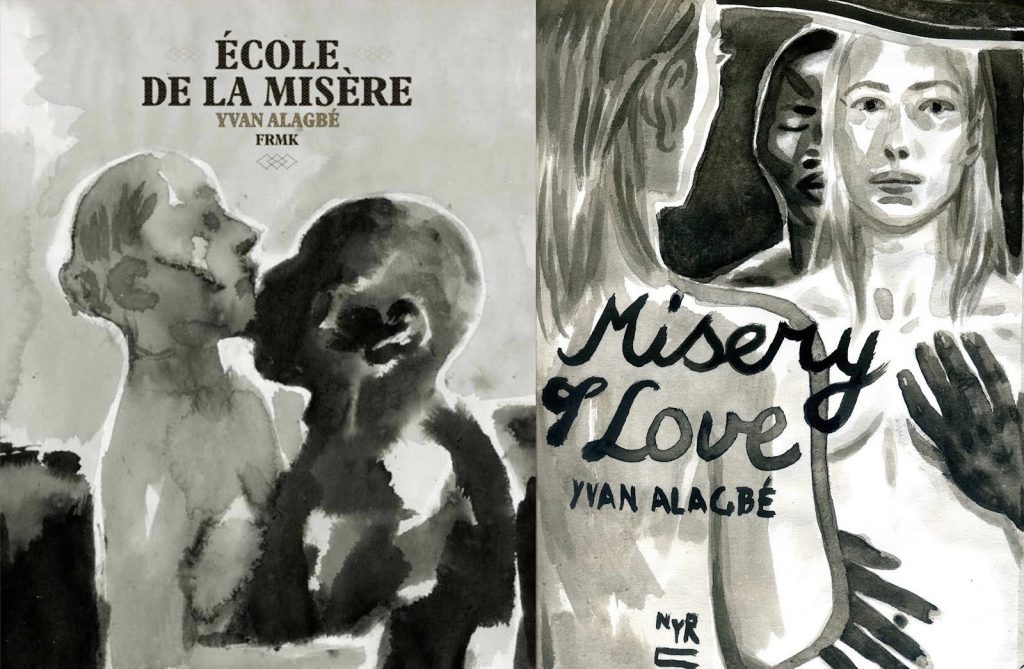

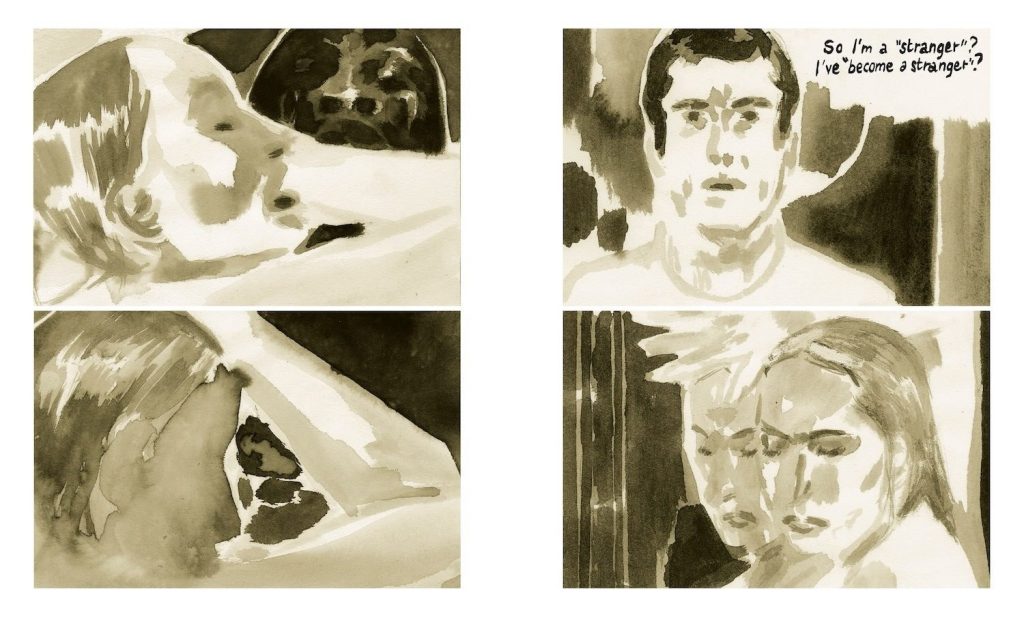

The cover to Yvan Alagbé’s École de la misère (“School of Misery”; Frémok, 2014) is an act of passionate lovemaking. At least, we might infer the passion from the corresponding sex scene, a breathless, staccato affair, though Alagbé’s choice of medium — ink-washes without any underlying line-work — gives it an air of deniability: the (white) woman’s face is hardly legible, the (black) man’s features not at all, disappearing as they do in the heavy blackness of the ink. In their lovemaking, they appear side by side, the woman wrapping her arms around the man’s body, somewhat more elevated than he is.

By the time École de la misère arrives in English — as Misery of Love, published this past July by New York Review Comics, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith — a significant shift has occurred: the couple is no longer having sex; instead, in a different sort of intimacy, they are standing in front of a mirror, the man’s hands on the woman’s breast and belly. Their faces are vivid now, vivid enough that we can see that his eyes are closed while hers are open, that his face is intent, focused, while hers is sober, distant. More notable, however, are their respective placements: the woman appears twice — her body, viewed from the back, and her reflection in the mirror, facing the reader — while the man appears only as a reflection blocked between the woman and her reflection, removed from the reader several times over.

This transition between the two covers mirrors the temporal transition embodied by the book itself. The man is Alain, a Beninese undocumented worker living in Paris; the woman’s name is Claire, and once upon a time she was his partner. They are not new characters, having previously appeared in Yellow Negroes (published in French in 1995, then translated into English as part of 2018’s Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures, likewise published by NYRC and translated by Nicholson-Smith), but, whereas in that book they are still happily (or at the very least frictionlessly) together, by the time of the events of Misery of Love’s their relationship has already fallen apart. The thrust of the book’s action takes place during the wake for both of Claire’s paternal grandparents, as she is forced into close quarters with her family; with this main narrative, Alagbé interlaces flashbacks to Claire’s past — to the strain between her family and herself, as well as to her ultimately failed relationship with Alain.

Misery of Love’s back-cover copy compares the book’s fragmented chronology to Richard McGuire’s Here, a comparison I find noteworthy not because of the structural similarities themselves so much as how these similarities reveal, in truth, key differences in underlying approach. In both the original short and the graphic novel version, Here operates on the same central principle: a fixed base grid (six panels per page in the original, one panel per spread in the graphic novel), depicting the same space from the same fixed angle, with gradually-increasing inset panels of varying sizes, manipulating comics’ time-expressed-through-space. Furthermore, McGuire’s comics work is informed in no small part by the artist’s foray into Zen philosophy, and the outlook articulated by Here is a universalist one, as the specifics of character, of human life, are de-prioritized in favor of time itself. In McGuire, time itself is held up as the protagonist, and all of time is contained within the singular moment; humanity is just a circumstance, a collection of set-pieces. His choice of space — a residential house — underscores the ephemerality of human life: families move in and leave, the house is torn down and built anew, and constantly the reader is reminded that there was life before the house was there, and there will be life after it disappears.

Alagbé’s focus is self-evidently different, as neither ‘time’ nor ‘space’ interests him in the abstract the way they do McGuire; instead, Alagbé’s conception of time is a fundamentally humanist one, contained and contextualized first and foremost in the lives of his characters, who are, themselves, specific and articulated, never archetypal or interchangeable. Though the uniform grid and panel sizing does result in a planarity of time, where no one moment is more ‘important’ than the other, the anchoring point is not a universality but a material political reality.

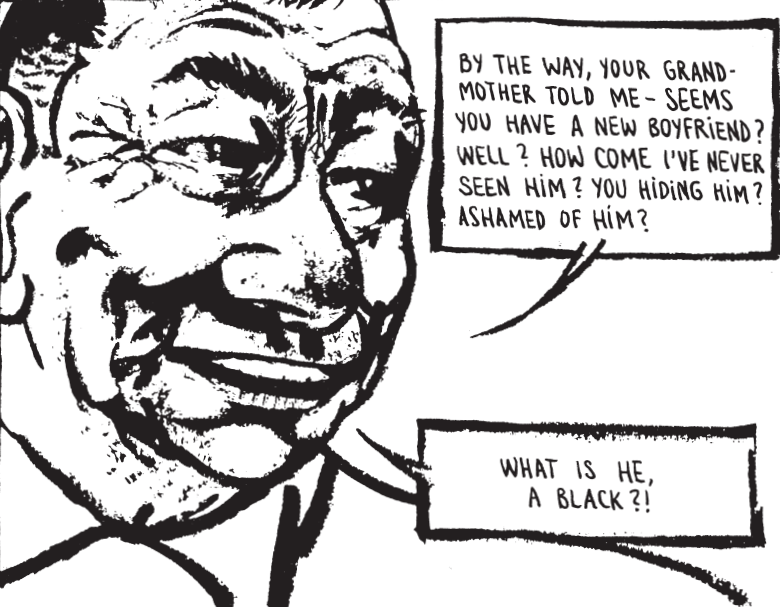

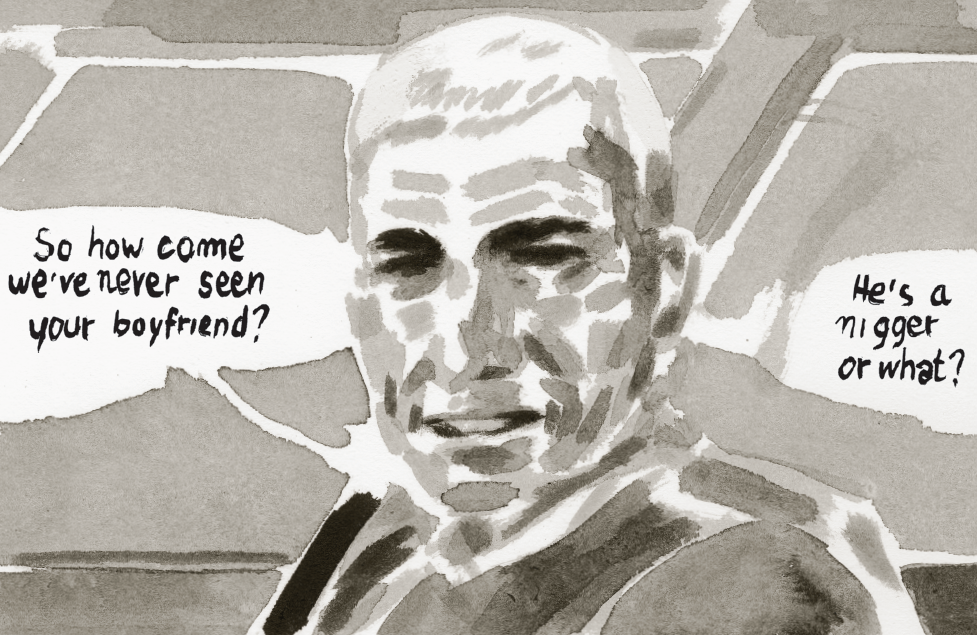

This political reality, of course, is one shaped by trauma, by the way memory becomes scar tissue as it flares up, violently and without notice: the cartoonist does not label each panel with a corresponding date, placing upon the reader the onus to chronologize and infer, thus giving his scenes a sense of totemic importance in their disparity. In Alagbé’s work, memory as a thematic concern takes on an enhanced poignancy, given the cartoonist’s habit of repeatedly reworking, revising, and expanding on existing works: after the serialization of Yellow Negroes in the anthology Cheval sans tête (“Headless Horse”), Alagbé redrew the comic completely for its standalone album publication, following which he revisited the characters in two short stories — “Dyaa,” which appears in Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures and focuses on Alain’s sister Martine, and the as-yet-untranslated “Le deuil” (“Mourning”), which focuses on Claire’s grandparents’ wake, serving as the much-briefer basis for Misery of Love. Through the repeated return not only to the characters but to the same events, the cartoonist evokes the human memory’s function as its own self-editor. See, for example, the following panels from a scene that appears in both Yellow Negroes and Misery of Love, in which Claire’s father finds out that she is dating a black man:

Not only does the change in layout make the moment literally ‘bigger,’ adapted from the earlier book’s six-panel grid into the present work’s languorous two-panel rhythm, but Alagbé carefully chooses how to end the scene: in Yellow Negroes he goes on to show the father’s response upon finding out that his offhand joke turned out to be prophecy — he is genuinely, viscerally appalled — whereas in Misery of Love he cuts away after Claire’s answer, not giving the father time to react. And yet most significant to me is the change in phrasing, not only because the dialogue is substantially streamlined in the latter book but because of the change in racial slur. Though the change itself originates not in Alagbé but in Nicholson-Smith’s translation — the original French employs the same word in both instances — we nonetheless see here a striking reflection of memory’s capacity for distortion and heightening, ‘self-editing’ to render the implicit explicit.

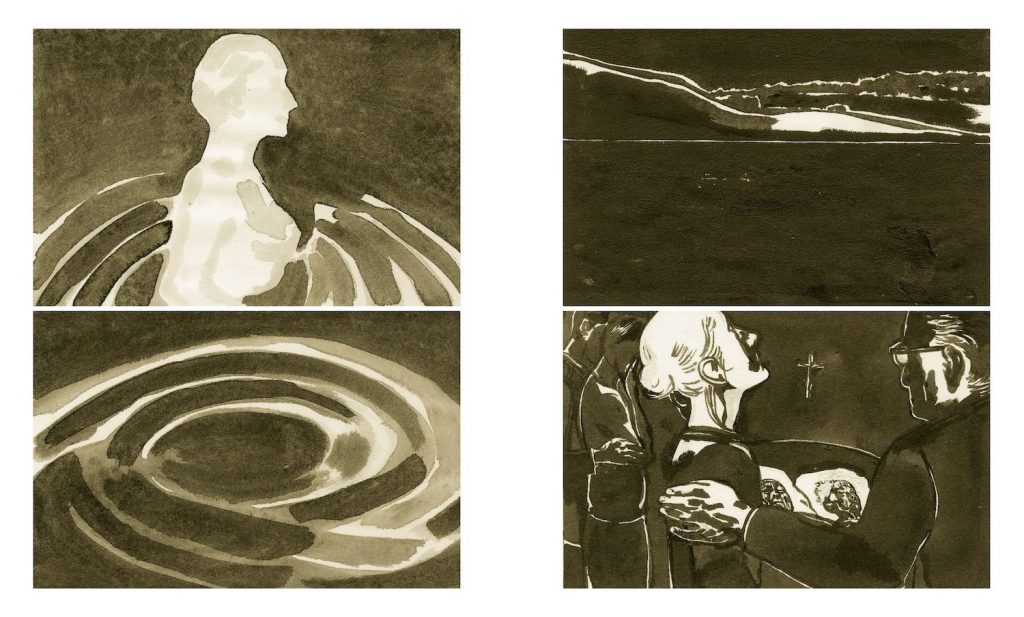

In addition to the change in page layout, the shift in focus is complemented by a change in tools, employing ink-washes instead of drybrush ink. It’s a change that makes immediate intuitive sense — taking place over a short span of time and focusing on Alain’s entanglement with a French-Algerian former policeman who tries to help Alain and his sister as an attempt to make amends for his abuse of his fellow Algerians in the name of French loyalism, the story of Yellow Negroes warranted a sense of energy and urgency; Alagbé’s lines are texturally harsh yet selective, often leaving surfaces unrendered or backgrounds unspecified. The benefit of the drybrush in this regard, simply put, is that its application is binary, quite literally black and white: either the ink is there or it isn’t. In Misery of Love the whole of the page is overrun by ink, more often than not, and the question becomes one of shades of gray, of values of light and dark. With Alagbé’s ink-washes, there is less of a distinction between foreground and background — the process is holistic, defined by the accumulation, while the individual brush-strokes become invisible. This allows Alagbé to venture deeper into expressionism: as the funeral attendees file into the chapel, they look less like people than translucent ghosts; in one panel during Alain and Claire’s sex scene, their bodies lose their bounds completely, fading away into vague swatches, legible as sex only through the context of the surrounding panels.

This transition to ink-washes results in a ruminative atmosphere, simultaneously soft and heavy. I cannot help but tie this into one of the two main themes of the book, being, naturally, race — more specifically, white France’s regard of its own colonialist past and how it informs its systemic present. In Yellow Negroes, Claire appears as a fairly simple (though nonetheless positive) character, an emotional and practical support for Alain, and, though she certainly ‘pays a price’ for her relationship with Alain, it is more on the social level, most predominantly in how her family sees her, than anything else; to Alain, race means everything — his livelihood, his safety, his legal status — whereas to Claire it is a second-hand presence. The Claire of Misery of Love, however, is decidedly more complicated. As the story unfolds, readers learn that her recently-deceased grandparents previously lived in French Cameroon, where they ran a brothel; it was this money that made the family’s affluence possible, at least up until Claire’s virulently-racist father cheated on her mother with an Arab woman, squandering much of the family’s money while also refusing to take responsibility (at one stage he accuses his parents of not supporting Claire, until his brother-in-law reminds him that he didn’t fare much better in this regard). Here, Alagbé furthers the thread of sex-as-sublimation-of-race embodied in Yellow Negroes’ Mario: Claire’s entire lineage is contaminated by interracial oppression embodied on the sexual plane.

In this context, it’s worth observing the sex scene between Alain and Claire, which sees the book’s only divergences from Alagbé’s rigidly established realism. Twice during this scene, the sex breaks away from literalism into symbolism, represented as a physical match between human and beast, drawn in a sharp, uniformly-weighted pen; at the same time, however, the scene is also the only instance where panels contain more than a single point in time, albeit without any inset-panel borders like in McGuire: as the couple has sex, Claire’s grandparents are shown sitting ghostlike in the background. Sex, then, becomes paradoxical — simultaneously freeing, as for one fleeting moment the partners are unencumbered by the social decrees of humanity, and a prison, as the ghosts of generations past sit in and supervise in implicit disapproval.

For Alagbé, son of a white French mother and a Beninese father, race is a state of fundamental ambiguity and existential suspension: “When I lived in Benin in a neighborhood where there was a mix of ethnicities,” he recalled, in a 2019 interview, “I was considered white. When I tell this story in France people are amused because for them I’m black.” This perhaps explains the racial-moral ambivalence in his work, and his reluctance to equate marginalization — or even support of the marginalized — with an immediate claim to morality. Misery of Love pointedly chooses to complicate Claire’s moral stature in the eyes of the reader: as a teenager, years before she will meet Alain, she is shown having an argument with her grandfather, during which she proclaims, for no other reason but to provoke him, that she will marry a black man. Her grandfather, in response, slaps her. The impact of this moment is explosive, as the reader is violently forced to consider Claire’s love for Alain, at least momentarily, as stemming from filial rebellion, a conflation between romance and transgressivism.

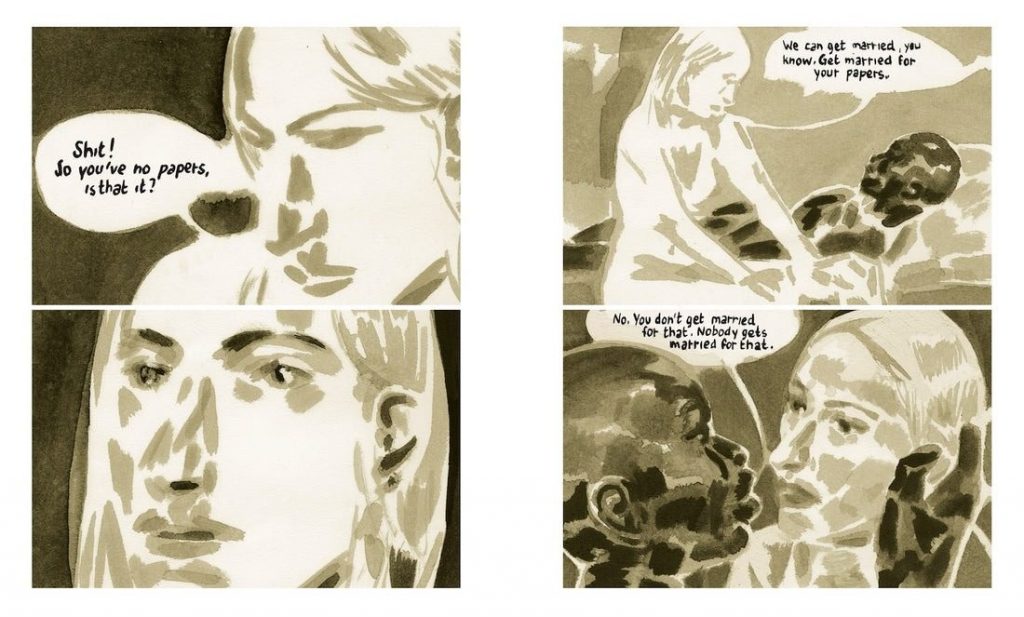

The cartoonist goes on to show the limits of Claire’s understanding and insight: the subtle divergences between Claire’s view of Alain and what Alain cannot afford to say out loud. In a scene that appears in both books, Claire offers to marry Alain so that he can get his citizenship and working papers, but Alain refuses, saying that marriage must be a product of love, not mere practicality. Again, note the cartoonist’s psychological approach to editing: in Yellow Negroes, Alagbé shows him how Alain really feels, as he muses to himself in narration, You’d owe her too much…; in Misery of Love, the latter part is absent, creating the sense that Claire simply takes Alain at his word, evidently not understanding how this ‘favor’ would affect their dynamic as a couple.

Toward the end of Misery of Love, the pace of the fragmentation ramps up, obscuring the temporal anchor of the wake. In rapid succession, the cartoonist reveals that both Claire and Alain’s sister, Martine, were both sexually abused by their fathers, and that, while Claire wishes to discuss their shared trauma, Alain is visibly upset by the notion, evidently scared of what the father’s abuse says about the son; that Claire and Alain eventually do get married; and, most importantly, that Claire is already pregnant at the time of the wedding. When Alain absconds to Thailand, claiming the child — mixed race just like Alagbé himself, black to some yet white to others — is not his, Claire is left to care for her young daughter all alone (“It’s all right,” she tells her doctor after the latter tries to console her, and those three stoic words are perhaps the most devastating line in the whole book). The pace becomes so breakneck that one wonders, in fact, whether these events actually happen or Claire merely imagines them — after all, Alain did get arrested at the end of Yellow Negroes, an incident that Alagbé refuses to offer any resolution for.

Whether real or imaginary, the emotional realm remains the same: a sense of abandonment, as the past encroaches upon the present. Perhaps this is the misery of love: that it cannot exist on its own; that its surroundings will always eat away at it. And then? Then what are you left with?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply