Ordinary people who gain extraordinary powers have been staples of the superhero genre since its inception. The 1960s offered an orphaned teenager who gained arachnid abilities from a radioactive spider. More recently, dramatic offerings such as Heroes and Chronicle refocused the narrative. The former, especially, thrived on its dark implications: a government conspiracy, the forcible wiping of memories, and a spate of gruesome killings. In much the same way, superhero comics and films have gradually skewed darker, favoring grim and grimy stories and locales over colorful caped crusaders. Dean Beattie’s as-yet-unfinished comic book Random Trials (2013-2015) sits neatly in the middle. Violent and bloody, with much to say about conspiracies, it also relishes vibrancy, from its visuals to its dialogue. More than anything, it offers a refreshingly down-to-earth and undeniably British take on an oversaturated market.

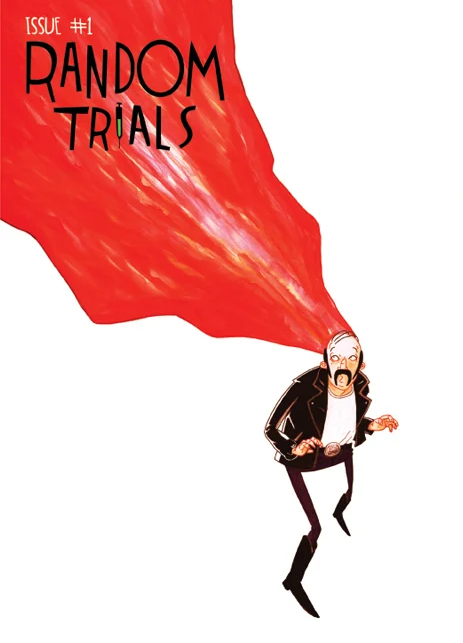

A midnight snack run on London’s Knighton Estate turns violent when Charlie Cooper encounters three would-be muggers. The usually mild-mannered Charlie unleashes a whirlwind of superpowered rage, quite literally tearing the muggers to pieces. Terrified, he hurries home, only to be further set upon by a team of special operatives. This time, Charlie discovers not only superhuman strength, but also an uncontrollable pyrokinetic power. Seeking refuge with his only friend, Charlie finds himself embroiled in a government conspiracy involving drug trials and clandestine human experimentation. His chance of survival lies in the hands of two strangers, one of whom appears to know far more than he cares to admit.

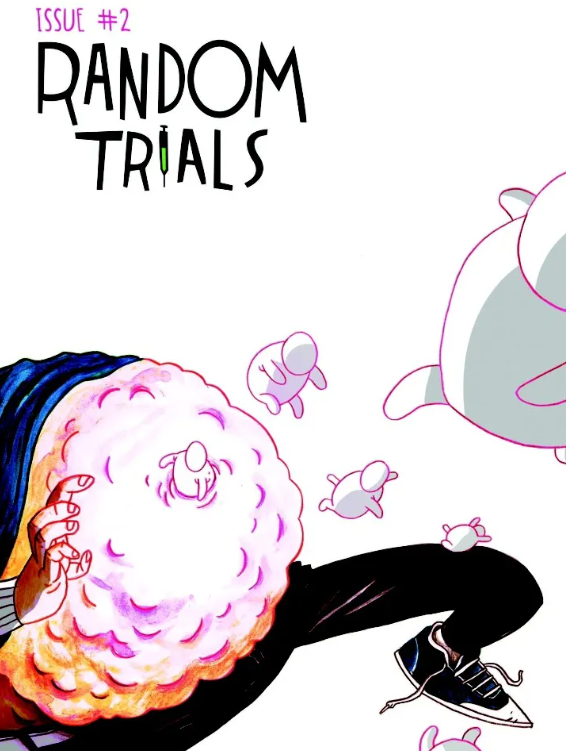

Much of Random Trials’ success is down to its characters. Charlie offers self-deprecation and an almost embarrassed reaction to his newfound abilities. His relationship with Snakebite – an Americana-obsessed conspiracy theorist with an unflinching loyalty to his friend – forms the basis of the comic’s warmest, most endearing moments. Additionally, we have Mary and Norman, respectively described by an antagonist as “a fat girl and a bloke in a pervy raincoat.” The latter fits the bill for the archetypal bumbling Englishman, somehow afforded far more power and influence than he deserves. Mary, meanwhile, is a straightforward, headstrong joy. Perhaps the best of the bunch, however, is Lewis. Introduced as a depressed office worker, he too discovers a superhuman ability. This one involves tiny, featureless, chubby figures who pop out of his navel at crucial moments. His pregnant belly ripples with the eager little creatures, who spill across the cover of the comic’s second issue.

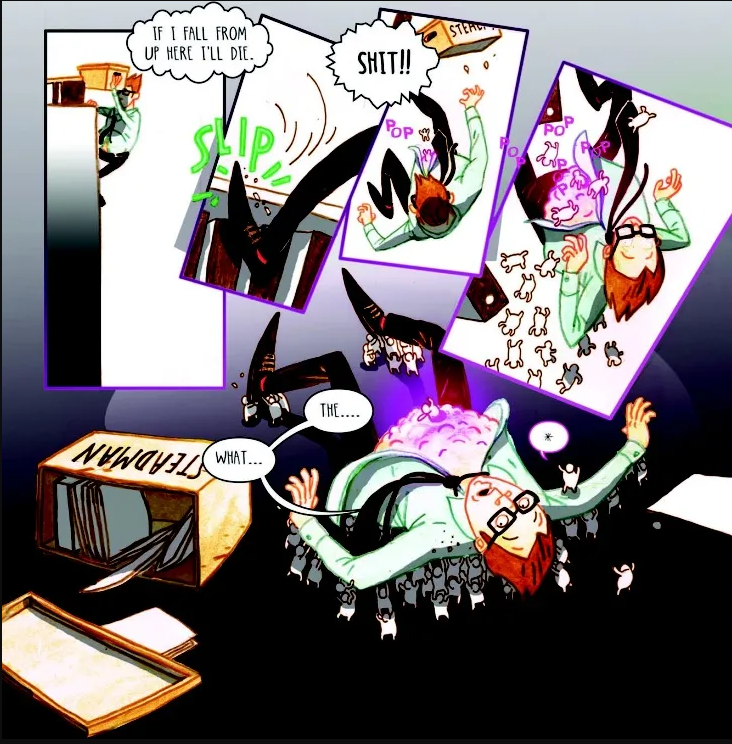

Beattie’s portrayal of Lewis’ ability is not the only memorable image. Created with a mixture of acrylic paints, color pencils, and Photoshop, the art is consistently vibrant and inventive, favoring bright colors and visual humor. Despite the gruesome nature of certain scenes, the tone is overall light and inviting. Beattie also favors classic comic book onomatopoeia; Charlie tackles villains with cartoon KRAKs and CLOKs, all the while sporting a Batman belt buckle (perhaps Beattie has a preference for superheroes more Adam West than Christian Bale). Most exciting, though, are the rare moments of the destruction of the comic’s format. In the first issue, Charlie pushes an assailant so hard that the margin shatters. In the second, as Lewis falls from a great height, the panels tilt and tumble with him. The characters’ influence on the format gives the comic a real personality, and it is a shame that these moments are few and far between. An exploration of these superhuman abilities’ impact on the universe – and, by extension, the characters’ interactions with Beattie himself – would have been fascinating: a sort of dry, British take on Satoshi Kon’s Opus (another sadly unfinished work).

Another bright spot is Beattie’s patent affection and warmth for British culture and, more specifically, humor. It would be impossible not to conclude that Beattie is a British writer; his keen eye for comic detail – be it an unseen youth’s creative vandalism of a sign which now reads “ANAL STREET”, or fridge magnets rearranged to read “ARSE” – enlivens every panel. His dialogue, too, is mostly perfect, striking a balance between deadpan and absurd. Particularly memorable is Lewis’ benign, almost cheerful acceptance of the “little white people” living in his belly, which, of course, unsettles the poor paramedics. Moreover, Beattie manages to find genuine warmth and humanity amid the silliness and slaughter. Exhausted, Charlie and Snakebite snuggle up together on Norman’s sofa. Norman’s mother happily provides tea and biscuits for her son and his surprise guests. Despite finding herself in the midst of a covert operation, Mary is uncritically depicted taking the time to carefully select a tub of the unhealthiest, most tooth-rotting ice cream she can find. These moments are juxtaposed with the impending threat of bounty hunters and government officials’ nefarious plans. The villains, too, are allowed light-hearted moments; all the better to blindside us with bloodshed.

Some of the humor misses its mark, though. Snatches of dialogue from an unseen soap parody infamous moments in British TV history, but the joke was tired even in 2013, the characters’ dialect too exaggerated to be funny. Later, Charlie’s superhuman rage prompts him to decry the “benefit-scrounging, hoodie-wearing, fatherless, lazy” muggers. Granted, he is mortified, but the implication here is not that he does not hold this opinion; rather, that he should not have voiced it. Charlie’s low opinion of the young people on the estate is arguably an astute observation. Despite being in the same situation, he still views himself as separate and superior. Coupled, however, with the EastEnders pastiche, this moment appears less a clever unpacking of classist (and implicitly racist) rhetoric, and more an example of Beattie’s shaky satire of working-class Britain. Thankfully, these moments occur early in the first issue, and Beattie’s observational humor improves exponentially. Considering, though, that these jokes appear so early on – the soap opera joke is on the very first page – readers would not be begrudged their discomfort. Rereading in 2022 necessitates a willingness to push past this rough patch, secure in the knowledge that Charlie’s story is worth it. Sadly, we may never know how Charlie’s story ends. Of the five planned issues, only three have ever been released. According to Beattie, issue four’s pages are penciled but not yet colored. The series was funded via Kickstarter and Indiegogo but was unfortunately not profitable enough to justify continuation. Beattie has therefore understandably been focusing his efforts elsewhere. Random Trials began almost a decade ago, and with no new issues for seven years, we may have to resign ourselves to never seeing the end, which is a real shame. While Beattie may not have revolutionized the genre, Random Trials remains a cozy, compelling, and often hilarious read.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply