Eddie Ahn, author of Advocate and Executive Director of Environmental Justice (EJ) organization Brightline Defense, is a busy, busy man. When we were able to connect (after an initial scheduling error on my end), he was at the tail end of a book trip out to Colorado– one stop in a series of talks in cities like Portland, Los Angeles, Boston, Seattle, and Sacramento.

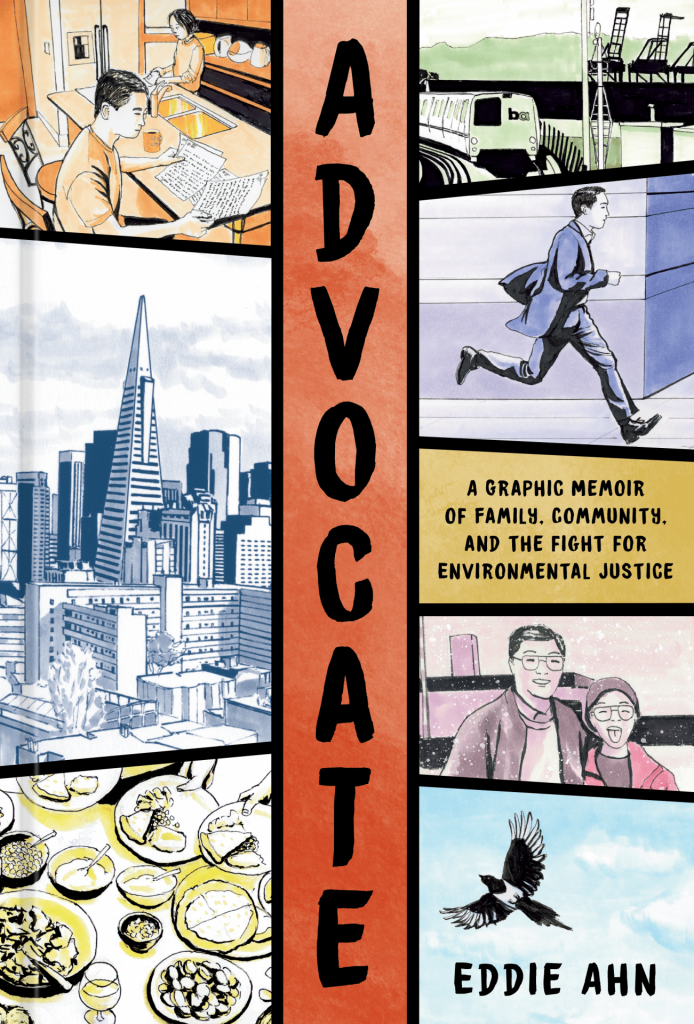

Advocate is Eddie’s graphic memoir about growing up as the child of Korean immigrants, his ventures into community law, his long, intense journey heading an Environmental Justice non-profit in San Francisco, California.

I knew of Eddie’s Brightline Defense work first, from my work as a Community Planner at a non-profit organization that has collaborated with Brightline Defense. I didn’t know of his comics work until I ran into his table at SF Zinefest in 2021, and bought a beautiful blue-wash print of the downtown San Francisco skyline. Brightline Defense, as an EJ organization, is, in his words, at “that intersection between environment, economy, identity– trying to get at how communities are affected by their surrounding environment.”

In this conversation, Eddie and I discuss his unique vantage point as ED of an environmental justice non-profit, and often at the frontlines, growing in parallel to his practice as a comic book artist, to zine culture, representing real people in his comics, his family’s reaction to his work, and what’s next.

This interview was shortened and condensed in the interest of space.

Amy: What actually prompted you to start translating the non-profit EJ work that you’ve been doing into comics?

Eddie: The fundamental conflict that’s in the comics is essentially my parents hating my non-profit work. They were not fans of it for decades. It was tough because I think a lot of it came from a place of love, and understanding the world that is perhaps more transactional than what I was doing. They had run liquor stores since my childhood and their worldview was shaped by that mentality of you making what you can in life: find the profit margin, and that’s essentially your cut. Why would you want to go do this work, which is trying to be more generous? Why try to give more to others than what you would get in return? That was a very hard concept for them. So trying to have these comics, translate those community interactions, the larger goals of what we’re trying to build for, for a very visual style of storytelling: that was the intent of creating these comics.

Amy: Tell me about your initial journey in comics and graphic novels: was it something you were always interested in as a youngster? Was there a certain point when you started to take it more seriously and commit to making comics more consistently?

Eddie: I always loved drawing as a child. My parents ran liquor stores and as a kid, my sister and I would hang out in the back room of that liquor store, drawing on scraps of paper, whatever was available, really (on cardboard boxes). Back then, there was something called paper– they were these big sheets of paper with perforated edges and you could create a big scroll. So even the way the format on which you draw really influenced the way I thought about graphic storytelling: it’s something I always had a passion for because you’re only limited by the expanse of the page. And if the expanse of the page is bigger, all the better.

I did a newspaper strip for the school newspaper in college. It taught me some of the storytelling beats of trying to tell a more linear story. This was as social media was being created– I think our attention spans and how we consume information has changed a lot. I drew a lot of self-published comics, fictional stories after I graduated college until my early non-profit years. Those comics, whether a comic strip or comic book issue, were great, but it was also hard to produce against the timeline I was on, meaning I couldn’t produce a single monthly issue over a single month. I was essentially a one person army trying to produce it all. It was only during the pandemic, when we were under shelter in place mandate, and I had theoretically more time in our hands that I could sit and draw the autobiographical comics that are now collected in the graphic novel that is today Advocate.

The early years in which I started drawing autobiographical comics was 2016-2020, but I never published them anywhere– just held the pages to myself, not really sure if there was an audience for it. I came from zine culture too: there are a number of Bay Area comics festivals, like Alternative Press Expo (which no longer exists), and SF Zinefest, which is still flourishing today. These festivals were really a way to create your own art, handstaple the booklets yourself. It’s a very Do it Yourself culture, and then you try to market amongst 100+ other artists. A lot of it is lessons in creating something against the deadline (the festival’s deadline) and figuring out how to put it out into the world. Those fiction stories are very nostalgic, and it’s something I’d like to return to, but it’s really the autobiographical comics where I honed my craft.

Amy: I’m really interested in what you said about being influenced by zine culture, especially in the Bay Area. Can you speak to how it influenced your craft, and how you think about designing and creating story altogether?

It took a lot to get comfortable even with the idea of autobiography because I felt like it was very self-involved. I don’t know if my life is interesting day-to-day–I would much rather write about an angry talking turtle trying to sell coffee, or a series of wishes that would remake the world, or create a science fiction dystopia. Those were the biggest concepts I was working with, so to write a comic about non-profit work… I was like eh.

Zine culture got me comfortable with the idea. Zine culture is very grassroots. The communities you meet are great too. They prize diversity, they really love indie storytelling. For myself too, my biggest ambition for the autobiographical comics when I first started was oh maybe this would land with Fantagraphics. It was not to land with Penguin Random House. That all said, if I didn’t even reach that stage of Fantagraphics or Penguin Random House, I was totally okay with promoting through zines, having these comics reproducing them through a copy machine and stapling the booklet together, and ultimately, presenting it to my parents. The original goal of these comics was trying to explain what I do for a living in a visual sense for my parents, who are not native English speakers. There were things that were difficult about zine culture, like the constant scrappiness of it, the overall sense of too much information, and can you really stand out amongst so many other artists. At the same time, those were its strengths too. I have a lot of nostalgia.

Eddie: I remember the first time I met you was actually at SF Zinefest, so I totally remember that! So just to get a little bit into the book, and the content of the book: we got this interview going from the book event you held in San Francisco Chinatown, where you had, as an interlocutor, the Executive Director of the community-based Chinatown organization I work at. You spoke a lot about the important political education that was being done by Advocate, like using it to explain what Environmental Justice (EJ) is. I love to hear you talk about how you think about comics as a tool of political education. How does that work for you? What’s the intention behind it, and has it been successful?

I’d like to think so– that it’s been successful.

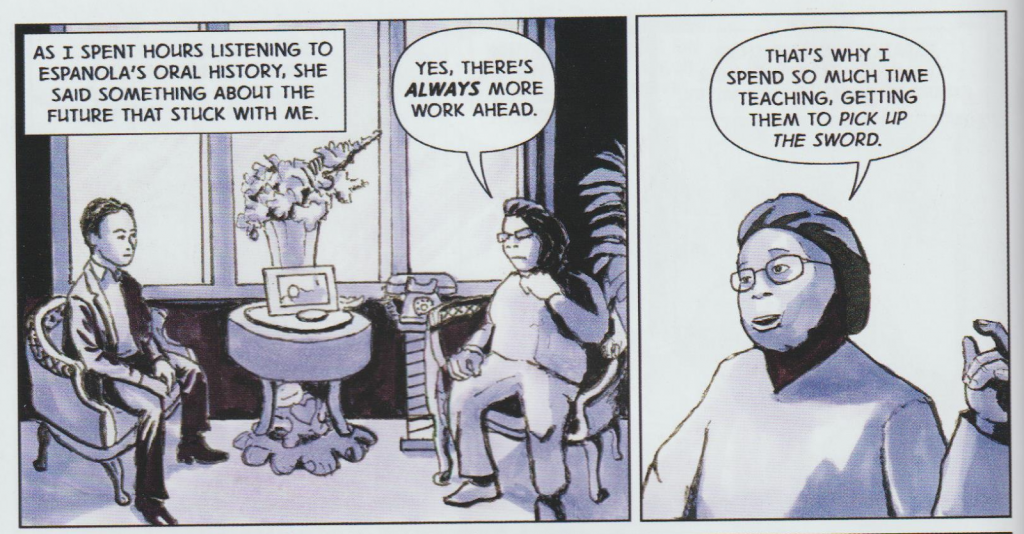

There were two components that I was always thinking through when creating these comics. One– part of the reasons why it’s drawn in such a hyperrealistic manner and off of photographic references is I wanted to portray individual leaders very accurately. People like Dr. Espanola Jackson, who was a longtime activist in Bayview-Hunters-Point. I did present Advocate before her family at a yearly celebration of her life that they do in the Southeast, and they loved seeing that representation of her on the screen, in that manner. I mentioned stuff like how purple was her favorite color and those pages are drawn in purple, and they just love that. For me, cartooning can take on a lot of different forms. If you look at the illustration styles of, say, Charles Schultz’s Peanuts vs. Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, it’s very stylized linework to represent the human figure. That’s not what I did with this book in part because I wanted it to show how communities are built by these very unique personalities that are recognizable by people around them. That was the first component.

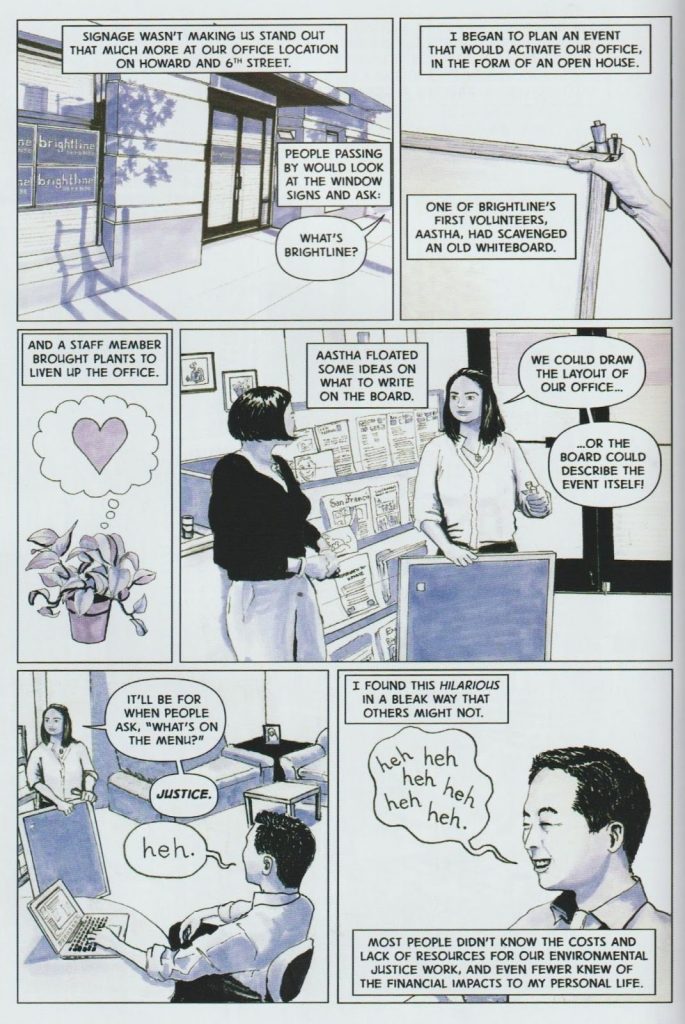

The second component was built around political education itself. I never wanted the comics to feel preachy. It’s done through the lens of personal memoir. There’s also another saying that the personal is political. I do think that’s true in something like this, where doing non-profit work is extremely difficult. It’s emotionally taxing, and oftentimes the hours are very long, especially when what’s portrayed in this book is essentially myself, and maybe another part-time employee, trying to build up the non-profit in the early days. But I guess part of that scrappiness and underresourcing is a reflection of the systems around us too, and what we value. Comics, in some ways, was a more simple way to portray that. Like, if you see myself running like a maniac down the street trying to make the next meeting, there are a couple of ways to ask why that’s happening: oh gosh, Eddie’s working too hard, why is he working too hard, is it because he doesn’t have enough support around him? Or that haunting question of is it ever enough too? I think it’s done enough in terms of education, but I never wanted to feel like it was hammering the themes. If you choose to interpret in that way, great. And if it just sails over people’s heads and they just don’t get it, then that’s ok too. It’s always welcome to interpretation.

Amy: You mentioned at the event that your mom had called you up after she read it, and it seems like it got through to her.

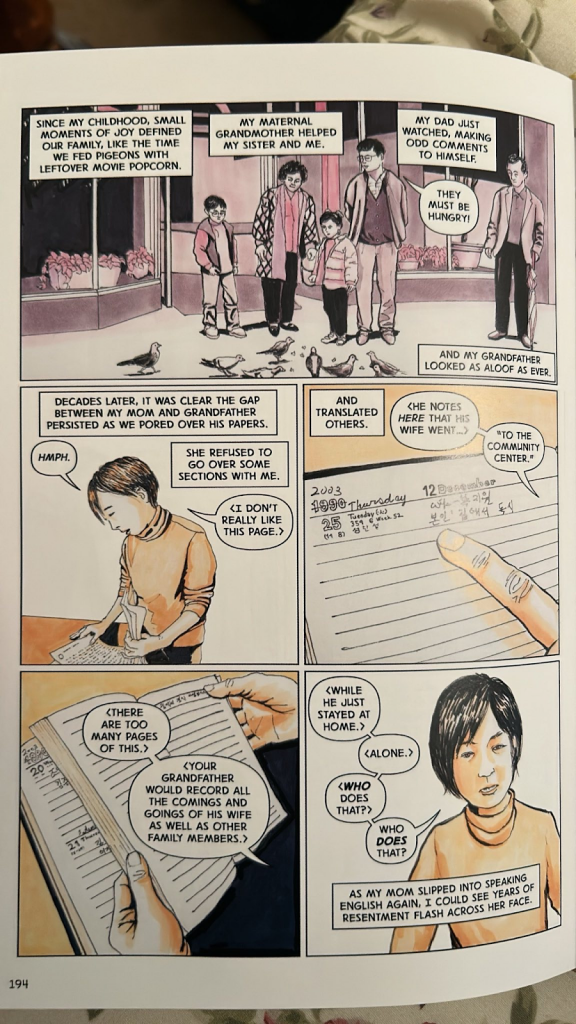

Eddie: I think that ultimately she was very touched. Initially, I was very worried that she was going to be sad or angry about the way that she was portrayed in relationship to her father, my grandfather, who’s also in the book. The reason why I wanted to show my grandfather and even his own memoir at various points in the book was reflecting upon notions of service, notions of trying to build something for yourself, and for people around you. What the book shows is that my grandfather was considered a failure by his surrounding family. It’s very painful to my mother, my aunts, her sisters, and he knew that– that’s one of the tragedies. And he couldn’t help himself. I think a lot about, as I was creating this, how my mother wouldn’t appreciate me portraying all of that. The good news is that several months after the book was published, she read it, she said I loved it, she cried. She read it again, and even in the second reading, right after. I think, for her to read and reread it and appreciate it… I thought she would be really upset about portrayals of family, thinking about her own relationships. What she was most moved by was the idea of a non-profit worker and how underappreciated that labor was, and for me, that was the entire point of creating the book. I’m glad she said that to me because I think a lot about what I was doing when I set out to start this, and for her to even say that was, I felt, a good acknowledgement.

Amy: I appreciate that you said that one of the core intentions was to portray individual leaders very accurately because in memoir classes, there are a lot of craft discussions on what it means to include personal people in your life, and the politics in how we’re representing them. You incorporate so many people in your book: I saw one of my coworkers in the book, I saw your staff and community organizers in the book and it’s quite beautiful in that it becomes not just about you, but about the community you’re working in, and the organization that you’re working in. The question that I have is whether you feel if this could’ve been a book that is less tied to Brightline? Could this have been a book just about Eddie?

Eddie: That’s why I struggled with autobiography so much. Even as I was creating the original outline for this project, the intent was actually 10 short stories around 10 individuals. So it was not to be myself as the protagonist, following my own personal journey (whether it’s a rise, fall, rise again). As I was working with a New York City publisher, I realized that they really did want a more Western form of storytelling, centralized around the protagonist and following their arc. I think that there are reasons why that narrative succeeds more at the end of the day, but as an artist, what I had was a crossroads: I had a choice to pursue those ten short stories, or be okay with reformulating what I was already creating for Instagram to what became seven chapters with a prologue and epilogue. At the end of the day, I’m happy with the final product. It’s a very personal choice for every artist to make, but for myself, I think it worked out well. I think it really helped focus the storytelling and make it about certain arcs.

The other hard part is the labor of comics is very consuming– it just takes so long to produce this stuff. Having a more kind of structured narrative helped with the production of it all too. Originally, when I had the 10 short story ideas, it was supposed to be 100 pages total, 10 short stories with 10 pages each, and then when I signed the book deal, they said I needed to produce 100 more pages. And if each page takes 20-30 hours, it was like… a huge slog to get through for the next year, year and a half. By that time, the contours of the book were set, and I knew the direction that I was going to have to run in. I’d like to think that you get one project done and you can figure out the second project a lot more quickly as a result of having gone through the first project.

Amy: Oh, so you’re working on a second book right now?

Eddie: I am. To go back to the discussion around how the first book was drawn, I’m trying to change up and not draw from the same photorealistic manner. If you’ve taken a graphic memoir class, you’ve probably read Art Spiegelman’s Maus. I’m using animals to portray different people for different storytelling reasons. Art Spiegelman used it to portray the predatory nature, the guards, the victims of the Holocaust. For myself, it’s actually to portray the personalities of people involved, but also to protect their identities. It’s a core reason in the era we live in– I’m very aware of how this stuff gets out in the public space. I want people to be protected if I’m telling their stories, too. I don’t think someone like Dr. Jackson would mind, or her family. In fact, they loved it. But in today’s environment, with people doing the work right now who are still alive, I want to make sure they’re in a good place.

The quirky thing about the first book is that I’ve still been touring the country, talking at a lot of bookstores, schools. Usually, a book tour arc is within four months of publication of a book. The book was published in April 2024. I’m talking to you from Denver right now, having done a decently attended bookstore last night. I’m going to Boulder tonight. This book has relevance in today’s era in ways that may not have been true a year ago. I think that it’s only when stuff gets taken away, whether it’s freedoms, commitment to community, or even non-profit work itself when you ask is it valued or not? Is it going to get targeted in this new era? People realize, oh gosh, maybe there was value in it all. I do think seeing the people all I have on the road has given me a lot of heart and helps fuel future work I have. The pages are drawn, and it’s going to be published on Instagram, so I guess I’ll see people’s reactions to that, too.

Amy: I remember during the event, you mentioned the response of people on Instagram encouraged you to keep going. I’m also wondering in terms of how it might’ve affected the story and the narrative arc of the story. Even the constraints of Instagram as a platform– you can only put so many pictures up. Does that influence what you’re thinking of, in terms of what you’re thinking? The colors? Would love to hear more about, narratively speaking, how posting on Instagram influenced how you were thinking about the stories initially.

Eddie: In the early days, in 2020– my recollection is that you couldn’t post more than 10 pictures at a time. Just 10 panels. In early days, I stitched together a seamless reading experience. I took a lot of extra effort on Photoshop to do so. It made the comics engaging for an online audience and helped build it out over a short period of time. If you think about 10 panels, it’s not a lot in comics, if you’re trying to tell a graphic novel. What I tried to do was stitch together a short story on Instagram over a series of posts. I think that the audience followed it well enough that they’d be able to go back over the homepage, start with the first page, start reading onward. But I’m also very aware that you’re competing against other creators, artists, etc. So it’s hard to put that content out in a way that people will consume and the information remains sticky with them. Those were the constant challenges I was balancing. But at the same time, each post centered around comics seems to have decent meaning for the audience. The comment section was always really helpful to read and understand how people are consuming this. Is it sticky or not, at the end of the day? Is it persuasive or meaningful for people?

Amy: Were there specific themes that you would’ve added or adjusted to make it stickier for people?

Eddie: Yes, it’s the sequencing of comics, too. As I give a lot of classes on cartooning or graphic novel making with middle school and high school students. I always try to emphasize to them that it’s not about the art inside the panel. It’s how the story moves from panel to panel via the gutter, and the blank space between the panels and comics. With social media, you have to negotiate that well. If you’re constrained by 10 pictures per post, that means that you have to really think about moving enough of the story in the span of 10 panels or less that will ultimately make the audience want to comment or reshare or like it or whatever. That said, the reaction to the comics shared on social media is very nice. Of course, I’ll get the occasional angry person, but that’s fine. What I’m also very worried about is being driven just by social media, too, that doesn’t feel healthy. I talk to a lot of artists and creators about this as well. It can be either a black hole where you’re just throwing stuff into the black hole and not sure what you’re getting out of it– or it can be an endless treadmill, where you do get a nice reaction but it’s just this endless maw that you’re feeding, and you’re not quite sure where it’s going. For me, at the end of the day, as an artist, I wanted for it to be in print, whether as a zine, or independent comics publishers, or more traditional publisher. I just wanted that tactile feeling of reading a page, turning it, absorbing it, perhaps. Absorbing it, and then wanting to turn the page back. Rereading the page– that would be the ultimate success for myself as a cartoonist, having the reader do that.

Amy: Yes, this was not a realization I had until I went to your event and you passed around your sketchbook– and I realized how analog your work was! I think, looking at it on social media, there’s a lot of digital platforms now that people use, and they can adjust it so that it seems more analog. But yours was incredibly analog– at the event, you auctioned that beautiful picture of a bird by literally ripping it out of your sketchbook. You use felt marker pens to color, and continue to most of your linework on paper before uploading. I was wondering if you could tell me a little more about this as a choice. What it means for you to continue doing work like this when so many people have started working digitally.

Eddie: I get made fun of by professional cartoonists, actually. This happened more recently in the past few months. I don’t mind– I mean, it is kind of fussy, the way I draw. It’s a function of having taught myself how to do that process for so long. I’m self-taught almost entirely as an artist. Everything I know about anatomy, perspective, coloring, even framing graphic storytelling– it’s all stuff I learned over the course of two decades. The introductory art course I took in college was about using different mediums– you learn how to use charcoal, oil paints. But it wasn’t about the actual act of drawing and telling the story through comics.

I do think that these cartoonists who make fun of me for my hand-drawn process are right. There’s a reason why people draw digitally with an Apple pencil on Procreate. It’s faster, it’s more cost-effective, and, even in the more succinct words of someone I really respect, you don’t win any awards for drawing by hand. But at the same time, there’s something that’s instinctive about it: I like working across a page. I know what I’m good at at the end of the day, what I’ve become skilled at. I’m weighing right now how much to continue doing that process given my limited time versus trying to scale up a new process like digital drawing. I’ve been experimenting lately with iPad and Apple Pencil and buying some tools to go along with it, like a nice little digipad to help you do shortcuts on Procreate. Even in the last few weeks, I’ve been thinking about it. I’m not that excited about it, and I really want to get back to drawing by hand.

Amy: I think that it’s something with the proliferation of AI, it’s something very precious in being able to do these things by hand.

Eddie: Even the mistakes you make by hand… a mistake made by AI just doesn’t have the same feel. Maybe AI can imitate that in the future. But what I used to be obsessed about correcting, I’m now thinking is the beauty of the art. When I think about the little imperfections, that’s the human interpretation of the world. It can be more apparent through a hand-drawn process than say through a digital drawing.

Amy: Could you speak a bit more as to whether you decided initially on whether this was how you wanted to color everything? How was that process of deciding what color for what section? Like for Dr. Jackson, you wanted to use the purple. And with the parts of the fire, you used the orange, which makes a lot of sense to me.

Eddie: Color was always intended to move the time and mood of the story I was telling, so I wanted it primarily as a technique for doing flashbacks and flashforwards, without exhaustively timestamping everything. Each chapter is easily grounded in one primary set of colors, maybe like tones of green, but then we’ll either flash forward to say it’s a story maybe told in 2009, but will flash forward to 2017, with scenes of my mother in the hospital. Part of this was to get at themes– themes of taking care of one’s family, or building one’s community. I really just wanted for it to be a seamless reading experience rather than jerk the reader back to Fast Forward to December 2017 or Flash Back to March 2020. The textual time stamping was beside the point, which is why I used color in this way.

A more functional reason for using the color was that it was also driven by cost. Copic markers are very expensive. If you buy them individually, it’s about $8 per marker. For myself, I could only buy two or three markers at a time when I was a non-profit worker. That, in some ways, really honed my decision making. Then I could say green could represent my early days out of college, trying to make it through law school, could represent my naivete about the world, my innocence and lack of experience, and trying to grapple with what I thought were the world’s problems. Purple itself– that was a happy circumstance where it was Espanola’s favorite color and I got to draw Espanola using those tones. And then for the era that I was in– It was transitional for me. I was just graduating law school, trying to figure out my way in the world. Purple itself is a blended color between blue and red. It’s a transitional color in itself. I liked thinking through the themes of each era, and then trying to color-code it accordingly.

Amy: The last question I have is around your drawing schedule, especially since you mention you don’t have a lot of free time! What does that look like for you?

Eddie: What’s hardest is doing the events. I do feel that they’re going to wind down in the next month to two months. Denver is one of the last big swings. I’m going to do one last bookstore event in December and that’s going to be in Portland. But beyond that, gosh, I should be really focused on creating the next work of art. There’s two ideas in particular I’ve been working through, thanks to my agent. One is that comic idea I just mentioned to you, and the second is a written novel that I’m working on, so I hope that one of them or both of them gets picked up. It’s always hard to predict. I do think that the entertainment industry and its modes of production… it’s a miracle that anything gets published, it’s a miracle that anybody sees it, it’s a miracle that anybody likes it. It’s a bunch of miracles, all stacked up against each other. That’s me paraphrasing someone in the film industry that talked about how hard it is to make a movie in Hollywood. Yeah, I think it’s the same for publishing. I need to set aside more time to create comics. In the most productive days of the past year, before the book went out to print, I was working a 45-50 hour work week at the non-profit because it’s still very much a fulltime job, and 45-50 hours may sound like a lot, but it’s actually a lot less than then 100-120 work weeks I used to do to try and build it up. That said, if I work that full-time schedule, I just need to be very intentional about finding those 2-3 hour blocks for creativity. That’s after work, on the weekends, it usually amounts to 15-30 hours. 30 hours is a lot, it’s probably closer to 15-25 hours a week spent on drawing on various other creative processes. Photoshop is the least exciting of those. It’s a very kind of focused process.

Amy: Thank you, Eddie! It was so great to chat.

Eddie: Thanks!

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply