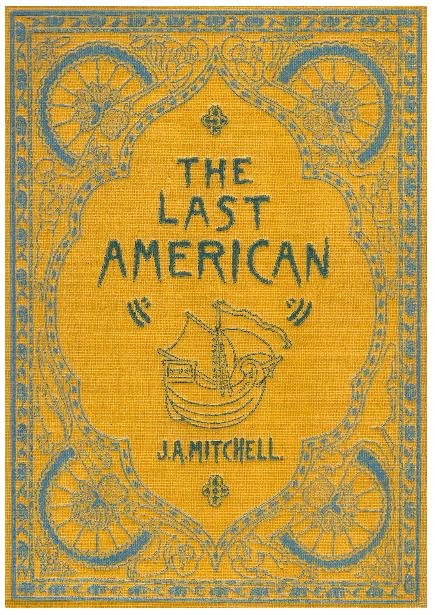

In 1889, John Ames Mitchell (a writer, an artist, an architect, but probably most familiar as one of the founders of Life magazine) published a short illustrated novel called The Last American. Surprisingly enough for the period and person, it is a science fiction story. Taking place in the far future, the 26th century, it chronicles a Persian ship that chances upon an unknown land – that quickly reveals itself to be the lost ‘Mehrika,’ depopulated centuries before due to climate change. The commander of the ship and his crew proceed to explore the desolate land and make many bold explanations of what they see in a combination of a parody of colonial exploration fiction and contemporary satire. Chancing upon the Astor House Hotel, the Persians assume it is a temple meant to house the deity ‘Astor.’

Commenting upon the nature of that lost people, the Persian guide says, “They were a sharp, restless, quick-witted, greedy race, given body and soul to the gathering of riches. Their chiefest passion was to buy and sell.” It’s not a great book, even as it parodies the type of fiction that exoticized others – it very much presents its main cast as familiar caricatures – but it is a fascinating one, especially arriving from such a mainstream source. Already they were imagining a post-American world. Not just a world without America, but a world in which America is barely even a memory. The crew does find the titular Last American; he dies, of course, on the Fourth of July. It is a moment that is both tragic and comedic, appropriate for a text that uses very broad humor to discuss some very big topics.

Fast forward 100 years, a different type of illustrated novel about national death was about to be published. Granted, it has been delayed due to an illness of the artist, running the perfect symmetry by coming out in 1990 instead. It’s also not a “novel,” being a serialized comic-book mini-series. Still, it bore the same name – The Last American. It was published by Epic Comics, a creator-owned division of Marvel Comics that died not long after (more on that soon enough); though they never bothered to collect it. It has been collected twice since then, once by Com.X (ask your grandparents) and, most recently, by Rebellion, home of 2000 AD, for reasons that are perfectly clear.

The series was lettered by Phil Felix. It was drawn by Mick McMahon. It was written by John Wagner and Alan Grant. Alan Grant died recently, which is probably why I’m thinking about The Last American. Though, truth be told, it is never been too far away from my mind ever since I first read it. It is a work about death, after all. Death in micro, death of loved ones, death of the self; and death in macro, the death of millions, the death of nations, the death of ideas, the death of hope. Things fall apart, the center cannot hold. At best, you’ll find some trunkless legs in the desert. A remnant of memory.

When The Last American (the comic book) was being crafted and published, people still thought about the end times in terms of nuclear holocaust. The Cold War was growing colder but most had no way of knowing it, only fearing what would happen when it got red-hot. In 1983, a false alarm in the Soviet early warning system nearly started World War III. The USSR ended up collapsing, ushering in a short age of US global dominance, but the nukes were still there. Other countries have them, others still develop them. I’m more worried about a The Last American (novel) style climate catastrophe, but we can go either way. Maybe both at once. Maybe something else entirely.

The Last American (that’s the comic book again) also came out during a time of creative death. The Grant / Wagner partnership, so fruitful for a decade, was coming to an end. Tensions had ramped up due to a disagreement on Judge Dredd storylines as well as on The Last American itself. Apparently, instead of the usual method of writing together, this series was written by halves – the first two issues by Wagner, the last two issues by Grant. This probably explains the tonal whiplash. Issue two has a dance scene with zombies (or hallucinations of zombies). Issues three and four are a long-form mental breakdown. Which is not to say The Last American doesn’t feel like a whole piece when read, but, once the context is learned, it’s hard not to notice these things

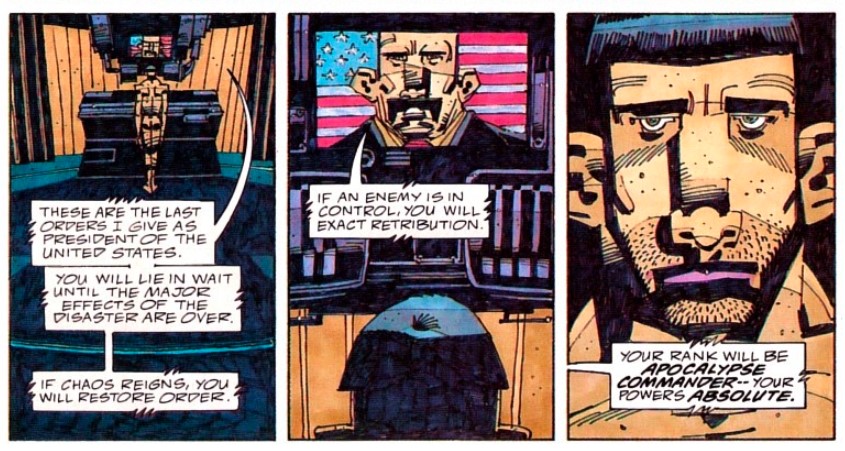

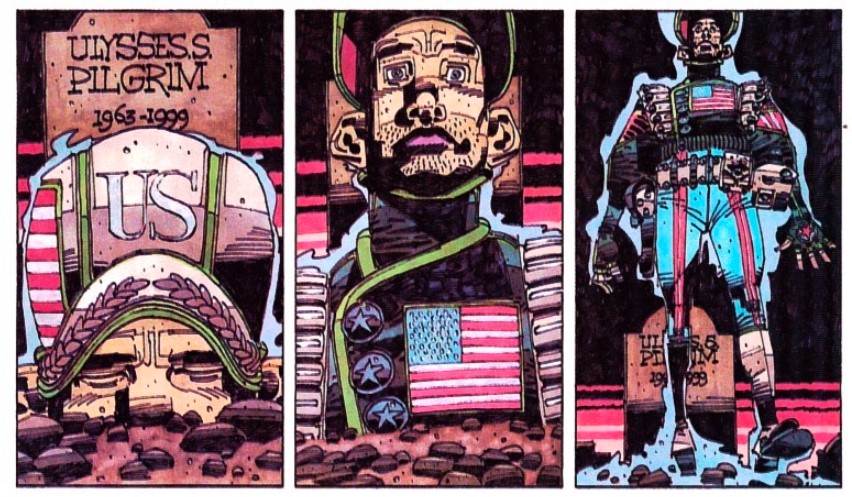

Since I’ve mentioned both Judge Dredd and some story elements, I might as well sum up the plot of The Last American (the monthly pamphlet version): in the far off year of 2019 (we’re already laughing a bit), a man wakes up from suspended animation. His name is Ulysses S. Pilgrim – the writers always loved obvious names – and he is a soldier in the United States Army. Or at least he was. As the nukes were flying, he was put under in order to wake up when the radiation came down in order to look for survivors (if the US won), or exact vengeance (if the USSR won). With the assistance of three robots, Ulysses sets on an odyssey in search of life.

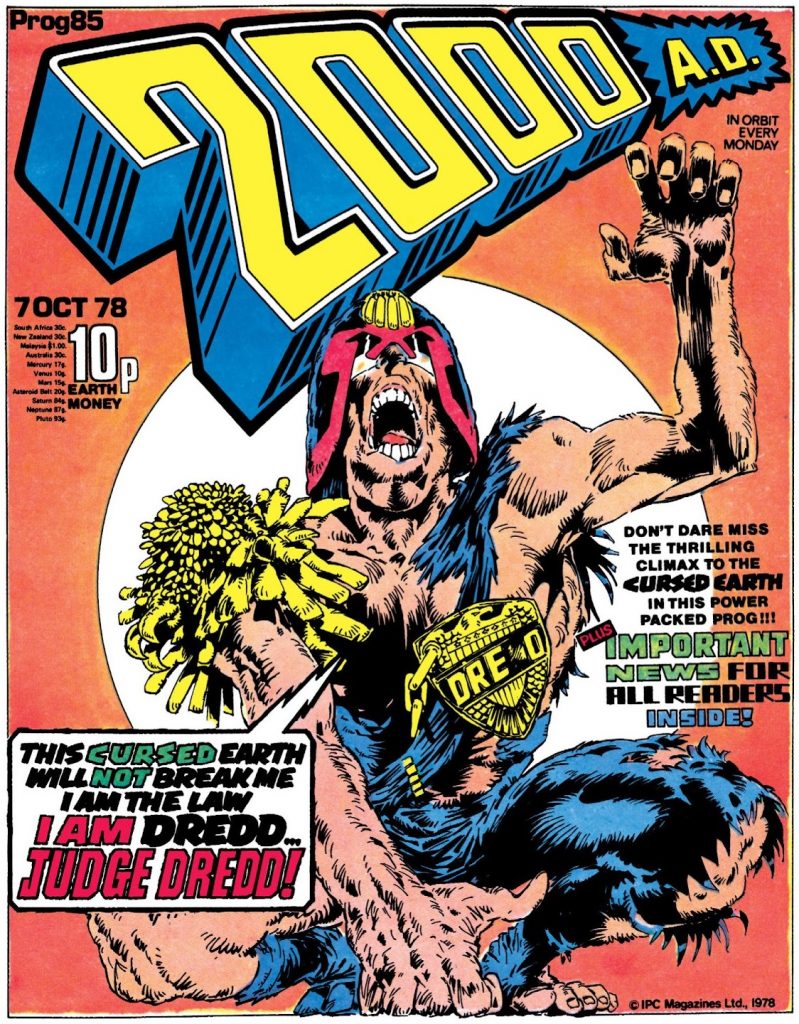

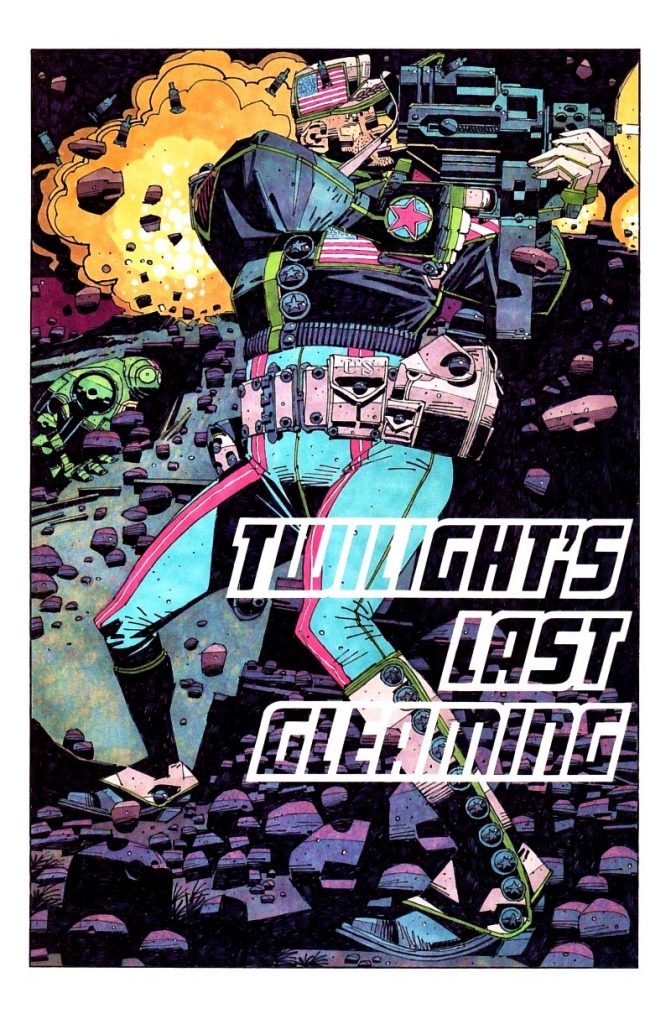

Now, this all sounds very familiar. We have here an American white male with experience in dispensing violence, wielding a big gun, tasked with bringing order to a post-apocalyptic reality. Heck, even the three wisecracking robots appear oddly familiar to anyone who read Judge Dredd: The Cursed Earth. John Wagner, of course, is the co-creator of Judge Dredd. Alan Grant co-wrote with Wagner some of the most famous stories in Judge Dredd’s history. Mick McMahon was the person who drew the first published Judge Dredd story. So why do all these fine British gentlemen (and Phil Felix) have to move to American shores, doing a knock-off version of their most famous work?

The answer is – because it couldn’t be any other way. The Last American appears, on the surface, to be diet Dredd. It is not. It is, instead, Dredd stripped – stripped of all the accouterments of genre fiction, stripped of the protective humor lair, stripped of the commercial need for an appealing hero. The first Judge Dredd script that Wagner wrote, the infamous “Bank Raid,” was rejected by the publisher because it was too dark, too grim. Dredd was wholly unsympathetic. Likewise, the many subsequent rewrites until the finalized, published, version (“Judge Whitey”) which balanced out Dredd’s violence with criminals who ‘had it coming.’ It was, commercially, at least, the smart choice. The one that guaranteed Judge Dredd would keep going on (and on, and on).

The Last American possesses all these familiar ideas, these visual cues, even much of the same bleak humor… but it’s a completely different work. It feels different. Like a familiar jazz musician, a master of his craft for ages, suddenly taking on drone music. You can still tell it’s them, but – at the same time – it’s not them. It’s someone they could’ve been in another life.

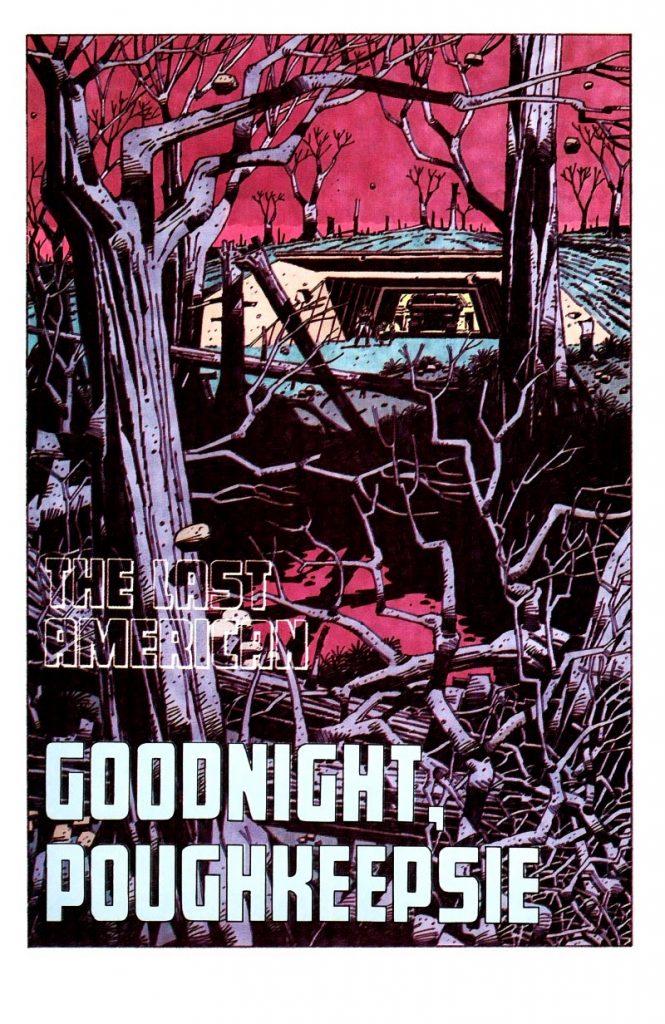

The starting point is McMahon’s artwork. Always an artist prone for cartoonish exaggeration, his big-booted, wild-moving take on Judge Dredd was almost shaggy in its affect, The Last American finds him adopting that style that serves him to this very day. Leaving behind all signs of the respected British artist, the kind that could once grace the pages of The Eagle, in favor of something closer in spirit to alt cartoonists of the 1960s, the characters appear to be spread across the page, sometimes approaching 2D status. Dredd might have an over-the-top chin, but in the case of Ulysses, everything is like that. His face appears downright cubist, his ears like massive sails flapping at the side of his square head.

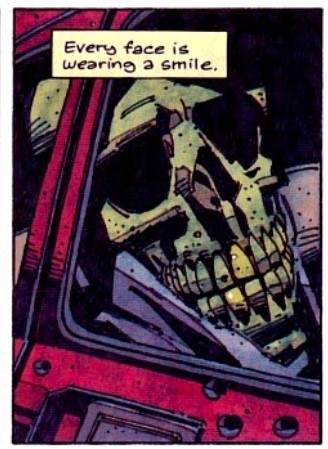

Backgrounds and details become essentialized; every skull we see in the story, and there are a lot of them, is this grinning image of a skull rather than an approximation of a real-life skull. The trees aren’t just pieces of wood but sinister spires piercing the night sky. Colors are muted in a manner that allows the red, blue, and white of the American flag (a constant refrain) to pop up on the page.

The new style McMahon uses here seems to reject the “comics realism” school of thought as a distraction, a chance to avoid dealing with the interiority of the characters. Thus, in The Last American, the outwards reflect the inwards – everything is equally warped, equally damaged. There is no comfort of the perfectly muscled, semi-idealized, Judge Dredd to carry us through the wasteland.

The writing, likewise, treats the reader’s familiarity with the creators’ previous work as a chance to twist the proverbial knife. The Last American keeps offering paths to “plot” – an encounter with the enemy (much gunfire is exchanged); the possibility of meeting more life (possibly moral salvation); the notion of a bond between man and machine (maybe for friendship). Only everything ends up turning away from these familiar paths time and time again. The exciting action scene turns out to involve our protagonist shooting at automated defenses, with no actual danger. The robots are just acting out their programming. There’s no else out there. Life is just a carrot dangled in front of poor Ulysses in an attempt to keep him sane.

Pilgrim himself starts as a shell of a man and just gets broken further as the story progresses. The military discipline is just a façade barely keeping him through. There’s no macho-ing your way out of complete loss. You can’t just will yourself above harm. The final issue ends with a hint of the possibility of someone else being out there… but, at this point, the readers have been fooled enough times. Even if someone else survived the first cataclysm, the chances of continuing life among the radiation and lack of resources are slim to none.

The entire notion of life after nuclear warfare is mocked throughout by the recurring image of a cartoon turtle who recommends the child viewers to seek shelter, duck and cover, etc. as the missiles start flying – an obvious parody of the 1952 animated short “Duck and Cover,” which offered its young viewers rather useless advice on safety in case of a nuclear attack. This cartoon, as well as several other pop culture mentions by the robot Charlie, are seemingly all that’s left from America: the song “New York, New York” and TV show “Doctor Killdare.” All the great works of literature and poetry have vanished, dust in the wind. All that is left is just garbage cartoons. Maybe some comic books

In The Last American (we’re talking about the 1889 novel again), one of the few intact objects that is deemed important enough to be taken back to the museum in Teheran is easily recognized as a Cigar Store Indian: “How these idols were worshipped, and why they are found in little shops and never in the great temples is a mystery. It has a diadem of feathers on the head, and as we sat smoking upon the deck this evening I remarked to Nofuhl that it might be the portrait of some Mehrikan noble.” However one imagines the end of the American project, it seems nothing much will come of it. All that’s left are pop-culture gags.

That’s the true horror of The Last American, not just death of the self, or even death of the many, but the sense of utter annihilation, the notion that nothing we do will have any meaning in the end. Because, eventually, it is other people who give meaning to what we do. Hell might be other people, but heaven is quite the same. No person is an island.

I’m thinking, as I’m writing this, of all those billionaires who make plans for life after the end, who think of the continuation of human existence in their bunkers with their water purifiers and canned goods and, possibly, a collection of embryos. Even when they are not American-born, they seem to be the apotheosis of American individualism – no one can more rugged than the last American, the last person to survive who will prove his superiority to others. When the President volunteers Ulysses for the job of “Apocalypse Commander,” he thinks he’s doing him a favor. He allows him a chance to survive, to “exact vengeance.” He allows Ulysses to keep playing the part of American soldier. What he actually does, though, is damn the man to utter ruin.

There’s no life alone. The Last American is broken because the “last” part of the title is more important than the “American” one. A person cannot live alone, not for long, not if they wish to remain whole. I’m not even talking about the obvious physical needs of society, things do fall apart without constant care, I’m talking about the wellness of the individual. The Last American is a cry of rage and anger at those who would think otherwise, those who are the true “great male narcissists,” who believe that their life on the scale is equal or greater to the life of everybody else. These are those who don’t recognize the humanity in anything besides the “self.” If a broken statue stands in the desert and nobody sees it, does it signify anything?

In many ways The Last American is a work of its time, not many people today would recognize Doctor Kildare for example, but these things do not constrain it. It is of its time because all works of art are; it is also above its time. The emotions that made it work thirty years ago are as valid as they are today and will probably continue to be long after. For all its grim subject matter and grimmer attitude, it is a work of beauty illuminated by passion and crafted by masters of the art that appear free from their old commercial shackles. It is a work to be read carefully. Until death, and possibly even after.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply