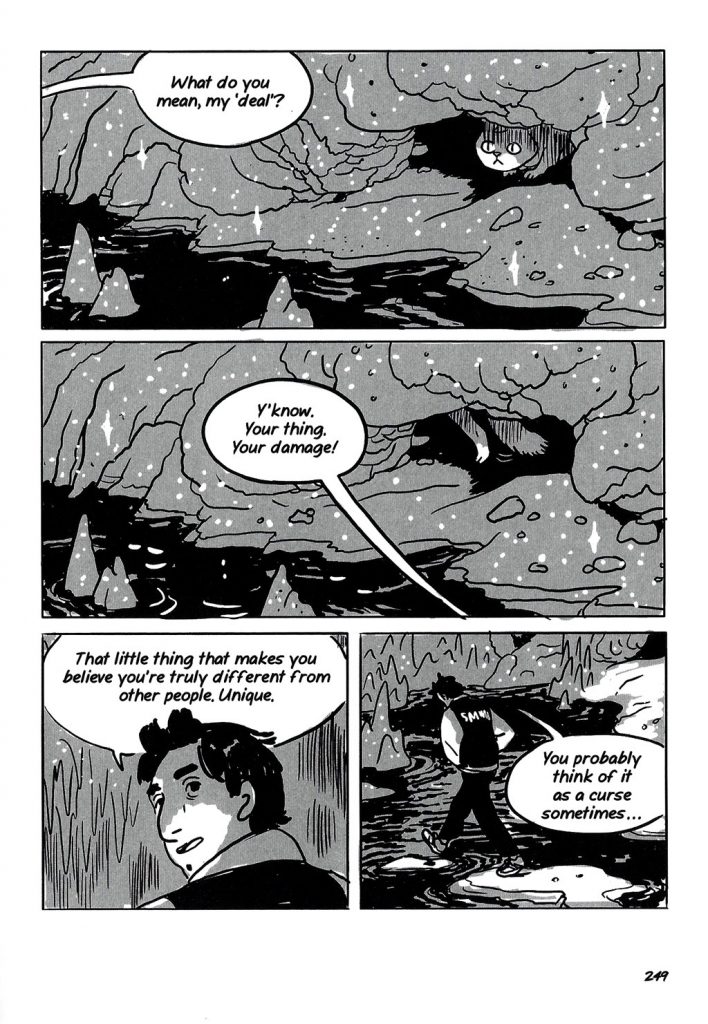

There is a beautiful moment towards the end of Jillian Tamaki’s webcomic Supermutant Magic Academy in which Marsha, one of the main characters, is asked by the school sports captain Cheddar what her “damage” is. It is the evening of their graduation party, and both have separately snuck off to a cave in the hopes of escaping the commotion. Asked what exactly he means, Cheddar specifies: “That little thing that makes you believe you’re truly different from other people […] You probably think of it as a curse sometimes … but deep down you believe it will be your salvation and the key to your ultimate triumph.”

Like many passages of Tamaki’s comic, the exchange is coated with a layer of irony and echoes the story’s many pop-cultural influences that it wears on its sleeve. Still, Cheddar’s question resonates with me. Maybe because it implies that we are all impacted or “damaged” by the world in certain ways and that we live with those impacts as best we can – perhaps even turning them into something positive. The passage makes me think about what it means to grow up and no longer be a child. If someone asked me when I think my own childhood ended, I would point to those moments where I became aware of my personal “damage” and to the pain I felt when the world as I imagined it collided with the world of experience. As I will argue here, few cartoonists have explored what it means to exit childhood as profoundly as Japanese manga artist Taiyō Matsumoto.

My first contact with Matsumoto’s work was as a teenager through the anime Tekkonkinkreet, which I saw a couple of years after its release in 2006. The science fiction film, directed by US filmmaker Michael Arias and based on Matsumoto’s manga of the same name, follows the orphan brothers Kuro and Shiro who struggle through daily life in a gigantic metropolis called Takara Town while fighting both violent gangs and a mysterious organization that wishes to turn the city into an amusement park. As a teen, I was awestruck by the unusual art style which differed from what I had come to expect from Japanese animation. Also, I was disturbed by the movie’s depictions of violence. The bloodshed on screen was different from the mindless fisticuffs of a standard blockbuster; I sensed that there was something delicate behind the science fiction veneer. By coincidence, I would later intern for Cross Cult, the publisher that released the first German edition of the manga Tekkonkinkreet, originally serialized in Japan from 1993 to 1994. Holding film and manga side by side, I would argue that the movie is an accomplished adaptation, translating the best of Matsumoto’s art – his eclectic, almost nervous linework, the expressiveness of his unusual characters – for the screen. The Takara Town of the manga, rendered through angular shapes with only sparse depth added with raster foil, is fully colored in the motion picture and becomes a place that seems almost tangible.

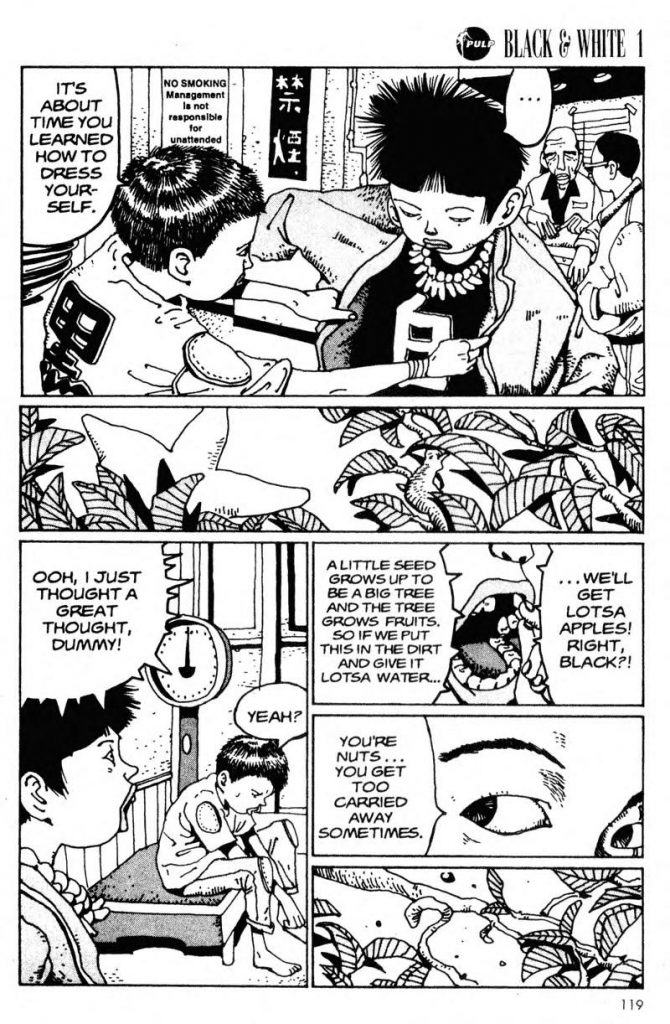

Most importantly, the film preserves what is without a doubt the beating heart of the story: the relationship between the two brothers. Frequently referred to as “cats” by the other characters, the orphans Kuro and Shiro are gifted with superpowers, including flight and extreme strength, which they use to lead an outlaw life by scavenging and stealing money. Of the two, Kuro is the elder brother who is more somber and self-reflexive, having one foot in adolescence. He tries to take care of Shiro whose naivete and playfulness clearly mark him as a child. As the conflict escalates between local gangs of Takara town and more sinister criminal organizations, a rift emerges between the brothers: Kuro becomes drawn into the spiral of bloodshed and embittered by their outlaw life. His growing apathy and nihilism stand in contrast to the mind of his younger brother for whom the world is still magical and a playground for his imagination.

Within the world of Tekkonkinkreet, in which Takara Town serves as a canvas for the general alienating potential of urban environments, the separation of the two brothers represents a threat to the cosmic balance. Kuro eventually encounters Itachi, a bullheaded evil spirit said to be a herald of the apocalypse, who encourages Kuro to pursue his path of violence that estranges him from his brother. Beneath its supernatural elements, the manga invites a psychological reading in which the brothers represent two stages of cognitive development: Kuro’s growing awareness of himself and the social structures around him amplify his grief over the city’s brutality. His reaction is to replicate that violence outward, causing a vicious cycle. Shiro, on the other hand, has not yet lost his sense of wonder and humility. While engaged in antics and singing obscene songs on the street, he also showcases radical acts of optimism, such as planting an apple tree in the brothers’ hideout. From this perspective, the underlying question of the narrative is whether it is possible to grow up and survive in a troubled environment without losing a childlike sense of wonder and possibility. One can forgive Matsumoto’s manga that these metaphorical layers are a bit “on the nose” by acknowledging that Tekkonkinkreet is one of his earlier works. What makes the narrative stand out in the end are the unique characters and the superb art of the filmic adaptation.

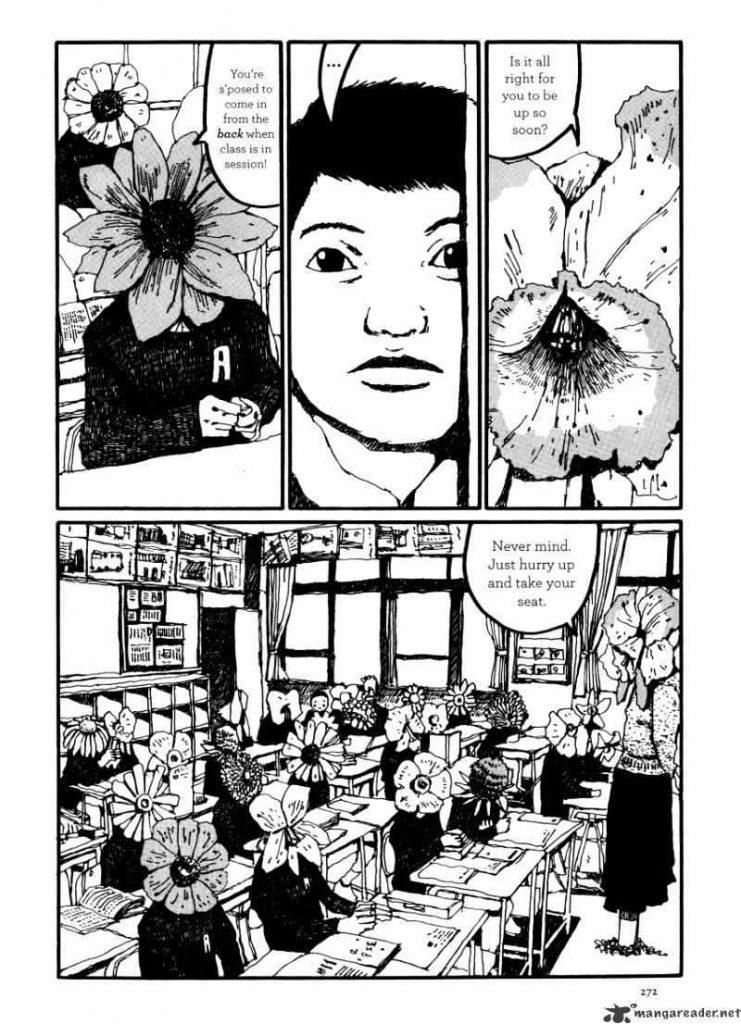

Six years after the conclusion of Tekkonkinkreet, Matsumoto would continue to explore the inner conflicts inherent in growing up, albeit through a vastly different genre lens. The manga Gogo Monster, released in the year 2000, also features child protagonists whose struggles with their environment are magnified to cosmic proportions. However, unlike Tekkonkinkreet which employs tropes of science fiction, Matsumoto takes a much more realistic approach in Gogo Monster by locating the conflict within the minds of its main characters. The story focuses on the second graders Yuki and Makoto who both visit the same school in urban Japan. From the very beginning, Yuki expresses his belief in a war between two factions of unnamed beings that only he can see, one of them inhabiting the school’s forbidden uppermost floor and led by “Superstar” whom Yuki views as an ally. Despite the manga’s suggestive title, these creatures are never clearly shown except as drawings by Yuki himself or as vague silhouettes glaring from cross-hatched shadows. Matsumoto instead uses detailed depictions of the school’s surroundings, of trees and the building itself, to convey a sense of premonition.

What first seems like the daydreams of a powerful imagination takes on a menacing edge in GogoMonster as Yuki is increasingly frustrated about the course of the “war” and because his peers label him as a dangerous outsider. An exception to this is Makoto who sympathizes with his classmate and curiously asks Yuki about the world which remains invisible to him. As the tension in the story rises, Yuki’s imagination becomes more and more disturbing as it encroaches upon his life as a student. In one sequence, he walks into the classroom to find the heads of his fellow students replaced by flowers, in another, the face of his teacher is facing the wrong way up. These scenes can be read as realistic depictions of an emerging psychosis, yet Matsumoto masterfully walks the line between psychological horror and a coming-of-age story by leaving the verdict open. Eventually, another outsider called IQ attempts to explain to Yuki that his mind is producing images on its own to avoid facing reality. Yet, this is the same person who is later trapped in the school building at night as GogoMonster hurtles towards its memorable finale.

These final chapters are what make Gogo Monster stand out as an artistic masterpiece. In the near-dark of Matsumoto’s drawings, moments unfold like delicate flowers. Their meaning is cryptic, yet, like shapes glimpsed through closed eyelids, they invite interpretation. As a recent practitioner of Zen Buddhism, I cannot help but see these final sequences as an artistic rendering of consciousness in the state of formation or dissolution. It is here that the art style of Gogo Monster fulfills its potential: The exceptionally thin and nervous lines and the intricate cross-hatching may be less strong in the depiction of characters, yet they masterfully bring to life the inanimate world, including the school building itself, its architecture and surrounding flora.

GogoMonster is clearly more focused on the creation of atmosphere than on the telling of a coherent story. Still, one can identify a dimension of social critique within the manga because it juxtaposes the rigidity of the Japanese school system and its pressures towards conformity with the behavior of outsiders Yuki and IQ. What stays in the dark, however, is the life of the characters at home. Like in Tekkonkinkreet, parents are suspiciously absent in the representation of the child protagonists which adds to a sense of their abandonment. This door would only be opened later by Matsumoto in the manga series Sunny, his most recent work to be discussed here.

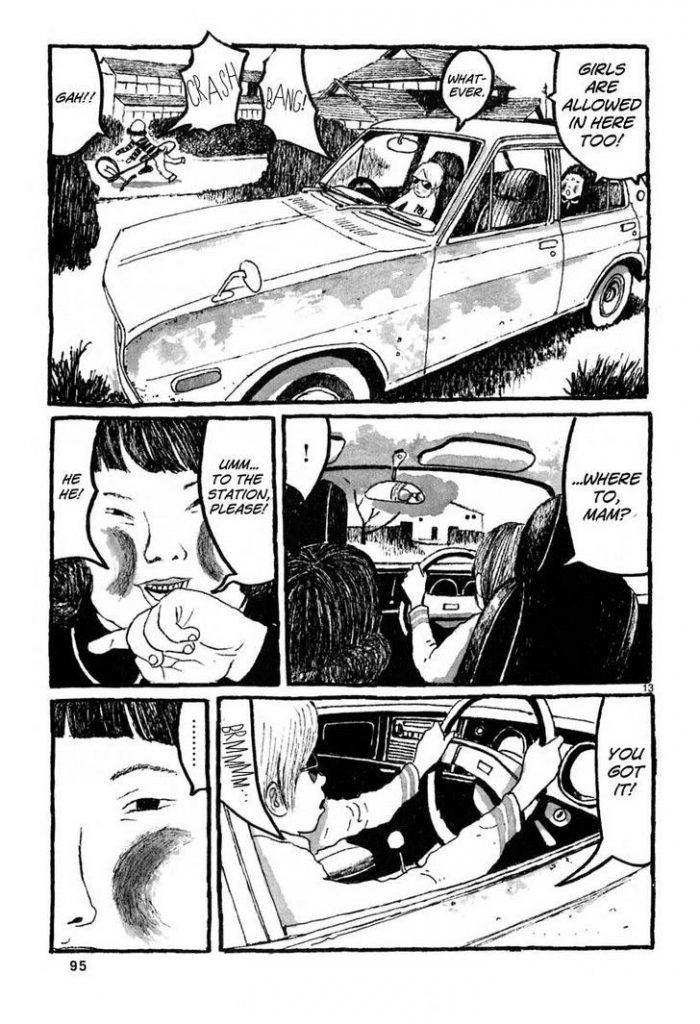

Originally serialized in Japan from 2010 until 2015, the slice-of-life manga Sunny depicts the inhabitants of a small group home and orphanage called Star Kids in rural Japan in the 1970s. The children have been given into care for various reasons, some due to the illness of a parent, others as the consequence of a divorce. The manga paints a warm picture of everyday life in the group home despite the unavoidable conflicts. Everyday bickering and group meetings over toilet flushing routines are shown just as much as moments of calm as characters engage in communal activities. The suspicion that Sunny may be romanticizing its subject, using the parentless children as some kind of metaphor, is dispelled by the melancholic undercurrent of the story. The saddest passages of Sunny are those in which its child protagonists let on that they are, on a certain level, aware of their own situation and that they struggle to differing degrees with the suspicion of being rejected by the world or their parents. In these dark moments, the children take refuge in an old Toyota Sunny, the manga’s titular vehicle which stands in the home’s yard and which is a “no-adult-zone”. The car, which is a visual parallel to the home of Kuro and Shiro in Tekkonkinkreet, serves as a magical portal, allowing the children to escape into imaginary worlds and to play pretend.

Sunny initially focuses on its boy protagonists Jun, Haruo, and Sei, whose differences and idiosyncrasies are the source of much entertainment. Jun, for instance, constantly has a runny nose and long fingernails while Sei is prim and proper, spending hours in the group bathroom combing his hair. While the narrative focus of Sunny later shifts to other characters, such as the girls Megumo and Kiiko, the boys stand out. In light of the specificity of the 1970s setting, it comes as no surprise that Sunny is autobiographically inspired: Matsumoto has revealed in interviews that he took inspiration from his own sojourn in a foster home and complimented his memories with fictional elements.

What is memorable about Sunny is the warmth of the art, crafted by soft pen lines that sometimes appear like pencil and aided by atmospheric splashes of watercolors that add depth and shading. Together with the use of homely textures for some of the children’s hair and backgrounds, Matsumoto’s art reminds me of the children’s books I read as a child in Germany, such as the works of well-known author and illustrator Cornelia Funke. Compared with the hectic, angular style of Tekkonkinkreet and the neurotic lines of Gogo Monster, the art of Sunny radiates calm and invites the reader to linger a bit longer with the images. This is also supported by the page compositions which feature wide establishing shots and have a soothing beat with some of the pages punctuated by round panels.

Sunny feels like Matsumoto’s most personal work and depiction of childhood yet. By telling a story about characters for whom their parents are unable to care, who are wounded, it adds urgency to the question of how to preserve a sense of childlike wonder despite difficult circumstances. As Matsumoto’s work makes clear, this is a question worth answering many times over. Reading his books is like listening to a jazz pianist improvising on familiar melodies. Beneath it all lies a silent message of hope: there’s always space to dream.

External sources:

Source 1: https://yokai.com/itachi/

Source 2: Ishii, Anne (August 15, 2013): Bringing Up Sunny: A champion for the bildungsroman publishes his first confessional novel based on his childhood https://www.guernicamag.com/bringing-up-sunny/

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply