Ivana Filipovich began her career in comics twice: first in 1994, in her native Serbia (then part of Yugoslavia), where she enjoyed some success writing and drawing short comics for arts and literature magazines; then in 2017, eighteen years after escaping her war-torn birth country for Canada and taking an extended break from comics. In 2022 she released, on a print-on-demand model, her self-published short story collection Where have you been?,a restless, anxious package whose craft is as poignant as it is atmospheric. While she sometimes writes about her home country, her priority is the wider human pursuit, whether set in Serbia or in Canada, and she realizes a wide range of emotions with an almost impossible clarity. I had the pleasure of speaking with Filipovich over email, starting in late May and ending in July, as we discussed comics as craft and business and art as a result of influences internal and external. Any hyperlinks included in the conversation are Filipovich’s own additions, for context and further reading. This conversation has been edited for flow and legibility.

—

Can you describe what the comics landscape in Yugoslavia was like when you first got into comics?

I started reading comics as a kid. The first ones I saw were the ones my father confiscated at work from the staff that read them on the night shift at the factory. Those Italian-made comics are still popular in the Balkans today—fake Westerns and other American-themed series like Zagor, Il Grande Blek, Comandante Mark, and others. The newspaper ladies scoffed at me when I asked for comics. I don’t think they would have derided me as much if I had asked for romantic novels. Soon I graduated to comic art magazines and got familiar with the Franco-Belgian and Latin American comic art scene, from Moebius to Hermann and Breccia, which was more intellectually stimulating and visually appealing. Through all that searching in the dark, I landed on Hugo Pratt and his comics, which are still my favourites.

I only got acquainted with the Yugoslav comic arts when I went to study in Belgrade. In the 80s, there were a lot of phenomenal Yugoslav artists, like Mirko Ilić and Igor Kordej. Sometimes in the 90s, I decided I could do something myself. It was a product of thinking about my skillset and what makes sense, so I fused my literary ambitions with my drawing skills. I was fortunate to run into supportive editors and cartoonists who were happy to advise me and publish my work. Everything I have ever made, except for a few unfinished pages, was published. But, by then, things were falling apart in the country, and the publishing industry and comic art and literary magazines where I could publish short stories, which is my preferred format, started to fold one by one. The Balkans still have a very strong comic art scene, with many cartoonists, like Zoran Janjetov, working for the French market, unfortunately only as cartoonists but not writers, so I feel a lot of talent is wasted. From my generation, only a few auteurs escaped that fate, like Aleksandar Zograf and Danilo Milosev Wostok.

Looking back at that time, I was lucky to have been exposed to the best the world’s culture offers, from BBC programs to obscure writers like Daniil Kharms. Former Yugoslavia was quite open to worldwide influences. In comparison, Canada feels like a closed, isolationist society. I live in British Columbia, and we don’t even get to watch Quebecois productions on TV. I’d seen more of those before I moved to Canada. During the pandemic, I saw the first subtitled TV show on American Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). There is an aversion to subtitles, I guess. Returning to your question, I was more influenced by classical and modern literature than comics. Nevertheless, the Yugoslavian comic art scene was and is very inspiring, and the area still produces outstanding works of comic art.

From Overture (1994, updated in 1999)

I suspect a lot of people, certainly like myself, don’t really know much about the Yugoslav and Balkan scenes beyond a few names. Kordej, Macan, Biuković – the names that made it to the Anglosphere, basically. It’s also interesting that you say you are more influenced by literature than comics, because when I read Where have you been? my first reaction was definitely “okay, this feels different,” in a good way – it was clear that your priorities were not just to repeat what was going on around you, artistically speaking. You mentioned that basically everything you’ve ever made, or finished, was published. How did the first publishing opportunity come about? Was that your story in Tron [Serbian for Throne] #6?

Before comics, I worked as an illustrator and designer. I published a few illustrations in zines and student papers and worked as a poster designer for the popular student club KST (Engineering Students’ Club) while studying architecture. The club is in the basement of our school, and a few of us from that generation worked for them as designers. We almost got fired, as our posters were so popular they’d get stolen as soon as they were put up. Most of us left architecture to work as designers professionally. There was talent in abundance!

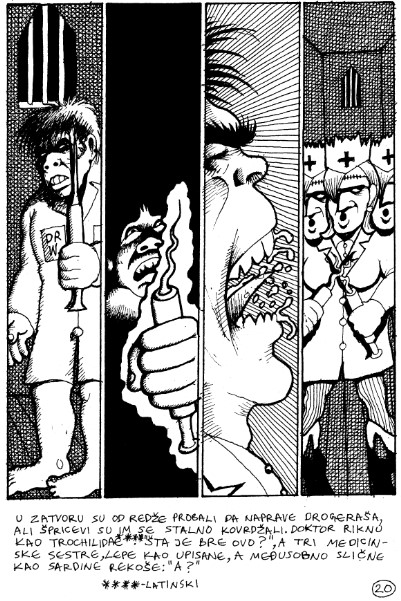

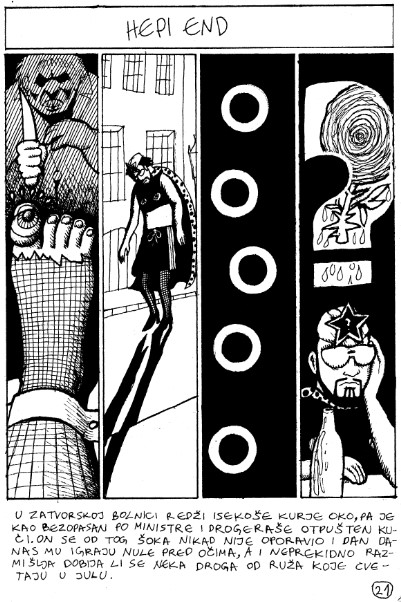

Through an architecture job, I met a woman whose husband has helped many aspiring cartoonists. Vladimir Vesović still teaches cartooning in Belgrade, and the school just celebrated its 30th anniversary. He was a co-editor of Tron magazine, and he and Boban Savić immediately offered to publish something of mine. The Overture was created and published in #6 in 1994. Both were very supportive and didn’t make any corrections or edits. They immediately asked me for a comic serial, and I started publishing the Haute couture comic, but unfortunately, the magazine folded. That comic has a female character that changes outfits non-stop, as a reaction to the common way of sticking to one recognizable outfit.

The version of The Overture included in my collection is a newer one, drawn in 1999, to make it stylistically closer to my later style. The original version was done with a brush.

In the foreword to Where have you been? Vasa Pavković describes you as sort of an unusual contributor to Tron, given that you worked alone and in a different genre and aesthetic. Did you feel out of place at all? How was your work received at the time?

I didn’t feel out of place because we had Stripoteka magazine, which was publishing comics from all eras and from all over the world. You’d have Conan the Barbarian and Corto Maltese side-by-side. I’d flip through it, and suddenly, there would be a shining diamond, something totally unexpected. That magazine created an atmosphere of enjoying comics indiscriminately by mixing high-brow and low-brow. We also created interesting pairings amongst ourselves. For example, I collaborated with the alternative artist Danilo Milosev Wostok to create a political comic, Corkscrew against Dope. We bonded over Hüsker Dü music and a shared sense of humour.

My experience of entering the scene was very positive. I had a lot of support from editors, colleagues and festival organizers. Vasa Pavković invited me to publish in the literary magazine Reč [Serbian for Word], where True Story, Marilyn, and A Real Nightmare [all short stories included in Where have you been?] were first published.

From This or That? (1997)

It sounds like there was a lot of camaraderie in the scene, which is heartening to hear. I wasn’t familiar with Corkscrew, but I’m curious about how you approached collaboration for that, since your work is so defined by the singularity of visual and narrative voice. How did you and Danilo approach that piece?

I wrote the script, the story of an alcoholic superhero fighting the drug trade, and gave Danilo complete freedom of interpretation. He vastly improved the script by adding visual references that didn’t even cross my mind. Those references made the story even more layered and fun. For people reading between the lines, the story clearly skewers politicians involved in the illegal drug trade to support the war in the Balkans.

Was that the only time you’ve collaborated on a comic?

No, there were other collaborations, but not as extensive as this one. Mostly a page or two. Some were at various festival events. One old collaboration ended up on a shortlist of Angoulême 2022 in the alternative comics category, as it was finally published. My page from it is posted on Instagram. I am currently participating in a large project by the writer Marko Stojanović, which connects numerous artists across the Balkans who work on individual pages from his script.

Did collaborating change the way you’ve approached your solo comics?

I like solving problems, and collaborations can be like that. With free-flowing storylines of collaborative comics, you can always spin the story in an unexpected direction. In the project with Wostok, it was fascinating to see what he thought the script was about and how he presented it. There was nothing cliché about it, and he made cultural references I didn’t think of. But you’d have to be erudite like him to pull it off. Even when I give people my working scripts to read, I sometimes get surprised by what they get from them. There are a million things people will think of and associate with even the most straightforward descriptions. I’ve always liked absurdist literature and that element of surprise, and I try to think of something unexpected that can improve the storyline.

Yeah, I definitely know what you mean. I’m only a writer, so whenever I hand a script to my artist there’s always the excitement and pleasure of seeing how they read it and what they add to it. Is it okay to ask about your time in Serbia during the Kosovo War? I would love to hear about that but obviously only if you’re comfortable sharing.

Sure, I have no problem with that.

From To Be Continued (1995, updated in 2019)

What prompted your decision to finally leave the country during the war? Was there any event in particular that made you think “I have to get out of here”?

Things were getting progressively worse over the years, and political protests were not getting results. I remember seeing Slobodan Milošević for the first time. It was the historic live television broadcast of the Eighth Meeting of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Belgrade in September of 1987, and Dragiša Pavlović was speaking. Behind him was this figure looking down on everybody, like looking at bugs, his lips crooked. I thought to myself, This is not good. My parents were communists, but I rejected any connection to it. My father watched with me but didn’t comment, and he was the Communist party leader in our town. I couldn’t understand why nobody wanted to say anything. It stayed with me for a long time, that image. It was the moment to stop Milošević, and we all missed it.

The result of people trying to isolate themselves from problems and not voting in elections for absolutely everything is the situation we have all over the world. And this applies to artists, cartoonists as well. The best [advice for] your art is not to draw more. It’s to get involved with organizing, participating in the political process. For example, vote for parties that support arts and culture and will provide funding. Get on juries for art competitions or Canada Arts Council. Lobby to get comics included in writing competitions, and back into media outlets from which almost all editorial cartoonists were expelled.

In Serbia, we allowed nitwits and downright criminal individuals to lead us. I fear for world democracy in the same way as I worried for Yugoslav society in the 90s. The former UN human rights chief Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein was interviewed by CBC, when he point-blank said that idiots lead us, and it’s a world problem.

I had a little bit of money, and I was thinking about what was best to do at that point in my life: pay to continue my studies to become an architect-archaeologist or do something else. It was the first time I was required to pay for my studies in former Yugoslavia. Up until that point, higher education was free. I literally turned away from the cashier and went to the Canadian embassy to pay for a self-financed emigration visa. So, it was a confluence of things. A realization that to win against a much stronger and more vicious opponent, at some point, you have to get into that fight that has harsh personal consequences or leave. I felt unable to use violence, and it was getting to that point.

Did you leave Serbia alone, or did anyone come with you?

I left alone.

Did you have any contact with your community after you’d left?

You mean the cartoonists?

Both the creative community and personal social circles.

I kept in touch with all of my circles and saw some of them once in a while when I went back to visit my parents. I was reading news from that area for a few years after I left, and then stopped and started really focusing on Canada. Now I follow media from both again. Things got even easier with social media and I started getting invitations to publish in various magazines through social media as well. There is a slightly different approach: here you are supposed to pitch publishers, but back in the Balkans, they are actively searching for talent and reaching out to you. This applies to both paid and unpaid opportunities. But there are exceptions. Pia Guerra told me she got contacted by the Washington Post, after her Trump cartoon went viral on Twitter, which is fantastic to hear.

From What’s fear got to do with it? (1999)

Yeah, social media has definitely been a wonder in that regard. I’d love to hear more about how the internet has impacted your artistic experience over the years; I realize that social media as we now know it was not around for the decade-plus-change of your work.

More connected, but alone? I stayed away from social media for a long time, but it became necessary. The most enjoyable element is seeing wonderful art and connecting with those artists in the virtual environment, if nothing else, to say you really appreciate them and their work. I constantly take screenshots on my phone of inspiring art and comic books I want to read. Recently I saw work that blew my mind by the French illustrator Georges Beuville, thanks to some French cartoonists I am following. It made me realize that he probably influenced cartoonist Paul Gillon, who used to be my favourite artist. I discovered Mean Girls Club by Ryan Heshka when Mirko Ilić posted about it.

At the same time, there is more and more garbage online, and it’s difficult to sift through. I’ll soon have to limit my research to university libraries.

Yeah, a lot of that rings true. I can definitely say for myself that the vast majority of my favorite comics at the moment are ones that I would not have discovered if not for social media. Plus, social media is the way I found out about your work, so no complaints there [laughs]. I’d love to hear about your move to Canada. According to the notes in Where have you been? I understand that you were basically on an extended hiatus from making comics from 2000 until 2017. What can you tell me about those years off?

Once I arrived in Canada, I connected with some cartoonists and publishers. One respectable publisher wanted to publish a book of my short stories but wanted me to redraw everything again in the same style. That’s why the version of Overture in the book is newer, not the original one. At some point, I said to myself, This is silly and stopped. The field was already in free-fall, and the cartoonists I spoke with told me about their issues. Low pay, juggling multiple jobs to make ends meet. Coming from an area with a decade of sanctions and high inflation and having starved for a while, I just wanted a normal life. Self-financing immigrants must quickly decide what to do and how to support themselves, as there is no safety net for them here. Architecture is different in British Columbia, and it was never fun for me to begin with, so I started working as a designer. The country doesn’t need architects-archaeologists. One thing led to another, and I got a very high position at an educational media unit at a university. That was a lot of work, so I abandoned comics. To be honest, it was painful. That’s why I had to stop even reading comics and graphic novels.

Did you not engage with comics at all, as a reader or a creator, for all of those years?

No, I read very few comics or graphic novels, mostly by friends. I started reading again in 2017 when I decided to start making them again.

From My Former Boyfriend (2017)

What led you to take them up after all those years? Was that something you’d always intended or wanted to do, or were comics something you’d already put behind you?

I had all these stories wanting to come out, and I started feeling like I had to do something. My decision to stop writing didn’t stop my brain from spinning stories. It never stops working and looking for stories.

Did it take any adjustment, getting back into the process, or did it come back naturally?

Writing came easily, while other things were swinging in unpredictable ways. One drawing would be easy and good, and another, total garbage. The biggest problem was motivation and getting enough published comics to regain my confidence. To work on comics while maintaining a highly demanding professional career at a university is challenging, to say the least. But many cartoonists have to juggle multiple jobs nowadays, and they manage. This is also another way in which social media came in handy. I started following a lot of artists who have been vocal about their struggles, and it was helpful to see that they complain but persevere. And it’s not like you always want to work on the comic at hand. I’d be really aching to paint, but I’d have to work on a comic. It really becomes a job, and there is no time off. So, having a routine is critical. All other elements fall in place eventually.

After getting rejected by a small West Coast anthology, I almost dropped everything. Luckily I decided to run the script by some friends who are published literary authors, and they loved it and encouraged me to continue. Another big confidence booster was receiving invitations from Serbian publishers. And I found a very nice Swedish group, C’est Bon Kultur, which regularly posts calls for international anthologies. Participating in their calls gave me deadlines and themes to work with and pushed me to do many new works. Without it, the collection of comics and my late comics career resurgence would not have happened.

I’d love to hear more about how you approach writing, in particular, because what I found striking about your collection is the way that a lot of the narratives emerged from that general air of discomfort and restlessness; you didn’t prioritize atmosphere, so to speak, but it is certainly a driving force in your narratives.

In most cases, the largest and longest portion of my process is the creation of characters. Who are they, what drives them? Basically, their psychological profile and biography. It doesn’t necessarily include any story writing, but it’s very helpful. I usually start drawing once I am happy with the script, which kicks around my brain for a while before I record it. And there is a strict process of rewriting and cutting out, as much as possible, until there is just enough for the reader to form the story in their own mind. And that continues until the last moment before I submit it for publishing. That’s the luxury of the author who doesn’t depend on this for a living or is working with smaller publishers who do not have an inflexible process. There is a very useful book, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, by Stephen King. If you skip the biographical part, it’s not very long and offers no-nonsense advice I agree with. As a big fan of Chekhov, I read his letters and his advice to other writers. Don’t write “the sky is blue”; we all know that. And think about how to divorce images from text to improve storytelling. I mean, I am far from being happy with my own art, and I think there is a lot I need to improve in terms of pacing, sequencing, and visual storytelling in general, as most of my storytelling gets a hell of a tempo as I rush through it. But at least I am aware of it.

From My Neighbour from Haiti (2018)

There is a sharp stylistic contrast between your early stories and your more recent work, going from scratchier, more delicate and precise pen-work to an inkier, more fluid brush look. How have you perceived your evolution as a creator over the years?

Yes, gone are my rapidograph days! I learned all about these nifty tools in high school, and for consistent line art with waterproof inks, still the best. They sure last a lifetime if you keep them in good working order. I feel like I am still searching for a signature style, but I also want the flexibility to use a style that works for a specific comic. Especially for short comics, I don’t see why I should limit myself to one style. It’s like telling a film director to always shoot the same movie. And I’d like to loosen up more. As I like to say it: stop drawing eyelashes.

Throughout my comic art career, I’ve been trying to speed up the process, so I’ve been an eager adopter of new technologies. Hearing some creators spending decades on their graphic novels, like Seth on Clyde Fans, fills me with awe, but that’s not me. I am impatient, and I lose interest quickly. After doing My Former Boyfriend and My Neighbour from Haiti in acrylic and ink and 14 Marauders in pencil, I switched to iPad and Procreate and never looked back. A couple of first tries were a disaster, but I needed to adapt scenes and reorder quickly, so I preserved, and now I feel very comfortable using Procreate. I still press like a maniac for no reason; I hope I don’t kill that iPad. My handwriting is horrible now, so I am happy to use fonts based on my earlier handwriting. It could be better, but I’d rather see something finished than not done at all. Kill me, but don’t ask me to do lettering!

When I received my copy of the book, I couldn’t help but notice that Where have you been? is sold on a print-on-demand basis. What prompted your decision to go with that model?

My original idea was to print it locally, either in BC or somewhere in Canada. I work at a university, so I tried to access services available for university printing needs, which are as inexpensive as possible. It was at the start of the issues with paper supplies due to COVID disruptions. It turned out that printing it locally in small quantities (less than 500 copies) was too pricey, especially because cheaper paper was unavailable. The test books were also too bulky for shipping as letter mail. I don’t particularly like financing Jeff Bezos’ space dreams and other escapades, but Amazon print-on-demand is more environmentally friendly (as far as I understand the process), as it prints the book in the area where the order is going. Since they print books in the same formats and digitally, it adds your book to a queue of other orders. So, if you ordered from Amazon Germany, it’s supposed to print there and ship at a short distance. All things considered, for an unknown author without a big audience and no ability to fulfill orders, it was the best solution to have a book available worldwide. For this book, earnings were not a big consideration. I think of it as a “loss leader.”

One notable thing about Where have you been? is the numerous stories that you went back and revised or updated, either in the ’90s or twenty years later; even in one of the stories that isn’t said to be updated, made in 1999, you reference Netflix and Instagram. What is your approach to revisions or retroactive changes?

Almost all older stories in Where have you been? are slightly revised for one reason or another. Since it’s a collection of comics I put together and self-published, I used the opportunity to iron out some kinks. For me, it’s hard to look at something at such a distance and not make at least some changes. Plus, some of my stories I had accessible here in Canada were only in early English translations, so I had to recreate some of the content from memory.

The story What does fear have to do with it? was revised for publishing in the philosophy and culture magazine Apokoalipsa in 2019, but I forgot to include it. This particular story has been revised multiple times over the last few years, as it was still a work in progress. It’s been finally extended to a graphic novel and revised significantly yet again. It’s coming out this fall through Conundrum Press.

I am one of those types who fiddle with dialogue until something goes to press, and I take any opportunity I have to review and revise. After all, this book was meant as an introduction to North American audiences and publishers, and it made sense to make some changes. That said, I’ll probably revise my comics as long as I am alive, as I can’t let go. [Laughs]

Do you feel that this geographical change has affected your art? Was there a change in “priorities,” a need to adapt yourself artistically to the mode in Canada? Are there differences that you’ve noticed between the two geographical scenes?

I feel there is more pressure in Europe to produce high-quality art for comics. Moebius still looms large. But I like that things are a bit looser here, especially for alternative comics. And I adore how, for example, Jillian Tamaki utilizes highly stylized to highly realistic styles without feeling she needs to constrain herself. In Europe, artists still have to stick to their signature style.

The main change for me is in the subject matter. I do slice-of-life comics, but the themes should be Canadian or North American to get any attention here, and that’s fair. My priority right now is to find a way to draw faster without losing the quality of expression.

You mentioned What’s fear got to do with it? which will be published as a graphic novel this coming September. What about that particular story prompted you to revisit and revise it over the years?

This story was always supposed to be a graphic novel. I wrapped it up to be a 30-page story for my collection of short comics. It got the attention of Andy Brown from Conundrum Press, who thought it had a lot of potential. I agree with him that the characters are very strongly outlined, but at first, I wasn’t too excited to revisit them. I felt like I’d outgrown it, stylistically and story-wise, plus it had real drawing challenges. You know what I mean? Dressing Mia in leopard-print pants was a stupid idea, but her wardrobe of strong prints works for the character. It took me a while to figure out how to expand it and, at the same time, make the work enjoyable for myself. It only started to click once I threw out all notions of where and when the story was supposed to be situated. The first draft took the story past the original 30 pages. Then I thought to myself, Why? Why not go back in time and dive into the relationship between the three characters? I believe Andy commented along those lines too. Looking at it in its completed form now, it is a textbook exercise on dealing with story challenges. Now I feel I can teach a course on it!

From 14 Marauders (2019)

A theme that occasionally comes up in your work is the lasting collective and personal impact of living under a dictatorship. How do you perceive the role or function of art when dealing with this type of subject matter? Do you approach it from a point of personal catharsis, the release of being able to say things now that in real time would pose a real risk against the authorities, or out of a sense of political urgency?

Interesting that you picked that from my comics. My primary interest is human drama and moral corruption, and everything else is the background. Having lived through communism and Milošević’s rule, I feel that I was freer to express myself back then and not put myself and my publishers in the Balkans at risk. It was not an issue to depict a bisexual character or criticize the connection between police, politicians, and the criminal underworld and have those comics published. My impression from afar is that in the last decade or so, Serbian society has become ultraconservative, violent at the personal level, and completely paranoid. This is probably shocking to you, but during Milošević’s rule, he and his henchmen only dealt with the people who were most dangerous to him and left the rest of us more or less free to do whatever we wanted. Comedy, editorial cartooning, literature, and other arts were flourishing while criticizing him, without him or his party batting an eye. While today, an alternative comic art show can be smashed up, and cartoonists like the legendary Dušan Petričić (who spent some time living in Canada) can be harassed and removed from social media. Granted, our world is more online now, and we could be tracked down. Today, it’s death by a thousand cuts, and every citizen of Serbia can expect to be harassed for their opinion by thousands of paid so-called (human) bots who sit in public sector positions whose job is to write positively about Aleksandar Vučić’s government and take down everybody else. I’d say today’s Serbia is a dystopian nightmare, and even my peaceful friends can experience threats of violence for posting a different opinion online. The current regime is more cunning and doesn’t necessarily execute prominent political opponents, but it makes it very risky for any individual to say anything. Harrasers like to say, “I know where you live.” So, it’s a conundrum for me at the moment. North American publishers are not necessarily interested in stories featuring flashes of Balkan politics, while the ones in the Balkans could be risking everything by publishing or exhibiting an innocent story about an LGBTQ+ character.

I suspect that, when it comes to the broad manifestations of dictatorship, many people, like myself, think, for example, of Argentina during the ’70s or of the Soviet Union’s constant surveillance, so the relative freedom of Milošević-era Yugoslavia is a very interesting contrast to the typical view of media resistance.

Artists cannot affect politics more than plumbers can. We hold a mirror to society, but the responsibility is wider and should be exercised by engaging in the political process at every level and casting your vote at every opportunity, from federal elections to restaurant awards. There isn’t any other way to bring about change. So, I try to tell the best, most impactful story I can about people living through some personal or societal ordeal.

From the titular story Where have you been? (2019)

From the outside, it looks like you’re not only always working but always sort of rethinking your past approach to your work and looking to adapt yourself. Is there anything that you are striving toward in particular? Is there any particular goal, or is the goal simply “forward?”

Immigrants must be adaptable and creative thinkers if they want to survive. It broadly applies to all, but especially to people who sometimes have nothing to fall back onto or don’t want to go back. I started my Canadian adventure as a “fashion advisor,” which is a fancy term for a salesperson at a high-end retailer, matching shoes, bags, and scarves for rich fashionistas without taste. You know what? It’s an experience rich with themes of exploitation, sexual predation, discrimination, and a demeaning hell. No experience is wasted on a writer, though.

Right now, I am thinking about what will be worth my time, what kind of graphic novel, and other engagements to do with the comic art scene. I think about what I can do to help other authors, as I would love to support the expansion of a thriving, supportive, and well-connected community here in BC. I hear we’ve been considered a Canadian comic arts backwater for the longest time. It’s simply not the case. There are very exciting artists living and creating in this area. As you get older, you also start thinking about your legacy and where you can make the most impact. All kinds of things come into play when thinking about my next graphic novel: why this story, why now, why am I the best person to tell it, where to publish, how to manage time, what style and techniques to use, where to get grants, what’s of interest to both North America and Europe, and most importantly, what can I be excited about as an author for a few years. It’s hard work. I have a glimmer of an answer at this point.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply