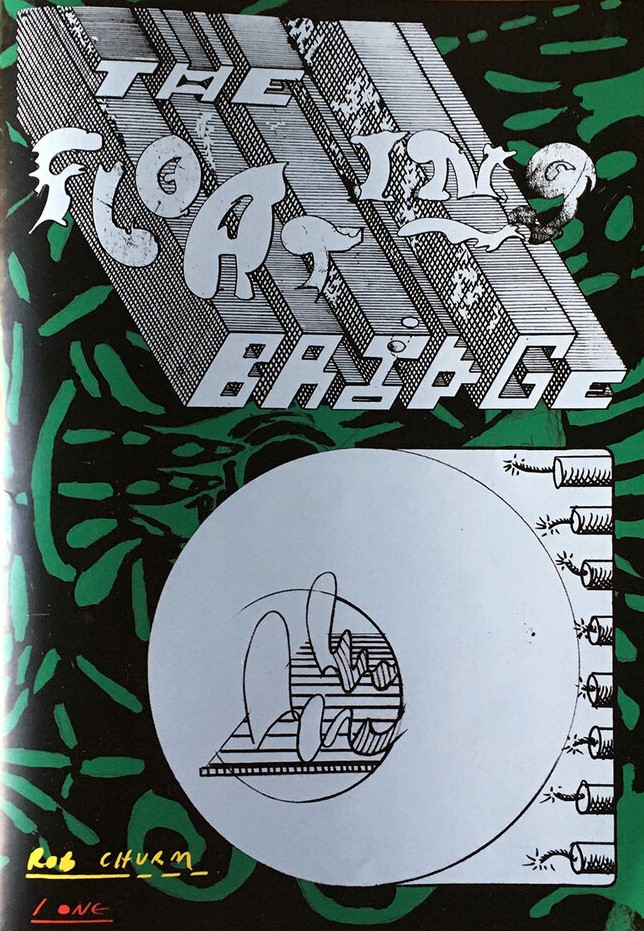

Comics are so well-suited to narrative and character that it’s easy to forget that this is not, intrinsically, a narrative or representational art. Though plot and character arcs can be nice, a comic at its core is a sequence of marks on a page. The Scottish artists Rob Churm and Malcy Duff foreground this understanding of comics as being first about the drawing and the interaction of images, and only secondarily about the ways in which those drawings can generate ideas or stories. Their mind-expanding 60-page split magazine The Floating Bridge, the first issue of a projected series, ably demonstrates just how much can be done within a comic from this starting point.

Churm and Duff are in many respects quite different artists. They each approach ideas about abstraction, figuration, and narrative from unique angles of their own, and, on the face of it, they wind up far apart visually and conceptually. This aesthetic gulf, as much as the many resonances between them, is what makes The Floating Bridge so exciting. Openness to confusion and ambiguity unites their disparate approaches, producing some of the finest abstract or near-abstract comics the medium has seen. These comics baffle the senses, teasing the reader with half-submerged hints of form and meaning that twist away from view before they can be fully grasped.

Neither Duff nor Churm prioritizes narrative progression. There is definite sequential movement in their work, but the sequence between panels is better thought of in terms of rhythm, patterns, and symmetry/asymmetry. Being musicians as well as artists, they’ve borrowed 7” single marketing terminology to dub this magazine a “double A-side” split, prodding the reader to think about the visuals musically. Though the resulting sides look and feel very different, they both explore the ways in which panels and pages can form beats and visual rhymes. These ambiguous connections, not narrative, drive the eye from panel to panel.

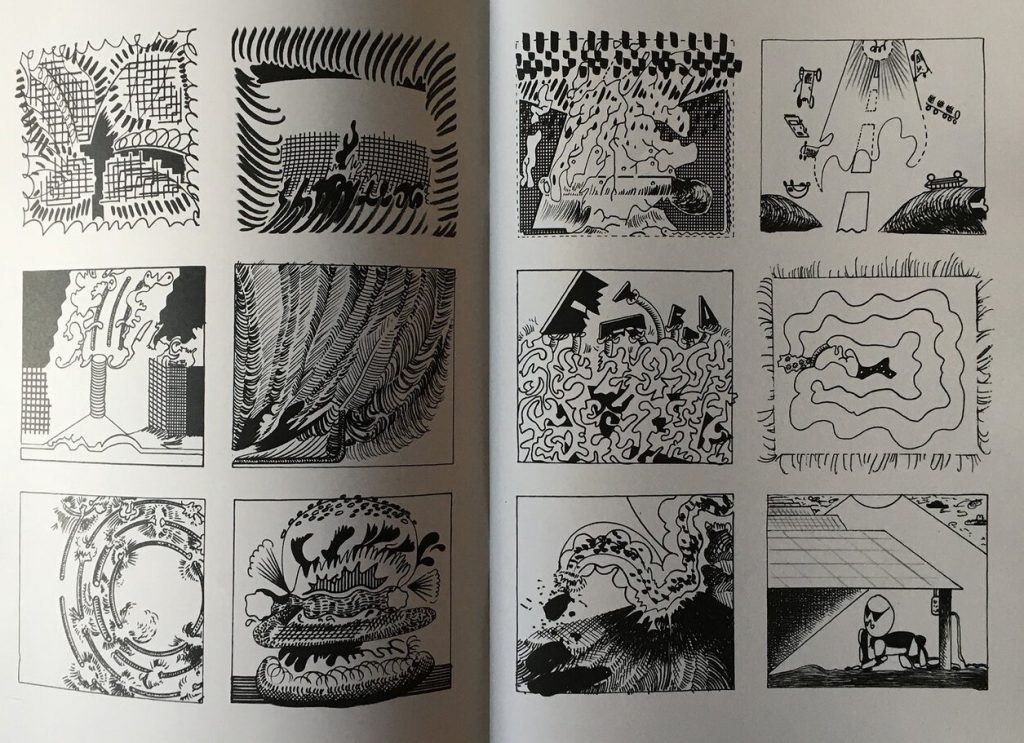

Churm’s half of the book frustrates and questions the desire for figuration and narrative at every turn. Working for the most part within a six-panel grid, Churm unleashes a torrent of vivid but deliberately imprecise imagery. His drawings exist in an uncanny valley, suggesting but never fully embodying recognizable forms and shapes. Many of his images can just as easily be read as dense abstract patterns with no tangible reference point. On the first page alone, what seem at first to be stray lines cohere into an arm pointing off-panel, and then a corpse being dissected by birds, but the progression gets hazier from there. By the last panel on the page, the vague shapes of the birds are just barely recognizable, subsumed into a complex network of squiggles, cones, and looping geometric structures. Any understanding of the events becomes poetic rather than concrete.

The result is akin to the graphic notation of some 20th Century avant-garde composers who eschewed the fixity of most composed music for image-based scores with the interpretation left open for a performer. The reader of these comics “plays” the score laid out by Churm’s drawings in a similar fashion. What the comic means and communicates can’t be the same for any two readers, any more than two performances of Cornelius Cardew’s graphic masterpiece Treatise would ever sound the same.

Churm’s pages leap back and forth between virtuoso pure drawing and more easily parsed figurative work, with hints of cartoon iconography showing up as well. There’s tremendous variety to the mark-making and the techniques he’s using, which results in pages that radiate energy and intensity even when (or especially when) it’s not clear what, if anything, is actually happening. Thick marker blocks sit side by side with more precisely inked lines, feathery un-inked pencils, swooping brushstrokes, and countless other subtle gradations of implement and technique.

The complexity and ambiguity of the drawing means it’s endlessly rewarding to read and re-read this. Churm offers up shards of recognizable action to hold onto: a man with a sword atop a pile of corpses, a sparking dynamite fuse, an exploded cubist view of a scientist peering into a microscope, a fish being speared from the sea. In place of a clear overarching plot, Churm creates a sense that forces of change and evolution are at work. Violence and bodily mutilation are common motifs, as are images that evoke creation and the natural world. The more abstract passages frequently suggest churning seas, howling winds, a dandelion spewing pollen, or flurries of war and dismemberment.

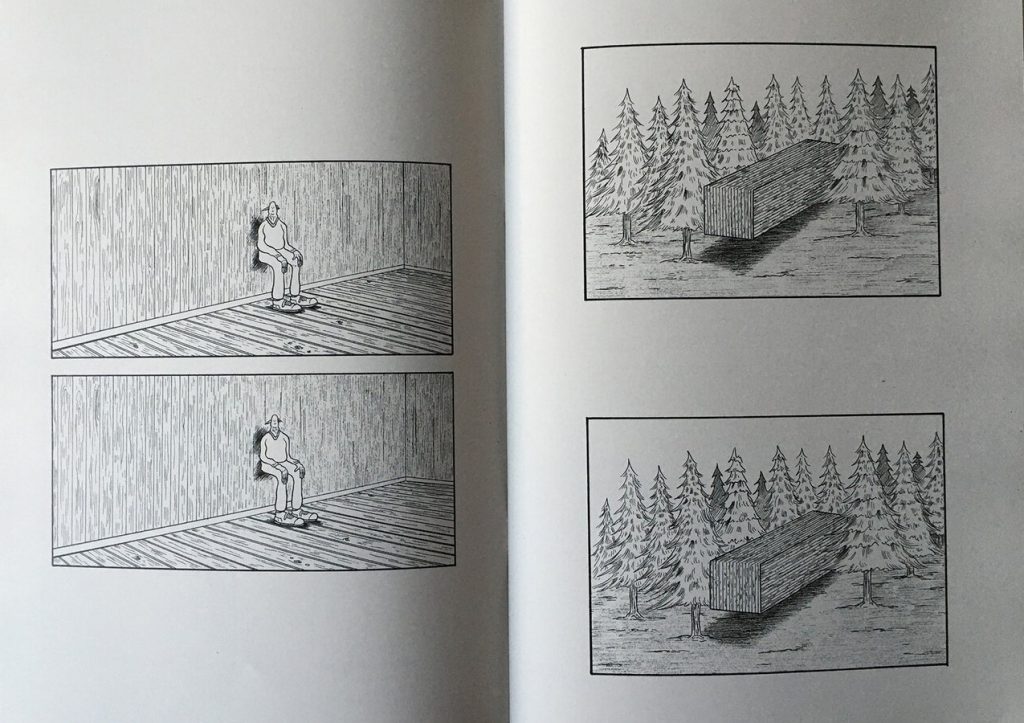

Duff, in contrast, works solidly with figuration and representation. His drawings veer into abstraction in subtler ways, mainly in the way he deforms and toys with the human figure, but his work is no less discombobulating than Churm’s. Even with a bigger back catalog in comics to draw on than Churm (whose previous publications, other than The Exhaustion Hook, have mostly been illustration and poster design), Duff’s work doesn’t yield easily to interpretation. Duff’s comics encourage hyper-awareness of basic formal elements. The changes between images are often tiny, which places greater emphasis on panel placement, the white space of the gutters, and small nudges to the angle of view. Repetition and subtle shifts in perception are the signature tools in Duff’s repertoire.

This comic consists of a few recurring images which are repeated, shuffled, and slightly tweaked over the course of the story. Duff has at times portrayed the act of drawing as a theatrical performance or a magic show, depicting transformations and optical illusions playing out upon literal or metaphorical stages. Even in a piece like this, without any explicit stage or curtain to raise, the stiff posing and distanced framing with which Duff places objects and figures are deliberately stagey. Duff always evinces an awareness of the audience, and, consequently, can play games with that audience, like repeatedly altering the angle of an otherwise straightforward view of a bench to raise basic questions about the contents of the scene. How many benches even are there? And who’s looking at them?

Though the formalist framing is tricky, the images are relatively simple. A large wooden rectangle floats in a glade of trees. A man with an eel-shaped head sits uncomfortably, straight-backed against a wall. A bench sits in a field, mostly holding its form but occasionally morphing to reveal that it was once a person. Duff cycles through these images stoically, often repeating the same panel several times in a row with minute variations. The figures, when they speak, have only blank word balloons floating above them, waiting to be filled with any thoughts the reader wishes to project onto them.

Duff’s drawing is precise and very beautiful. There are a lot of different wood textures in this comic, and he renders them all impeccably, limning every knot and line. The solidity and detail in the settings of Duff’s comics enhance the oddity. Everything is rendered with such concreteness and weight that when he draws something that doesn’t obey those same physical rules, it’s even more destabilizing than it would otherwise have been. His figures especially tear at the boundaries of conventional representation. The main character has a fairly ordinary torso, but from the neck up everything is off-kilter. His neck curves out oddly and is marked by a web of crisscrossing lines that don’t signify any known anatomy, while the rest of his head is snakelike with goofy cartoon squiggles of hair protruding nonsensically from the sides. The second figure to appear is even less stable – it’s like an optical illusion or a Rorschach blot, a combination of a chair and a person that suggests different shapes from different angles or to different viewers.That kind of ambiguity is integral to both halves of The Floating Bridge. Duff’s images are largely understandable on their own terms, but prompt deeper investigation through the rhythms of panel placement and composition. Churm instead plays in the space between form and abstraction, never fully committing to either but letting the two impulses weave together until they’re inseparable. Both of these comics are excellent and thought-provoking on their own, but they also complement and enrich one another, their different approaches working well in counterpoint. Together, they present an exciting composite vision for comics’ outer bounds.

Leave a Reply