase the wish from Shokry, she is immediately accosted and arrested, as the police don’t believe a woman of her low socioeconomic status could have legally obtained a first-class wish. One of the police officers says to her, “I mean . . . who are you kidding? A first-class wish for someone like you? Come on, now!” She spends years in jail trying to prove her innocence, only to find out that the police were trying to wear her down, so she would give them her wish. People cannot steal wishes, as the owner has to give the wish away for it to work; thus, the police cannot take Aziza’s wish without her permission.

The core of her story, though, is love and forgiveness, as the reader finds out more about her and Abdo’s relationship during flashbacks while she is in jail. Mohamad ultimately conveys not simply the obvious reason why she wants the wish, but a deeper reason that speaks to Aziza and Abdo’s relationship as more nuanced than it first seemed. In fact, early in that story, one might wonder what Aziza sees in Abdo at all, though they will understand by the time she uses the wish.

Nour’s story begins with their hanging out with their friends and discovering Shokry’s kiosk by chance as they are walking by. They’re amazed that Shokry could have a first-class wish to sell, so they stop and check out its validity (there’s a complex licensing system to make sure wishes are valid, but also to keep them in the hands of those who should have them, according to the government). While Nour’s life seems to be going well, as they’re in college and have friends, it becomes clear that Nour is struggling with depression that is so severe it keeps them in bed for weeks at a time. Nour, however, hides this depression from everybody in his life, lying to their parents and friends. When they do try to tell Adham, one of the friends Nour’s story begins with, Adham doesn’t believe depression is real: “I mean, it’s not a big deal. . . This is Egypt, you know? Depression is like first-world problems. Like if you just get some fresh air and exercise and eat well, you know . . . I dunno, like, I always feel like this kind of thing is so melodramatic and American, haha!” Nour has the wish at this point but knows better than to wish simply to be happy, even doing research to discover that this approach would give them a superficial state of happiness without changing their true state.

Nour has a friend who’s a psychology major, and she suggests a therapist for them, making it seem that they have a chance to have somebody hear their problems. The therapist seems to offer help when she confirms that Nour is depressed; however, she then suggests that Nour is responsible for their own depression. She says, “For example, maybe one of the reasons you’re depressed is because you feel isolated. Perhaps we could start with your appearance to help you reach a more ‘normal’ look . . . And discuss why you present yourself this way.” Mohamad keeps Nour’s gender vague, only having one of their friends refer to them as “they,” but it’s clear that the lack of acceptance others have for their presentation, society’s unwillingness to accept Nour’s gender identity, exacerbates Nour’s depression. Mohamad explores the idea that Egyptian culture doesn’t accept depression as a legitimate disease and that the rigid gender norms of that culture also alienate those who don’t fit the clear binary. Nour ultimately finds a therapist who can help them, but Nour still uses the wish once they better understand themselves and why they’re suffering.

Shokry’s story doesn’t seem to center on him, as his plan for the remaining wish is as a gift to Shawqia, the woman who visits the kiosk in the colorful frame tale. The reader thus gets her backstory, as she explains to Shokry why she doesn’t want the wish, even though she’s dying of cancer and clearly loves her family and friends. However, much of this section details Shokry’s backstory and how he came to have the wishes at all. His main conflict is that he is Muslim, and he believes his religion forbids him from using wishes, that it is haram. He believes he can give the wish to Shawqia because she’s a Christian and has no such limitations. Shokry even watches old videos of a sheikh who railed against using the wishes, pushing back against his granddaughter who shows him videos of new scholars who question that interpretation.

Ultimately, Shokry’s story is about this question of doing what is helpful when one doesn’t believe it’s right, at least according to one’s religious worldview. Shokry has spent his entire life being too generous, trying to help everyone in need he came into contact with. In one scene, he is speaking to a friend, but also texting donations that are being advertised on a billboard behind him. His friend comments, “You’re always taking responsibility for things that don’t really concern you. . . . You don’t need to help everyone under the sun! Let people handle their own issues!” Now, though, he feels he has a chance to truly help somebody, but his religion forbids him from doing so. He ultimately has to learn the central truth of Islam to know how to act and what to do with the wish that he feels has haunted him for years.

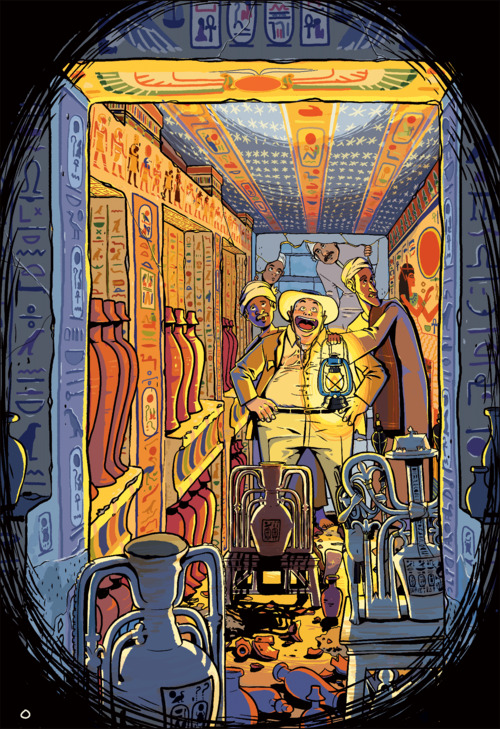

Mohamad uses these wishes as metaphors for contemporary issues facing Egypt and the twenty-first-century world. She presents the discovery of wishes as similar to the discovery of fossil fuels and other resources, as many are located in the Middle East, and characters even refer to these locations as wish mines. These discoveries lead to the same type of colonialism and exploitation that other discoveries of minerals and resources have, as the West comes in and takes the wishes, leaving the locals with little more than third-class wishes with ill effects. One of the informational sheets from The Wishes for All Foundation shows a map with the mines mainly located in Africa and the Middle East, while the refineries are primarily in the US, UK, Russia, and China. As with contemporary globalization, the wealthier countries take the resources away from their location and use them for their own profit.

Given the levels of wishes, it’s no surprise that classism is a thread that runs throughout all of the stories. Only Nour comes from a middle- to upper-class background, as he’s easily able to buy the wish. Aziza, though, has to work for several years to be able to afford even Shokry’s reduced rate, and Shawqia seems to be middle-class at best. Aziza and Abdo’s story provides the best example of this stratification, as Abdo spends his childhood trying to use a third-class wish to get a Mercedes and Aziza is arrested under the pretense that she could never afford a first-class wish, and, thus, must have stolen it.

That stratification leads to wish abolitionists who believe the entire system should be dismantled. In the same way that contemporary abolitionists wish to rid the world of fossil fuels or cobalt mining, wish abolitionists want to get rid of wishes altogether. However, their reasons are slightly different, in that every time somebody uses a wish, the djinn has to grant that wish. One of Nour’s professors argues that all wishes are problematic, then, as “in both cases we are essentially forcing these powerful sentient beings to serve us and selling them as products.” Thus, these abolitionists seem in line with those who worked for the abolition of slavery, while there are the other echoes of slave labor to mine the wishes.

Mohamad’s work makes great use of this metaphor and the storylines she weaves them through, raising questions about contemporary Egyptians and the roles Egypt and those who exploit the country and area play on the global scale. The stories are compelling in and of themselves, but the questions Mohamad raises about exploitation, mental health, religion, forgiveness, and love enable the reader to care for the characters while caring about the world.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply