In Fine: A Comic About Gender, Rhea Ewing combines their story of questioning their gender with fifty-six interviews they conducted with people over the course of a decade about their experiences and ideas. The combination creates a work of graphic nonfiction that provides a solid overview for anyone seeking to explore and understand gender and sexuality in the twenty-first century. The strength of the book, in fact, is the diversity of voices Ewing brings to the conversation. The inclusion of Ewing’s own story shows how and why people ask the questions they do, while the subjects of their interviews reveal a much broader range of experiences than Ewing could ever do through only their story.

Ewing begins the book with the basic questions of masculinity and femininity in our culture, which, quite naturally, leads to questions of gender roles. Ignacio, for example, makes the point that most people in society don’t like it when others blur the lines of masculinity. Of course, it’s much more acceptable for a person who presents as a female to be more masculine than it is the other way, given the strict interpretation of masculine roles in our society. I even find myself wanting to put words like masculine in quotes when discussing this work, as language around all of this conversation is ever-changing and slippery, at best.

Ewing reinforces the idea of a broad spectrum of gender through their artistic choices, as well. The people they interview represent a wide variety of presentations, and Ewing clearly communicates that diversity. Some interviewees purposefully present as more masculine, as does Ewing at times in the work, and their art highlights that aspect of their personality and presentation at those moments. The same is true for more feminine presentations, even for Ewing when they’re struggling with how they feel about their appearance. Ewing works to portray those who purposefully present as gender non-binary–some by embracing both traditionally masculine and feminine aspects, some by trying to negate those aspects–as clearly and accurately as possible by drawing them as close to how they present as Ewing can.

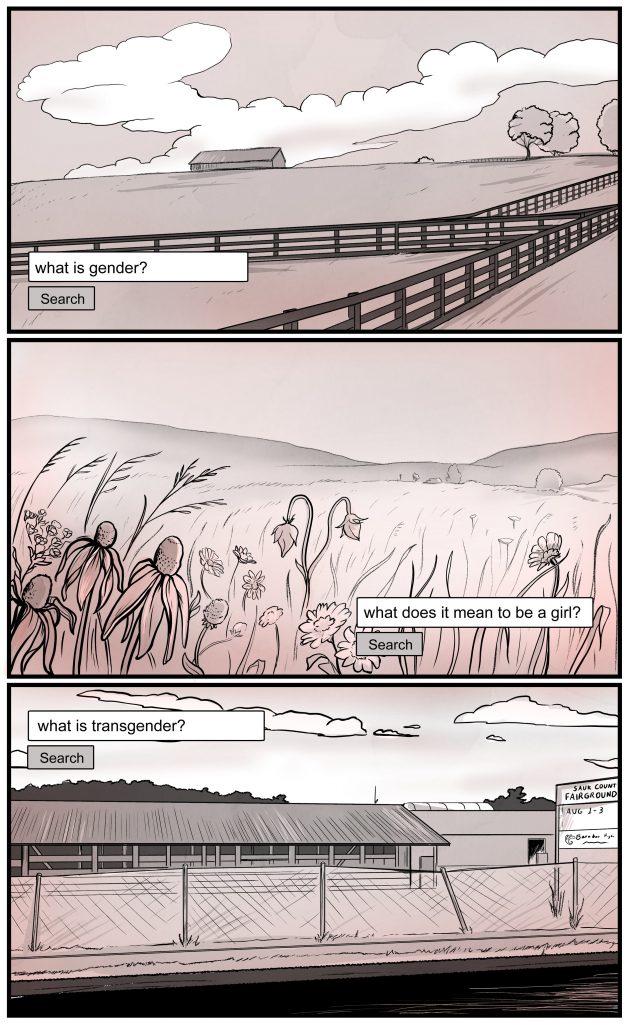

Ewing uses the background surroundings and clothing to reinforce that idea. At times, they’ll move characters from one location–the coffee shop where they’re having the interview, for example–to a radically different one–a wide-open meadow, say–to reflect when an interviewee talks about feeling free. Ewing might also change an interview subject’s attire when they talk about how they’ve changed their presentation over the years or even how they perceive themselves on a moment-to-moment basis. Thus, a non-binary character might move from traditional masculine clothing to traditional female clothing and back from one panel to the next, as Ewing uses their art to reflect the changing self-perception of the interviewees.

Not surprisingly, Ewing deals with language several times throughout their work. The most obvious is pronouns, which leads Ewing to interrupt one of their own interviews (with Enne). Ewing expresses their frustration with wanting to use gender-neutral pronouns, as it doesn’t bother them that much when people use the wrong pronoun, but it makes them feel “extra warm and fuzzy” when people do use the correct pronoun. Ewing feels guilty for wanting to feel that way all that time, but, as Enne says, “…Maybe you should” make a big deal out of it (154).

However, it’s not just pronouns that are the linguistic problem. Contemporary Americans interchange sex and gender on a regular basis, usually incorrectly. However, even some of Ewing’s interviewees want to see more flexibility with those terms, believing that complicating those terms would provide more freedom. As Mo says, “I feel like it’s hard to describe them in a way that isn’t shoehorning someone into an uncomfortable space, probably? The difference between sex and gender is something I feel ill-equipped to discuss without feeling like I’m screwing someone over” (133).

Ewing’s work also turns the gaze outward, as well as inward, by talking about issues in healthcare. Even if somebody is comfortable with themselves, there are societal systems in place that limit the freedom they have to be that somebody. The interviewees describe the obstacles that prevent them from getting the hormones they need or having easy access to a therapist, not to mention simply finding a doctor who understands the particular concerns they have as patients. They contrast those doctors who understand their full selves and those who seek to cure them, in one form or another, often leading to additional months and years of trauma.

It is in the societal issues section of the work that I wanted more. Ewing talks about homelessness, especially for trans* kids, and the much-publicized bathroom debate, but I wanted more of the interviewees’ experiences and more commentary on what has and hasn’t happened legally and politically. Ewing simply raises the issues, then moves on rather quickly, as they move toward the end of the work. It could simply be that the interviewees didn’t talk about those subjects to the extent that they did others or that Ewing was more interested in ideas they had struggled with to get to where they are. However, the stories that Ewing does include on both of these issues give just a glimpse of the daily struggles that LGBTQ+ people face, so I wanted more.

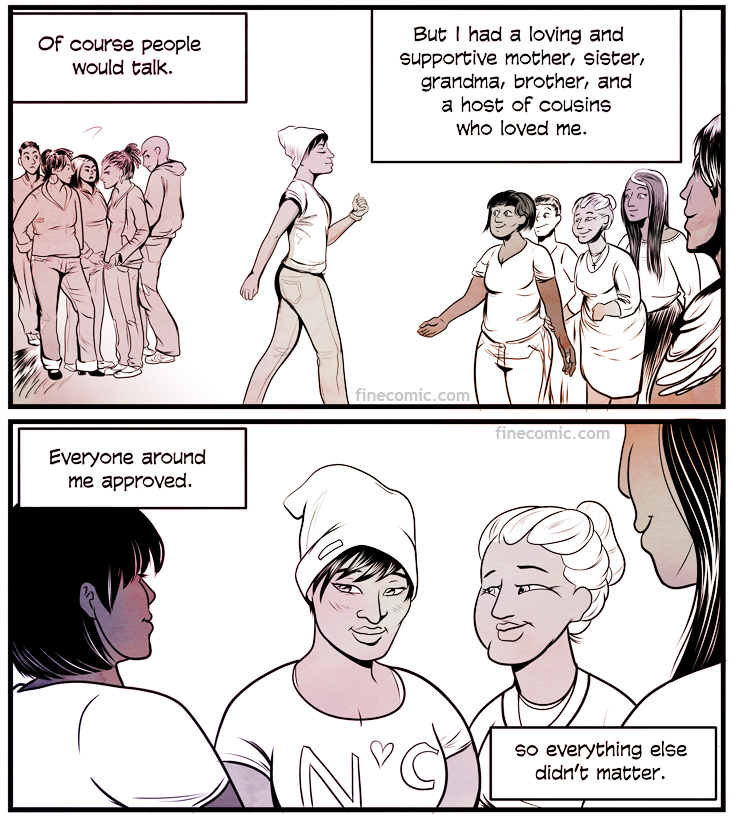

In contrast, Ewing’s exploration of the LGBTQ+ community, in general, worked quite well, as it comes near the end of the book. That section begins sounding very much like it’s a solution to the problems they’ve raised, as Ewing’s interviewees talk about how important the community has been to them, how, in some cases, it saved their lives. However, the stories become more complicated, as several people have felt excluded from that very community. For those outside the community (like this reviewer), it provides a necessary reminder that there is also discrimination and exclusion that occurs within groups, as well as from without. It should also serve as a reminder for those within the LGBTQ+ community that there is still work to be done within the community, as well as without.

Ultimately, Ewing doesn’t end with easy answers, as there just aren’t any. On a personal note, Ewing has found love with their partner Ezra. Ewing not only presents their marriage near the end of the book, but also points out that many of the people at the wedding were people they met through the course of this project. They reflect on how they want to keep listening to others, to help create places and institutions and language wide and broad enough to include everybody. Effectively, Ewing creates their own community to help them as they’ve moved through this part of their understanding of themselves.

There’s also the solution provided by Mara in one of the last interviewees’ comments in the book. Mara says, “Gender is this thing that we all experience in kind of weird ways, and wouldn’t it be cool if we all just talked about gender the way that we talk about falling in love? Everybody falls in love—well, maybe not everybody, but a lot of people—and in a lot of different ways, and it’s kind of weird, and you can have conversations about it. That’s what I want” (281). Mara reframes the conversation with the analogy of falling in love, a mysterious process that so many people experience, but that so many people would struggle to put into words. That struggle doesn’t make the feeling and experience any less true; it just makes it complicated. Like sex and gender. Like masculinity and femininity. Like life.

Even the art is more complicated than it seems, though not noticeably so. Ewing admits in a note that drawing the interviewees who wished to remain anonymous was particularly challenging. Ewing wanted to portray the key aspects of who they are, while also preserving their anonymity. Thus, they tried to accurately reflect how they presented themselves, including the traditional markers of gender and where/how that particular subject was expressing themselves in ways that deviated from the societal expectations, but not give away any key physical representations of who they are. There is even one interview who is listed simply as Very Anonymous and drawn with a paper bag on their head, as if Ewing struggled with how to convey someone who clearly wanted nothing at all known about themselves. Ewing ends the book with a reading list for those who want to delve deeper into the ideas they’ve laid out. As with the rest of the work, it’s not highly academic or technical, as is fitting. They’ve listed more resources on their website, as well. They begin the book with a page of resources for help, and there are more of those on the website, as well. Beginning and ending the book this way reminds readers that real lives are at stake here and that further education is a way to help save those lives. This book is a good place to start that process.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply