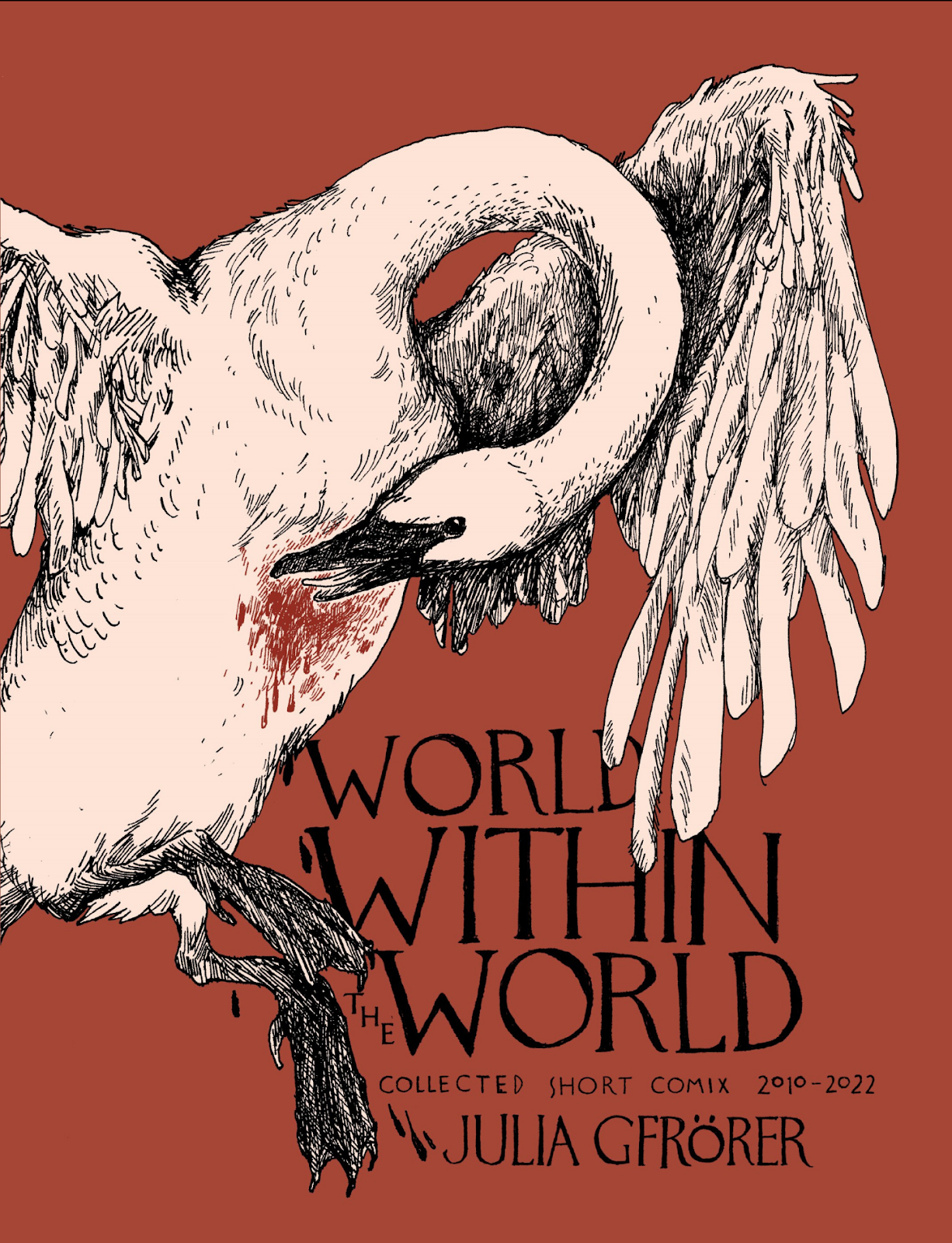

To read Julia Gfrörer’s comics is to feel her carving profane things on the inside of your skull. She is often described as a horror cartoonist, and to the extent that art needs a label in order to discuss it, this is more true than not. But such an appellation feels oddly non-specific, not quite able to capture the stomach-churning mix of unease and exhilaration I feel when looking at her linework. Her drawings manage to crawl under my skin and transport me to dark places I would rather not visit, but seem unable to leave.

The short, dense comics in Gfrörer’s World Within The World, published earlier this year by Fantagraphics, often explore the subterranean and forbidden. As the title suggests, this collection of stories and images is often concerned with interiors and enclosed spaces: prisons, coffins, deep pits, and anything else that lies beneath the surface of the world. The titular comic, a one-pager that opens the volume, features a conversation between Gfrörer and seventeenth-century Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, who warns her that “all rooms are dangerous.” This is undoubtedly true, at least within Gfrörer’s comics. Yet the hidden spaces scattered throughout this collection are also filled with insatiable desire, artistry, and twisted forms of beauty.

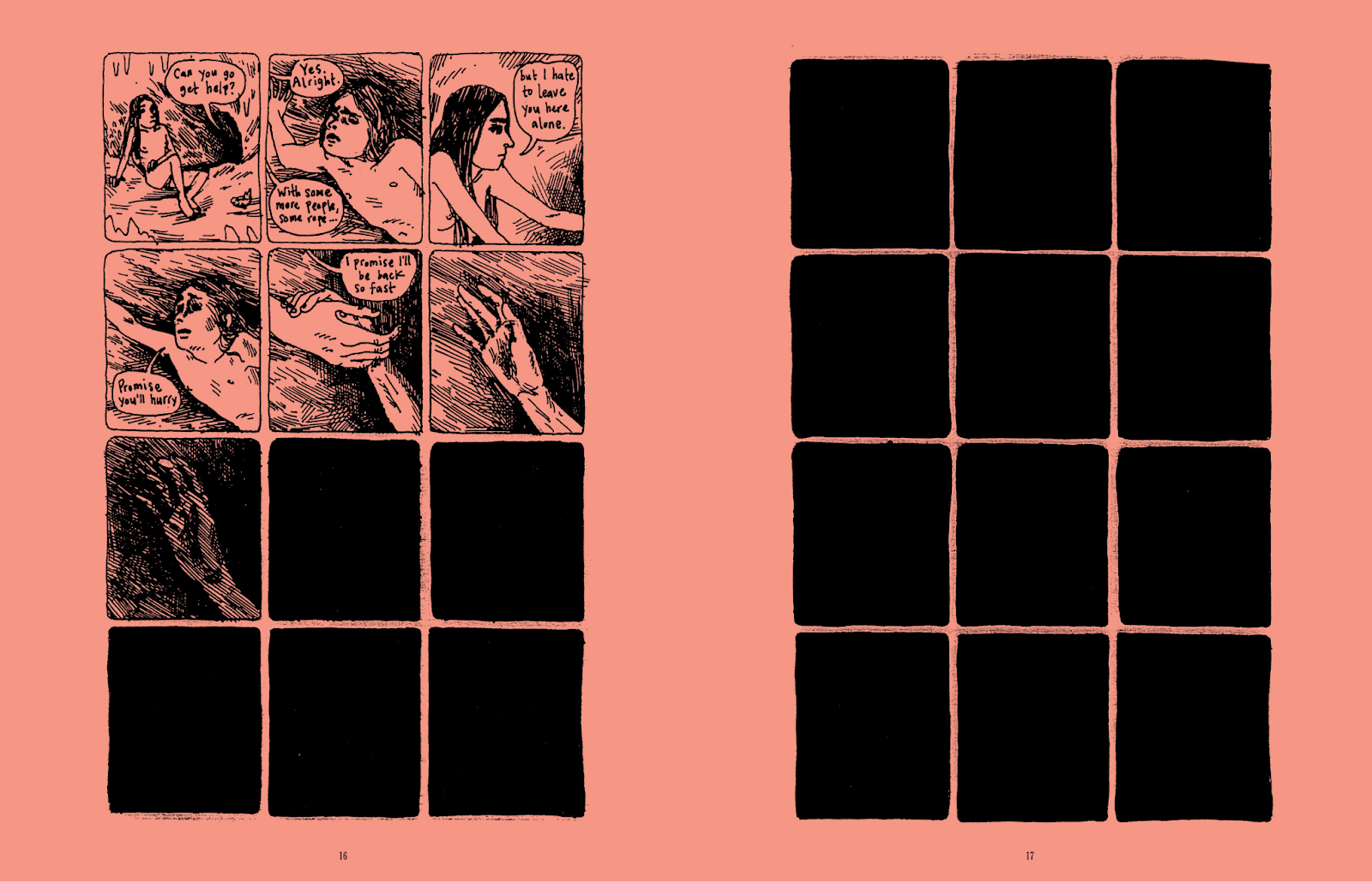

In “Dark Age,” the collection’s first extended comic, Gfrörer depicts premodern humans who wander into a beautiful crystal cave. It’s a site of awe and physical pleasure and creativity, all interwoven and mixed together. The two of them, a boy and a girl, have sex and gaze at jagged crystalline formations and ponder images of animals they previously scrawled on the walls — the oldest known form of art. But as they venture deeper into the cave, their carnal bliss unravels and pleasure melts into pain. The crystals cut their feet. The cave shrinks, becoming less easy to navigate, until finally the boy gets stuck trying to shinny into a passage too small for him. When the girl leaves to find help, she takes their torch with her, and Gfrörer illustrates the boy’s isolation with sixty-seven panels — over five full pages — of total blackness.

This is one of the book’s most metatextual moments. Here, the danger lurking at the heart of the world within the world reaches out and obliterates the comics page itself, turning each panel into an impenetrable void. Delving into the cave is necessary to make art, but the risk is potentially all-consuming. Perhaps annihilation — or, at the very least, overwhelming torment — is, for Gfrörer, the price of creation. Escape is not guaranteed, and even if you manage to find a way out, you will not be the same. The boy, for his part, reaches the cave mouth and is confronted by a demonic visitation, a figure only he can see: the fractured shadow of a man with antlers, standing between him and the sunlight. In the comic’s final panel, the shape beckons, but even as the boy flinches away, it seems to summon the reader onward through the cave mouth and, by extension, into the rest of Gfrörer’s book. We are thus invited to contemplate the things she has drawn on cave walls during her own journey through the dark places of the earth.

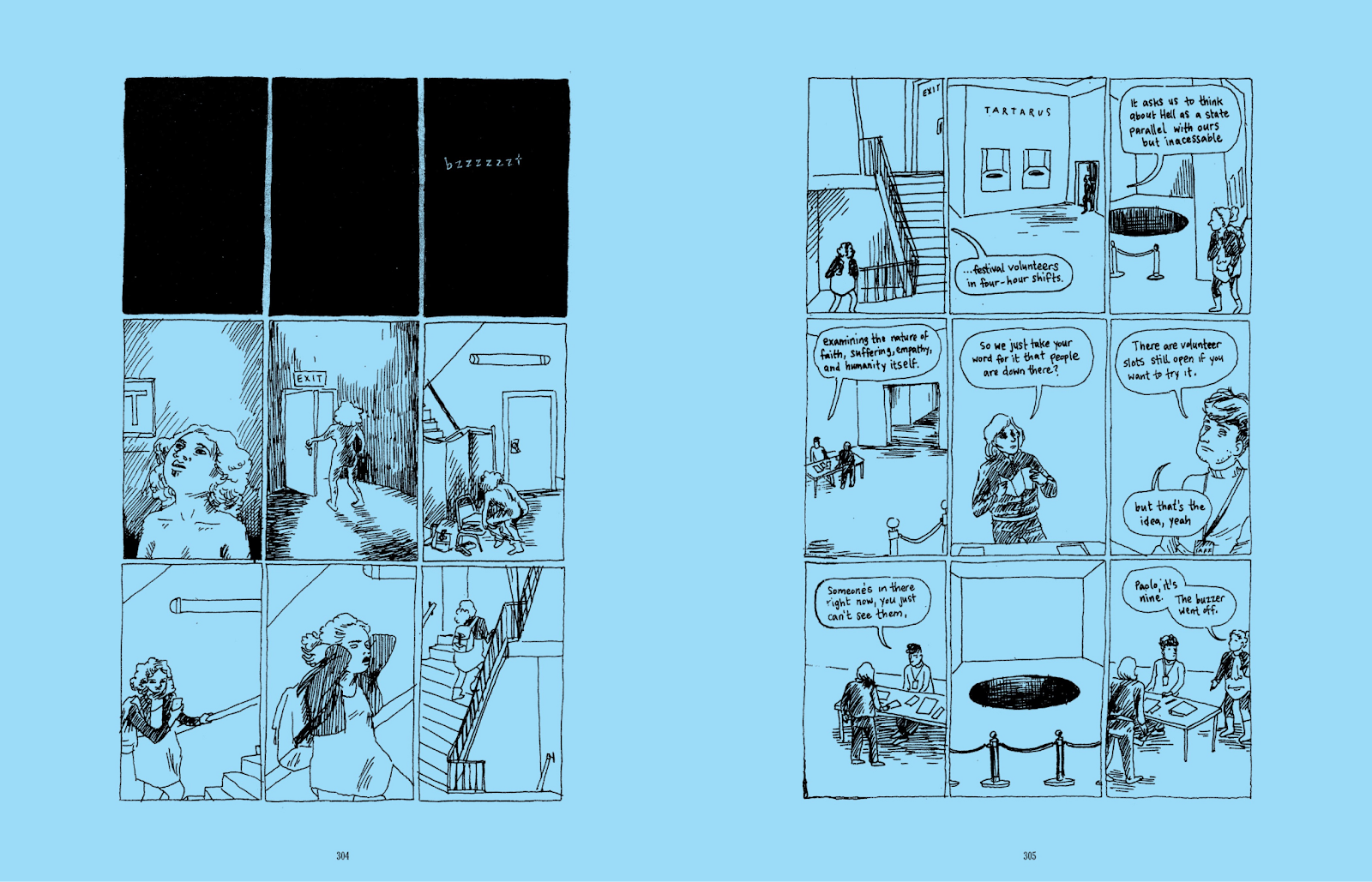

Consider also what Gfrörer has to show us in “Tartarus,” the book’s penultimate comic. This is another story about the relationship between artistic invention and a hole in the ground. While many of the images in World Within The World feel ripped from myth and ancient history, the book as a whole spans — roughly — all of human history, and “Tartarus” is a rare dispatch from the future (circa 2040). It centers on an artistic installation of the same name: a dark pit in a gallery that represents the simultaneous presence and inaccessibility of Hell, a parallel world you can sense but cannot access. The installation is continuously inhabited by volunteers who stand alone and naked at the bottom of the pit, and its artistic power is, in theory, sustained by belief: viewers just have to accept that someone is at the bottom, even if they can’t see them.

If “Dark Age” shows us the beginning of art, “Tartarus” previews its end. The pit was designed by an artificial intelligence program trained on artistic depictions of hell, and the human volunteers serving symbolically as the damned are all young artists who work with AI systems. This isn’t to say that the characters aren’t making art just because they are using new technologies; Gfrörer doesn’t explicitly pass judgment on this. But their creations seem as far removed from prehistoric cave drawings — and, frankly, from self-published zines, an artform Gfrörer passionately champions — as it is possible to be. The social world these artists inhabit is also structured by fancy grants and competitions, committees and annoying, all-white juries. Worse, their audiences are ignorant and careless. One woman takes it upon herself to test Tartarus by throwing a pencil into the pit and, in doing so, destroys the premise of the exhibit. This is a world in which art is created mostly for the wrong reasons and consumed by people who won’t understand it anyway. Not a cave crushing you to death but a form of oblivion nevertheless, and it feels appropriate that “Tartarus,” the comic, begins and ends with panels of absolute blackness.

In some ways, neither “Dark Age” nor “Tartarus” are fully representative of World Within The World. There is no necromancy or witchcraft in these two comics, nor any of the erotic horror and gruesome deaths that populate much of the book. But they still serve as artistic ciphers, keys to what the world within the world might actually be. In both, Gfrörer’s characters are trapped and naked in the dark; the only difference is that her artists of the future, stripped of prelapsarian illusions, clinging to their pretentions, choose to be alone in a prison of their own creation, sustained by their belief in the necessity of their craft. To delve beneath the surface of the world is to entrust yourself to that earthy darkness. You hope it will, perhaps, reveal the outline of something terrible and beautiful that you can carry back to the surface. But there is no guarantee it will survive in the sunlight.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply