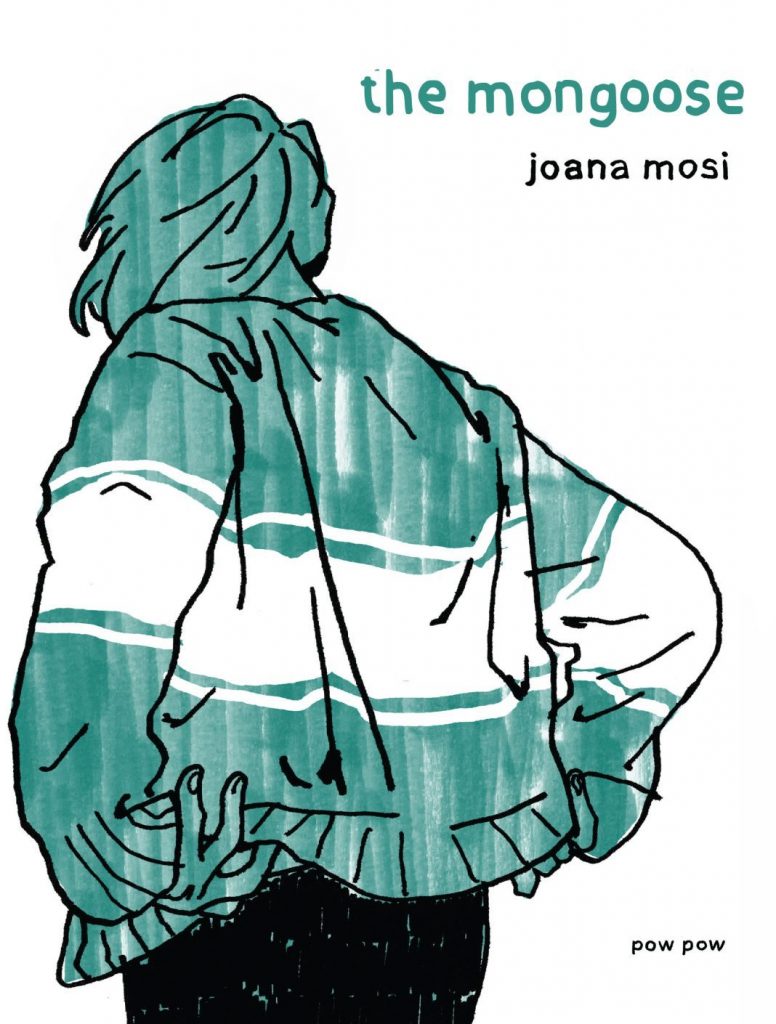

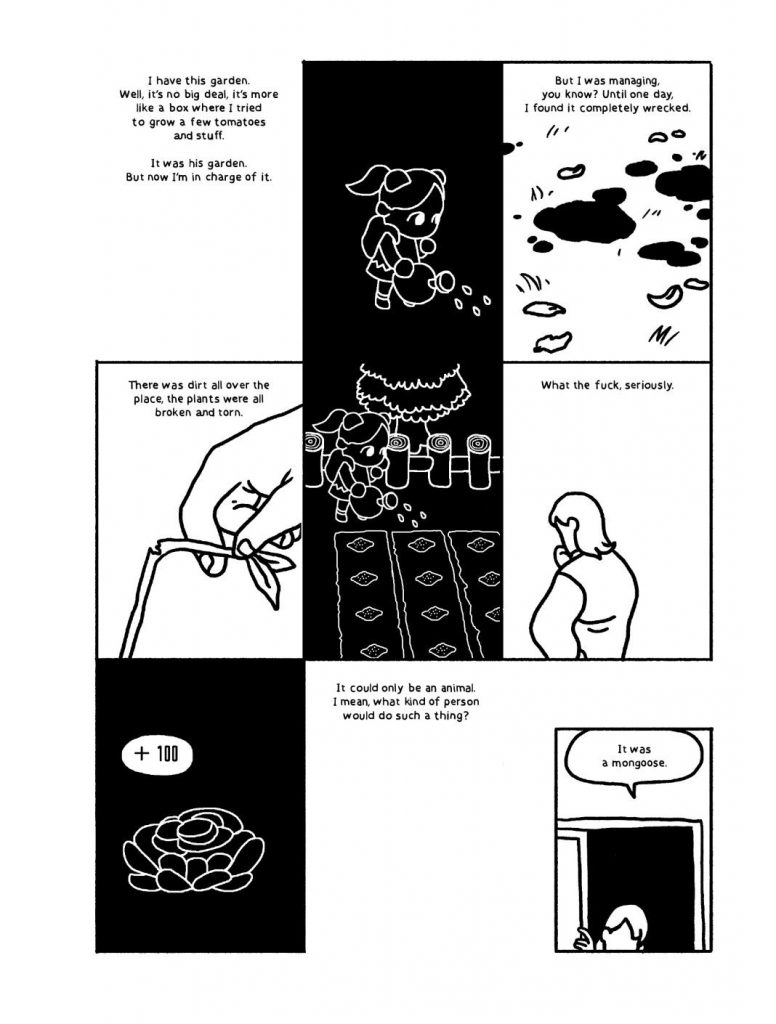

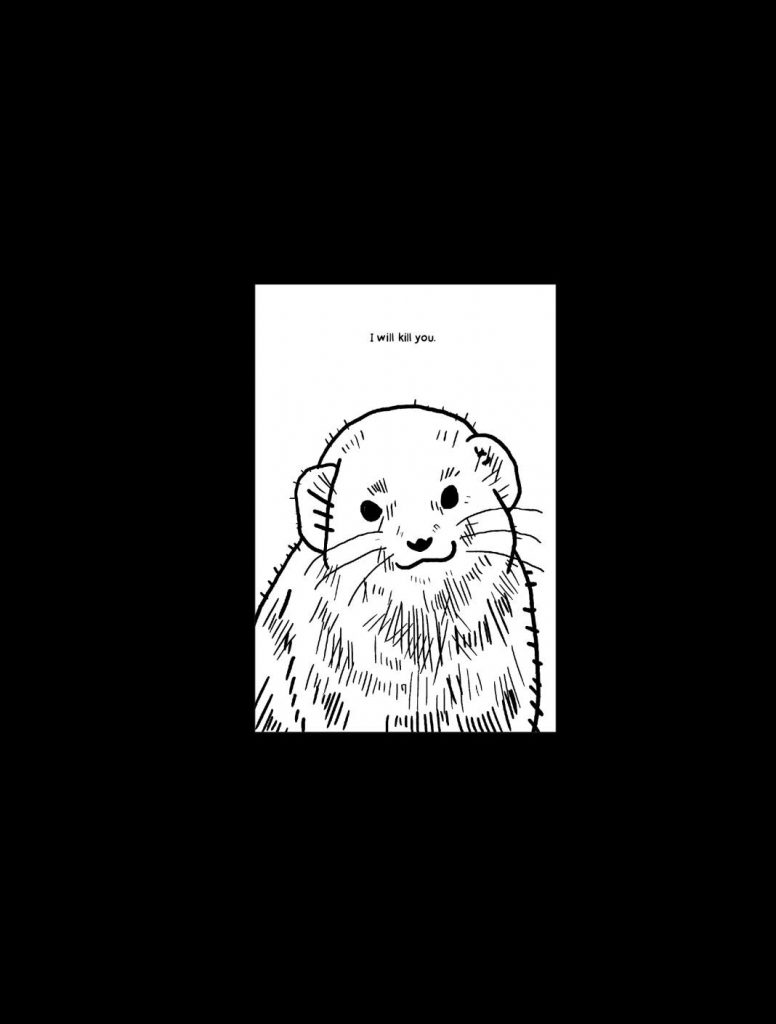

The premise of Joana Mosi’s most recent work sounds simple: Júlia is living in her grandmother’s house with Joey, her brother, and she becomes frustrated with a mongoose that has attacked the garden she started to grow. The problem is that nobody, including her, has seen the mongoose. In fact, nobody other than Júlia believes the mongoose exists, yet she can’t stop talking about it. It quickly becomes apparent that the mongoose is a stand-in for the death of her husband, Paulo, which she won’t talk about, and she is not coping with that loss well. The mongoose becomes a symbol for her grief, in that it consumes her thoughts, but it also becomes a replacement for that grief, in that she talks only about the mongoose, but not her suffering.

As in many instances in life, people around Júlia try to help her deal with her grief, but she is unable or unwilling to accept that assistance. One of her co-workers initially talks with her about the mongoose, but clearly doesn’t believe that it exists, suggesting it might be a cat that attacked the garden. Much later in the work, though, that co-worker has talked to one of their fellow teachers and found out about a trap that might work to deal with the mongoose. Even though Júlia hasn’t tried anything to actually deal with the mongoose—a symbol of how she hasn’t taken any steps to deal with her grief—she doesn’t accept her co-worker’s help.

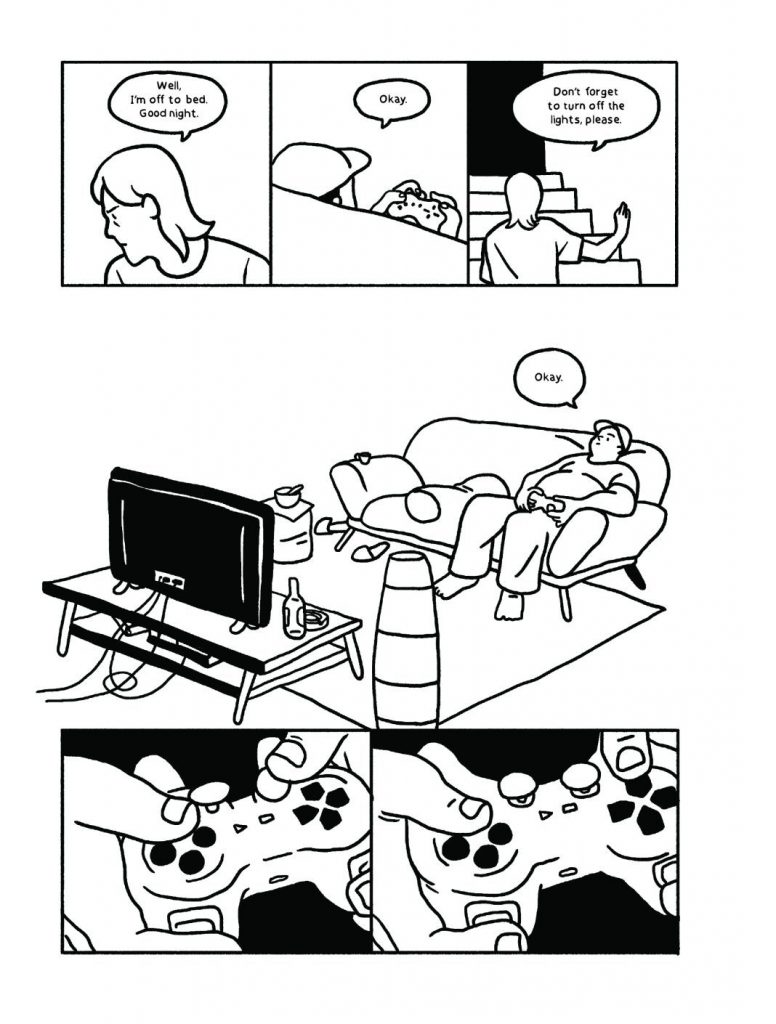

Similarly, her brother Joel tries to help her in a variety of ways. He’s moved in with her because he lost his job, but it also seems as if he’s there to try to help her deal with her loss. He makes her dinner one evening, which surprises Júlia, and he’s always checking to make sure she eats. Near the end of the work, he even begins replanting the garden with some basic vegetables, a symbol of how he’s trying to help her begin growing again, as well. He finds the time and energy to help her, even though he’s struggling to find a new job again. He has an interview with a company, where he talks about video game design he’s done before, and it’s clear he’s overqualified for the job, which focuses on addictive games for phones. Still, he’s taking action in the midst of his loss, a clear contrast with Júlia.

Their mother tries to help Júlia, but, as is often the case with family members, her attempts seem to do more harm than good. Given the mother’s affect, it’s understandable why. Rather than clearly hearing and understanding her daughter, she bulldozes through whatever Júlia says, believing she knows what’s best for her daughter. A small example is when she comes over for lunch, and she brings groceries, including bread. Júlia told her on the phone that she already had bread and, thus, didn’t need any. Leading up to the lunch, Mosi has two parallel sets of panels, one of Júlia running, while feeling like a mongoose is following her, a clear representation of how she feels stalked by grief, and the other of Júlia’s talking about her mother. Then, when her mother arrives, she speaks almost nonstop, moving from advice to chastisement: “You can freeze it [the extra bread]. It’s important to eat properly. Have you noticed those dark circles under your eyes? I’ll make lunch. You have to get your vitamins and nutrients and anti-oxidants. And fibre. Fibre is very important.” Not surprisingly, Júlia spends much of the work trying to avoid her mother, though it’s clear to the reader that her mother does actually care; she just doesn’t know how to deal with her daughter’s grief.

Near the end of the work, Júlia gives her mother a candle, which unleashes an honest confession about her grief. Most of the page shows images of Júlia crying, interspersed with pictures of a mongoose or her mother or Paulo, as Júlia admits to her mother, “Some days I forget about it, as if nothing ever happened. . . But then I remember, and feel everything all at once. . . I’m so sick of this. I’m so sick of it all. . . There has to be another way. . . I’m so exhausted, Mom.” It’s this confession that finally moves Júlia to take some sort of action.

Júlia finally agrees to visit a therapist to try to help her work through her grief, though she immediately denies that she’s depressed. When she talks to the therapist, she talks about the mongoose and the garden, nothing about Paulo until the therapist forces her to do so. However, it’s not as if Júlia attends one therapy session and everything begins to work out for her. She does, though, return to the memory of climbing rocks on the beach with Paulo, moving to the part of the memory where he says, “I’m not going anywhere,” which implies that Júlia is making progress in dealing with his loss.

Just after that memory, the artwork changes to a style Mosi has only used once in the work to this point. Throughout almost all of the work, she uses a simple black-and-white style that provides the bare details of a scene, leaving the reader to fill in the gaps. Unless Mosi is providing close-ups of faces, for example, the face often has no details, and the surrounding details in most scenes are suggestions of objects, at best. Mosi shifts, though, to a single panel per page, not even a full page, but only about ¼ of the page, centered, with scenes from Paulo’s life. Even though she leaves the faces largely blank, the scenery is much more detailed, as if Júlia is reliving these moments or looking at photographs of events in her and Paulo’s relationship. The captions, though, are facts about mongooses. It’s almost as if Júlia is describing her grief in detail, while remembering Paulo.

Mosi’s work is an apt description of the grieving process, as she doesn’t provide platitudes for healing, though some of the characters do. Instead, she reveals the ways in which we avoid facing the losses life gives us, as well as the ways in which we avoid the help that is right in front of us. The final description Júlia provides of mongooses is that they are born blind. The truth is that humans are, as well, at least metaphorically. We are unable to see the resources we have that can help us move forward through such suffering, unable to see the love that often surrounds us during such times. But we stumble through together and, occasionally, find one another when we need to.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply