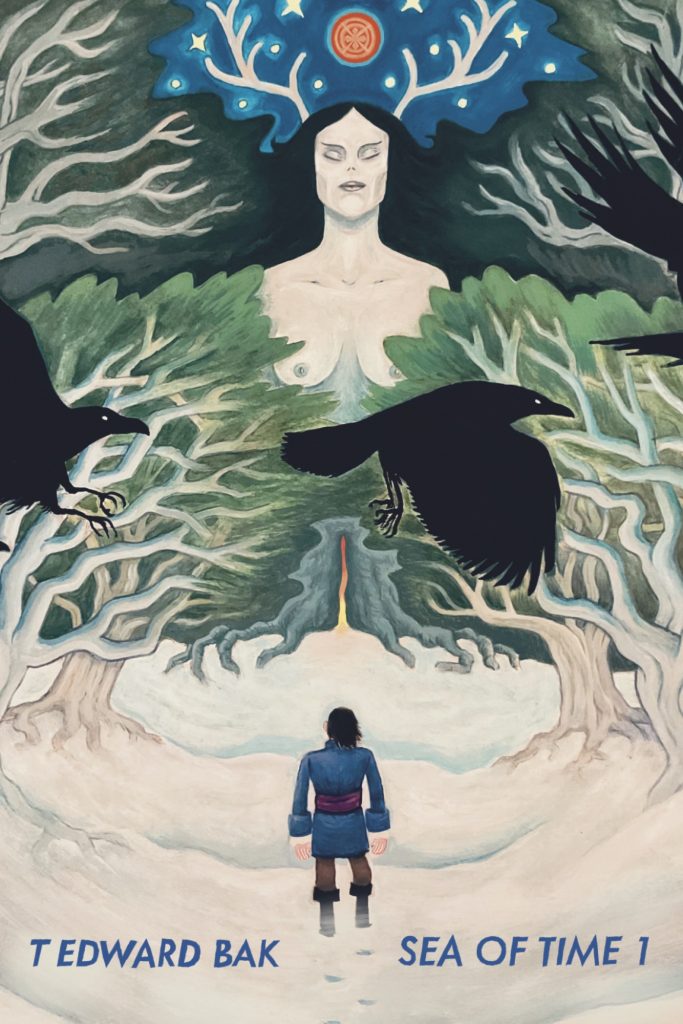

There is a pleasure in being lost, in taking in your surroundings and accepting strange worlds as they are. T Edward Bak, the creator behind Island of Memory and Not a Place To Visit (both from Floating World Comics), has just released Sea of Time, a new multi-volume that weaves together myth, ecological disaster, and natural history.

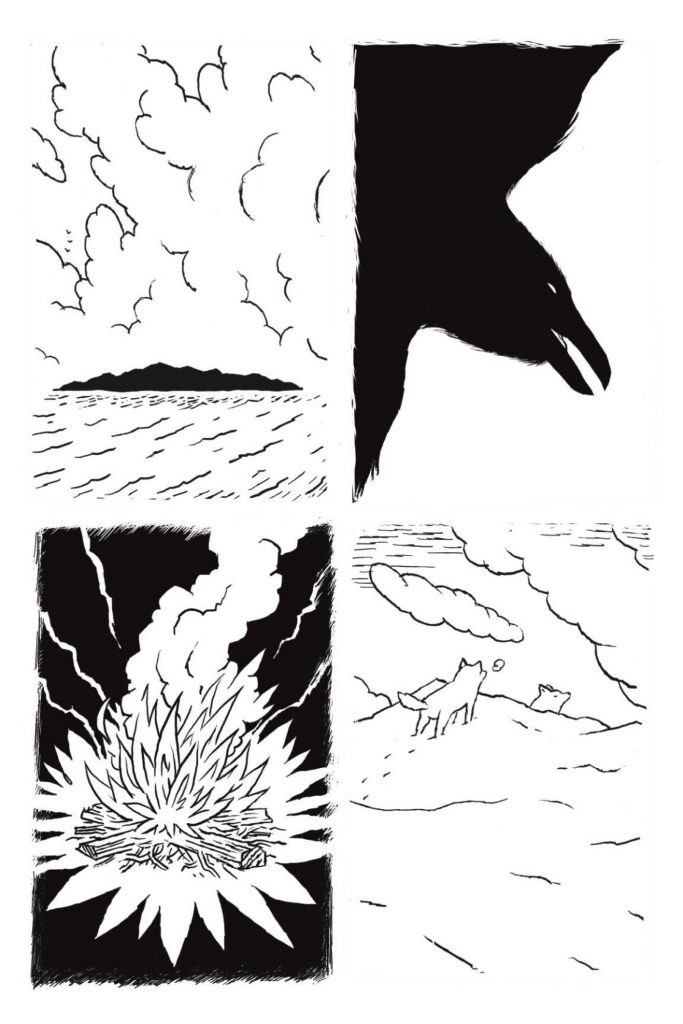

The book begins with a four-panel preamble that sets a questioning tone; who belongs where in the natural order of things? We see wolves covering sailors with blankets, giant hands reaching for spotted mushrooms, indigenous people and a Blue Jay watching a tall ship coming towards them, and a sea full of kayaks, sea lions, and salmon all paddling in the same direction. Turn the page, and you realize that the story hasn’t even begun, that this was simply the page before the title page.

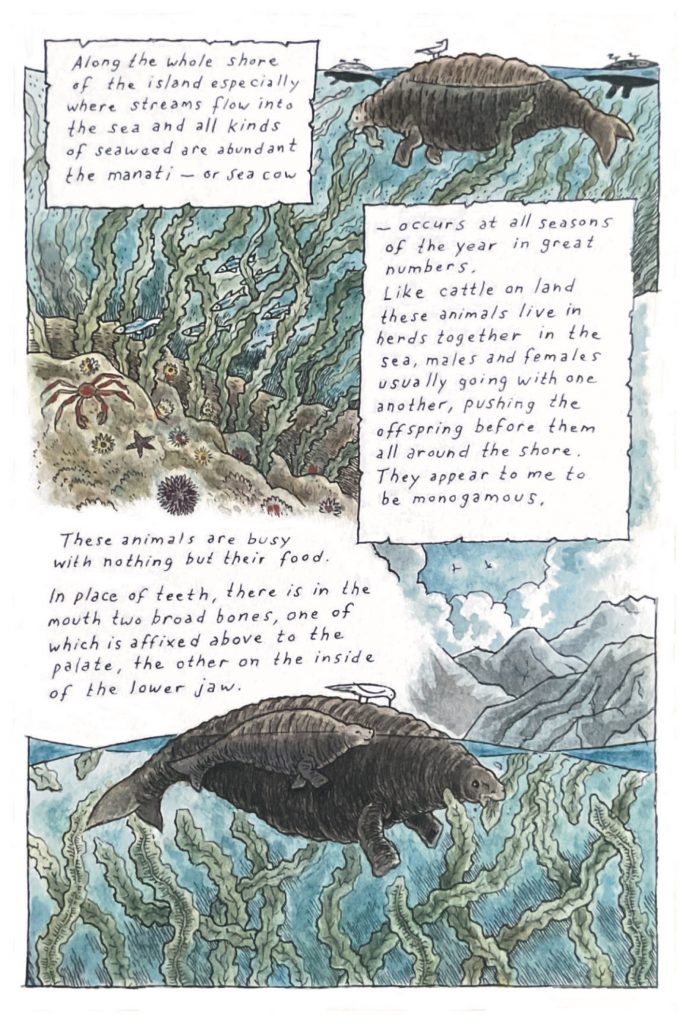

Bak likes to keep his readers off-kilter, constantly questioning where they are in time, place, and narrative. The start of the book has a clear scene; a sleigh of travelers finds a man in the snow, his appearance bringing questions from the travelers and the reappearance of the Stellar Jay from the four-panel preamble. Then one of the travelers sees a mysterious set of antlers in the distance and wanders into the unknown. We also go into the unknown, but it’s a different place than where the antler-enamored man is headed. Instead, we find ourselves amongst planets, blackbirds, fire, and wolves, rapidly moving through a mysterious set of scenes before finally arriving in what appears to be the present, back with the man who followed the antlers and is now evidently participating in a spiritual psychedelic journey. The moment we find ourselves with a familiar character, the sands shift again, and we’re in the pages of a naturalist’s notebook.

I would have been happy to stay here forever; the full-color drawings are stunning, filled with details and observations of the inhabitants of the ocean and its rocky outcroppings. Beautifully illustrated, this part of the story drew me in completely, not just because it has the most conventional story arc. The way Bak uses sympathetic line work and nautical know-how to explain the contrasting relationship behaviors of sea lions, manatees, and otters is an act of brilliant foreshadowing, casting a light on later, less-congruent segments. For a moment, we see a man on a cliff writing, and the story-within-a-story device becomes clear. We’re watching the watcher, and we see his obsessions.

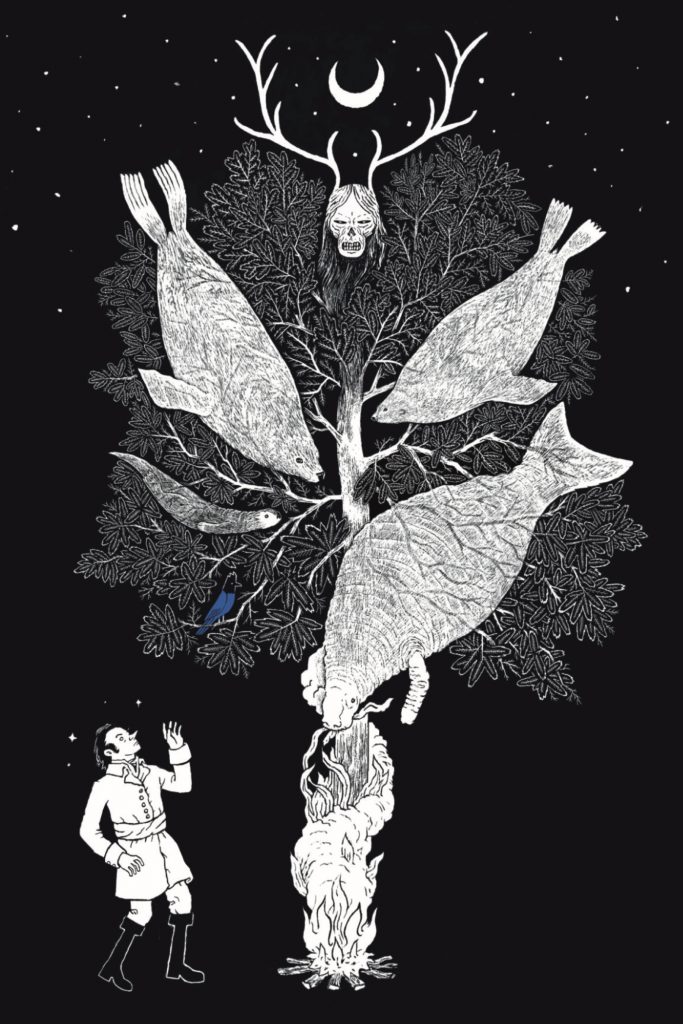

Though the drawings in the notebook section of Sea of Time border on the ethereal, the other sections vary between simplistically symbolic sketches, a solid comic book style, and an almost jarring naivety. Each area of storytelling has its own visual flavor, and Bak has used his immense skill to give you as many clues as he can about when and where you are. The psychedelic plotlines are drawn with weird perspectives and, in places, an artificial flattening of masked men and their symbols. The women in the Saint Petersburg storyline are nearly grotesque, their dialog offputting in precisely the way it’s meant to be. Besides the naturalist’s notebook, the other place where Bak flexes his drawing muscles are in the full-page drawings that combine the creatures of the sea with the symbols from the psychedelic plotlines. Here manatees swim down burning trees, elk and wolves stare at a sky made of lightning, and sea lions are set amongst the stars. Each time Bak takes over a page, you’ll find a trove of mystical beauty and, of course, more camouflaged plot.

The storytelling devices in Sea of Time remind me of The Finder Library, Carla Speed McNeil’s science fiction anthology. McNeil is a master world builder, and The Finder Library is an opus of how different cultures interact in the face of multiple conflicts. It’s epic and not just in its size (I own both anthologies, and they’re over 500 pages each); it’s an incredibly complex and layered set of stories that build on each other while ripping through different plotlines, characters, and worlds. I discovered The Finder Library as an anthology, with all the individual comics compiled into two satisfyingly large volumes. It was challenging to get into, but the world-building was so extraordinary that I stuck with the confusion, secure in my faith that eventually, all of my questions would be answered (in truth, only most of them were, but it remains one of my favorite comics of all time). As I’ve read and reread Sea of Time, I’ve wondered if I would have enjoyed The Finder Library as much if I hadn’t been able to binge it. The shifts in the story, location, and character in Sea of Time left me disoriented; Though every time I felt lost, Bak skillfully brought me back by including dialog that reminds the reader that we’re all lost, and that’s probably ok. In other places, he’ll pivot to a psychedelic ritual to remind us to be seekers or include a scene designed to ground us back in the story, back in a real place and time.

As the naturalist, whose name we learn is Georg, says at one point, “it is enough to observe the mysteries of life.” In this way, Bak reminds us that it’s ok to be overwhelmed; the world is overwhelming. Enjoy these moments for the beautiful things they are. And I do, but it’s hard to stop myself from trying to pull all of these moments together, to try and piece together every scrap of information Bak gives us into one story set within one slim book.

When we leave the naturalist’s diary, we find ourselves rushing between a child in a study with Georg, a party in Saint Petersburg with gossiping women, and a folktale told in an unknown voice. Jumbled together, you find yourself identifying more with Georg, a stranger in an arctic wilderness meeting men with strange eyes and seeing the natural world in a less linear way. Georg’s world is confusing, but he exists as a role model for the reader; though a stranger in strange lands, George always appears to know who he is and what he is doing. I take solace in his confidence and that this is only the first book.

Leave a Reply