It is, perhaps, the inevitable fate of a revolution, after its completion (or failure), to be rendered obvious, subsumed by the stasis of historical memory. In such a case, not much remains of the moment of impact once its revolutionary edges are implemented, and subsequently obviated, by their former loci; not much remains but dust and echo.

Consider Winsor McCay: one of the major progenitors of the comic form (and consequently one of its foremost formalists) as we know it, whose craft, though crude compared to the works whose infrastructure he helped build, still stands up rather beautifully more than a century hence. Yet few people, really, seek out Little Nemo in Slumberland (let alone Little Sammy Sneeze or Dream of the Rarebit Fiend) because they just feel like reading some comics; McCay has long been sequestered into the realm of the archival and ancient, not searched for but only researched, not engaged with in-depth but only echoed.

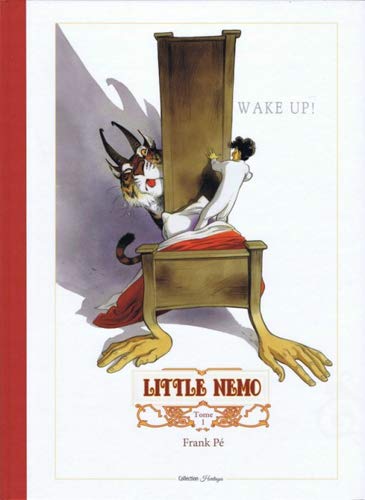

It’s for this reason that I find Little Nemo an interesting project to revive. Frank Pé isn’t by any means the first cartoonist to attempt this sort of revival, only (as far as I can tell) the most recent, but the choice strikes me as potent because of how sporadically it occurs; Winsor McCay’s work has entirely slipped into the public domain, yet it doesn’t get as much engagement as other properties, perhaps because its early-comics crudeness makes it a tougher sell. Whatever the reason (or reasons) may be, Little Nemo, as a property, has reached a grim but fitting end: it is, at best, dormant with no real chance of properly waking up again. It makes any revival an event, simply because so few people bother—which makes it, of course, a perfect vessel for a passion project.

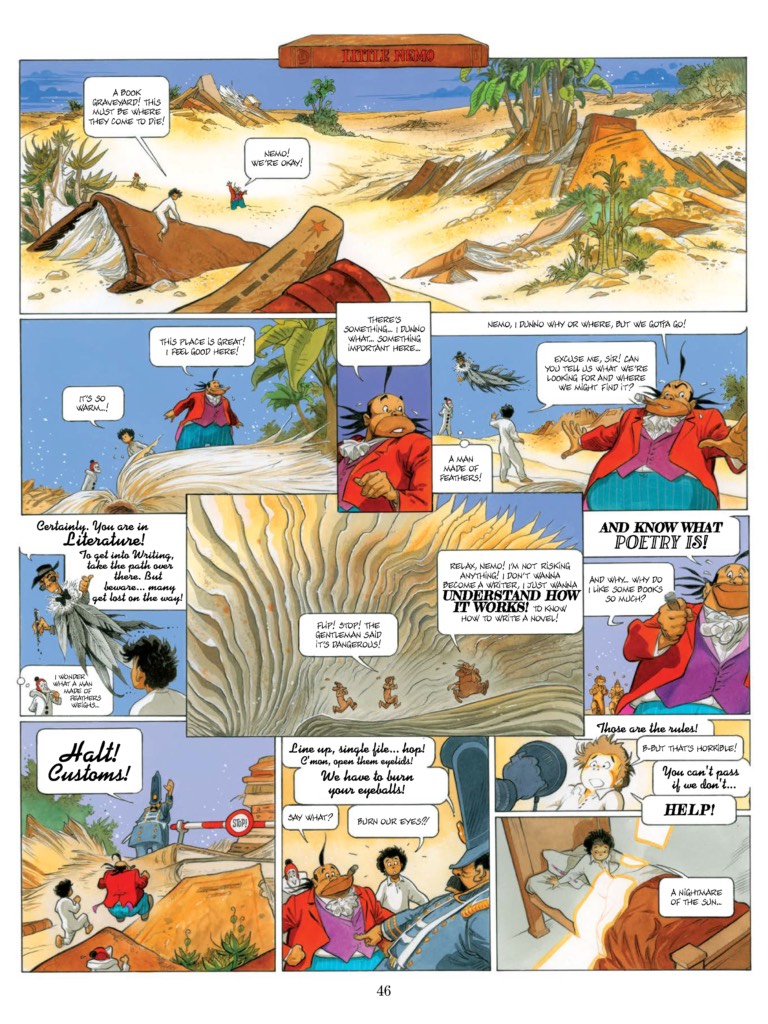

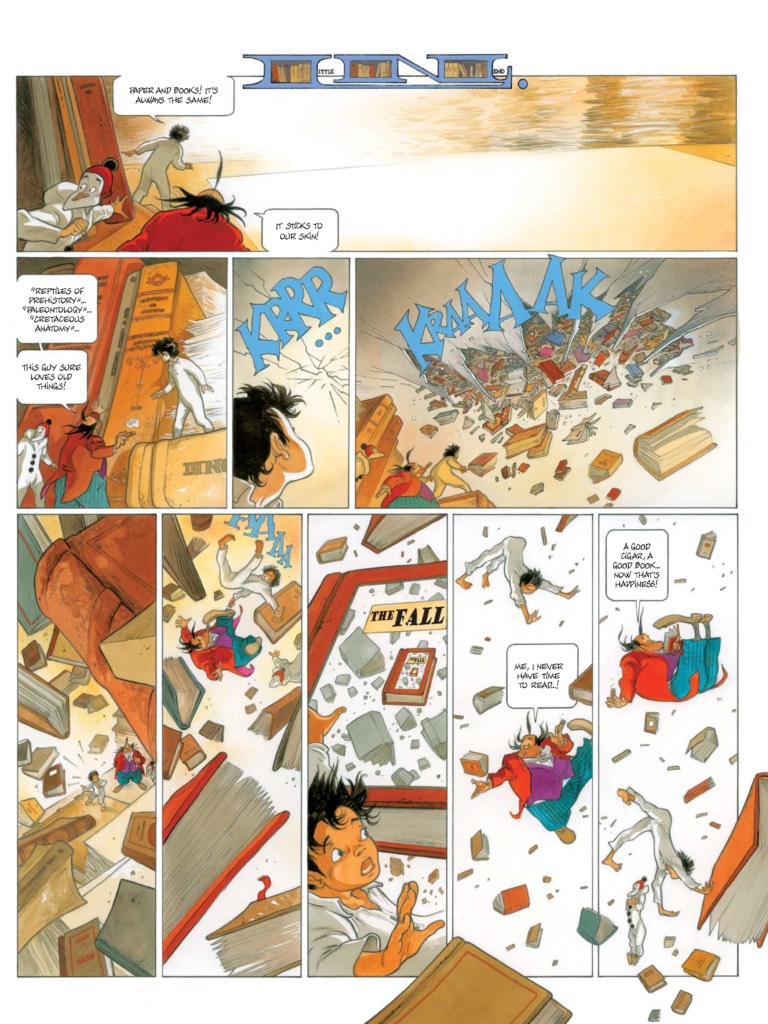

And there is, indeed, a burning passion at the heart of this book. I wasn’t familiar with Pé’s work beforehand, but on the craft level its appeal is instant: his art is lively and smooth, with the same buoyancy in layouts that defined McCay at his best; his pages defy the gravitational physics of the traditional page, swinging up and down and left and right, however the mood strikes him. Pé chooses to tone down the fin de siècle-art nouveau ornamentation that informed McCay’s grasp of architecture and environment, instead opting for an aesthetic closer to the Belgian cartoonist’s home magazine Spirou and its associated stylistic school, characterized by its balance between cartoonish kinesis in character and realism and environment. This is perhaps the key point in which the revival diverges from its source: it strips the comic of its chronological anchor, giving it a timeless feel, its historical edges filed off, more aligned with the book’s self-proclaimed mission statement of modernizing McCay’s opus.

Another attempt at modernizing by diverging from McCay’s source is made in a curatorial decision, in hindsight rather than in the initial conception: in his afterword, comics academic Dr. Stanford W. Carpenter notes that, in the original French, Pé made the decision to include McCay’s character Impie—such a grotesquely racist African caricature, the likes of which have not been seen in American comics since the 1950s and in French comics since… well, since last week, probably—but points out that it was not out of any racist malevolence but simply as an ignorant wish to reflect McCay’s world in McCay’s own way, and that, when he was made aware of it, he made the decision to remove Impie from the American edition of the book, understanding that there is a real-life impact to be considered and taken into account. It’s a noble decision, and it deserves to be treated as such, especially given its broader context—Franco-Belgian comics are so notorious for their defense of that exact same breed of racial caricature under the flimsy pretext of ersatz-Enlightenmentarian worship of “freedom of speech” (The Elephant Graveyard, the second album in Yves Chaland’s The Adventures of Freddy Lombard, came out in 1984, and yet one could easily place it beside 1931’s Tintin in the Congo so as to say “nothing has changed”) that the decision denotes an owning-up and attempt on Pé’s part to break from both his source material and his surroundings as a creator.

Unfortunately, these divergences don’t particularly manage to hide the truth, which is that Pé’s revival, like others before it, owes so much to McCay’s aesthetic and structuring as to be caged by them, not leaving much room for something new. In other cases this would not be a problem—large swaths of superhero comics offer, and indeed depend on, not much beyond the echoing of a previous, more successful text, so this is hardly anything new—but that proclamation of modernization fails to live up to its own expectations. If you were to judge this release on its own, unaware of its 20th century inspiration, you would not really be able to find anything modern about it, nor anything novel. As you read on, you understand that it isn’t that the appeal is instant—it’s that it’s too instant, too easy. This is reflected in the author’s own introduction, where he says “I wanted to test some themes of the modern world to bring it closer to us: cigarettes, virtual images, neo-dinosaurs… What a pleasure it was to give a tyrannosaurus tattoos and piercings!“: a grocery list of things that exist in that “modern world” that Pé purports to comment on (an observant reader may note that many of these objects were, in fact, extant even during Winsor McCay’s lifetime), but don’t particularly say anything of note about it. In Pé’s world, time boils down to an aesthetic to be swapped out every few decades, washing over one without making even a dent.

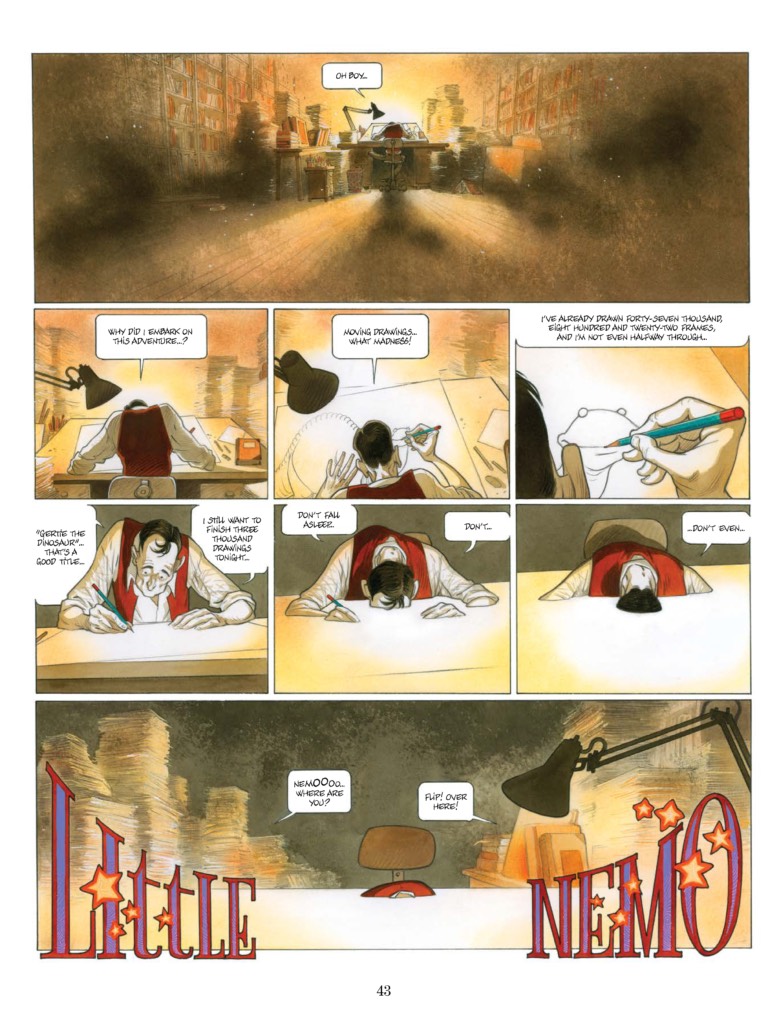

This refusal of properly meaningful engagement appears to be a rather persistent theme in this book, particularly evident in one of its more perplexing decisions: in some of the pages Pé chooses to pivot to Winsor McCay himself as a character, but instead of opting for direct biographical (or even pseudo-biographical) moments, the author props up parallels between Little Nemo and his creator, depicting McCay in his studio or in his home as his reality is ruled by his dreams—and consequently, for a professional dreamer like the cartoonist, by his work.

There could have been a tragic undertone to these pages: look at this brilliant cartoonist, whose imagination became his burden because he never stopped working on it; he yearned for the simplicity of childlike wonder but was defeated by the waking adult world. As Pé himself writes in that same introduction, “[i]t is not known if Winsor McCay had an ultimate dream at the time of his death on July 26, 1934. We’ll never know. But we can certainly imagine it. With conviction and absolute freedom”—and imagine he does, with too much freedom; there doesn’t appear to be any real interest in McCay as a person, only as a character, as if the author clandestinely admits that it is simply easier to project on his subjects, to make up a version of your artistic heroes, than it is to consider their real-life namesakes. McCay’s appearances, as a result, feel like a half-baked shorthand without much in the way of care or impact, leaving Pé with a shallow, unearned half-message that feels weightless more than anything else.

Is it the inevitable fate of a revolution, after its completion (or failure), to be rendered obvious, subsumed by the stasis of historical memory? Can nothing new be said or built on that basis? Must the memory of innovation be reduced to dust and echo? Judging by Frank Pé’s Little Nemo, where change only exists either as an aesthetic or as an enforcement of the original state, the answer appears to be an all-too-resounding yes. The book is not without its merits—even outside of my general support of increased self-indulgence for its own sake in art, there’s a joy in the art that cannot be overstated—but those merits are almost entirely shackled to a veneration of source-text that precludes actual discourse. It is a product of absolute saccharine comfort that expects a total agreement from its readers—not only on the untouchable stature of the work discussed, but on the mode of consequent engagement: sweepingly superficial, enamored of its totality in (almost) the most conservative way possible. With his Little Nemo, Frank Pé dreams himself into being—but at the price of actively refusing to wake up.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply